Esther Kellner grew up learning about Hoosier folklore and early settlers in Indiana through stories passed down from her great-grandmother, an early Indiana school teacher. She published her first story when she was only eight years old. At age twenty she became editor of a children's magazine Play Mate. In 1956, she won the Indiana University Novel Award for The Promise, a biblical novel. She became involved with Wayne County Civilian Defense in 1965, later becoming the director while still publishing other fiction. Her nonfiction included accounts of pioneer life in Out of the Woods, moonshining in backcountry Southern Indiana and Kentucky in Moonshine: Its History and Folklore, and caring for small woodland creatures.

For more than twenty years, her home functioned as a nursery and refuge for injured, lost, and orphaned small animals, prompting her to write Animals Come to my House: A Story Guide to the Care of Small Wild Animals. Her interest in the environment is evident in her extensive knowledge and vivid descriptions of plants and animals.

Through stories passed down over the generations from her family and others Esther compiled Moonshine: Its History and Folklore. Though the main topic is moonshining in southern Indiana and Kentucky, the environment plays a large role in the ability of settlers to make and sell beer in secret once it became outlawed. She explains the importance of beer culturally, medically, and spiritually before bringing us to backcountry Indiana with its “high bluffs, deep hollows, steep wooded hillsides, and streams,” excellent settings for moonshining (30). The pioneers who settled here did not come without a treacherous journey but preferred the safest path on “Wilderness Road” along the Ohio River (49).

Once the government outlawed alcohol, backyard distilleries appeared all over the densely wooded hillsides, in undiscovered caves, and in other areas secluded by nature (56). The undisturbed environment also contributed to the freshness and taste of the alcohol produced. What made Bourbon characteristically unique and flavorful were the “oak storage barrels, charred while still green” (obviously native Indiana oak), and the spring water, used as an ingredient, from the large limestone shelf under Indiana (62).

In addition, nature provided security from the law enforcers who raided and destroyed such places of illegal activity. Part of growing up to Kellner meant observing nature and becoming aware of its presence all around, as the following passage illustrates:

As a child in the back-country I was taught very early in life to know the difference between the sound of a mother robin simply calling her young and hastily warning them, the difference between the “passing call” of a crow and his signal of danger or distress. There are many other wildlife warnings which revenue men found betraying and frustrating, among them the barking protests of a fox squirrel and the raucous resentment of a bluejay. Thus it was necessary for them to learn some of the tactics of surveillance, concealment, and surprise which had been the mountaineers’ means of survival for a hundred years. (84)

However, as time passed and local deputies became more aware of how they too could use nature to sneak up on their opponents, raids and killings occurred more frequently, and moonshining declined. She writes of the further destruction by human-kind when the highways paved over the tangled forests, and tourists trample through caves, the forgotten hiding places of the stills. Yet, the spirit of moonshining lingers on the overgrown moonlit paths and the old hickory fires, which used to burn in the hollows.

Unlike Moonshine, composed of tales told to her in the third-person, Out of the Woods is a narrative of Kellner’s own life growing up on the edge of the untamed woods and is her greatest work about Indiana’s environment. She describes this remote world, unknown to the town-and-city dwellers, though tainted by their ancestors of pioneer Indiana:

Pioneer Indiana was a dense wilderness, dark and damp and full of swamplands. The flowers that grew in the dimness and dampness could not live in the sun, and so vanished with the trees. Settlers brought new ones, sometimes on purpose, sometimes by accident. They packed their belongings in hay and straw from European fields, and the seeds of European plants became immigrants too, and flourished here with the families that fetched them in. (23)

Some of these non-native plant species included dandelions, bouncing Bet, Queen Anne’s lace, the common field daisy, and the yellowish-brown lily along country roadsides. The native plants not destroyed by invasive species are ironweed, pokeberry, the wild rose, and the rare cardinal flower (23). Even the Starling, a bird brought from Europe in 1890, is an invasive, introduced species. Though regarded by some as valuable for their diet of harmful insects, they are pests to others because they gather on buildings, soil sidewalks and walls, and twitter loudly and constantly (38).

She describes various native small animals, such as squirrels, raccoons, owls, red-tailed hawks, foxes, skunks, bats, and even insects and amphibians. She distinguishes in detail poisonous and native plants, fruits, and trees and accounts of children dying after blowing whistles made from hollow stems (156). She speaks of the poison in the following passage:

Indeed, in the woodlands of Indiana poison hangs over our heads, springs up at our feet, nudges our elbows. Poison threatens us in tender roots, lush and lovely leaves, beautiful flowers, and mellow fruits. It spreads along our country roads and creeks, across our summer meadowlands, over our forest floors, our swamps and hilltops. (155)

White snakeroot, otherwise know as “milk sickness,” is one such plant that grows prolifically in Indiana woods and damp valleys and which killed many settlers through infected cow’s milk and animals from eating it (78). She even points out a human introduced predator to small animals, the house cat, in this gruesome citation:

He is able to climb the highest trees and, with his merciless front claws, rake whole families of sleeping baby birds and animals out of their nests. Permitting house cats to roam and hunt at will has been responsible for the wanton and senseless destruction of much valuable wildlife.…Many cat lovers are almost unaware of this side of the animal’s nature, and have never experienced (as I have) anything like a cat chasing a small chipmunk and biting off its head at such speed that the bloody and decapitated chipmunk kept on running. (142)

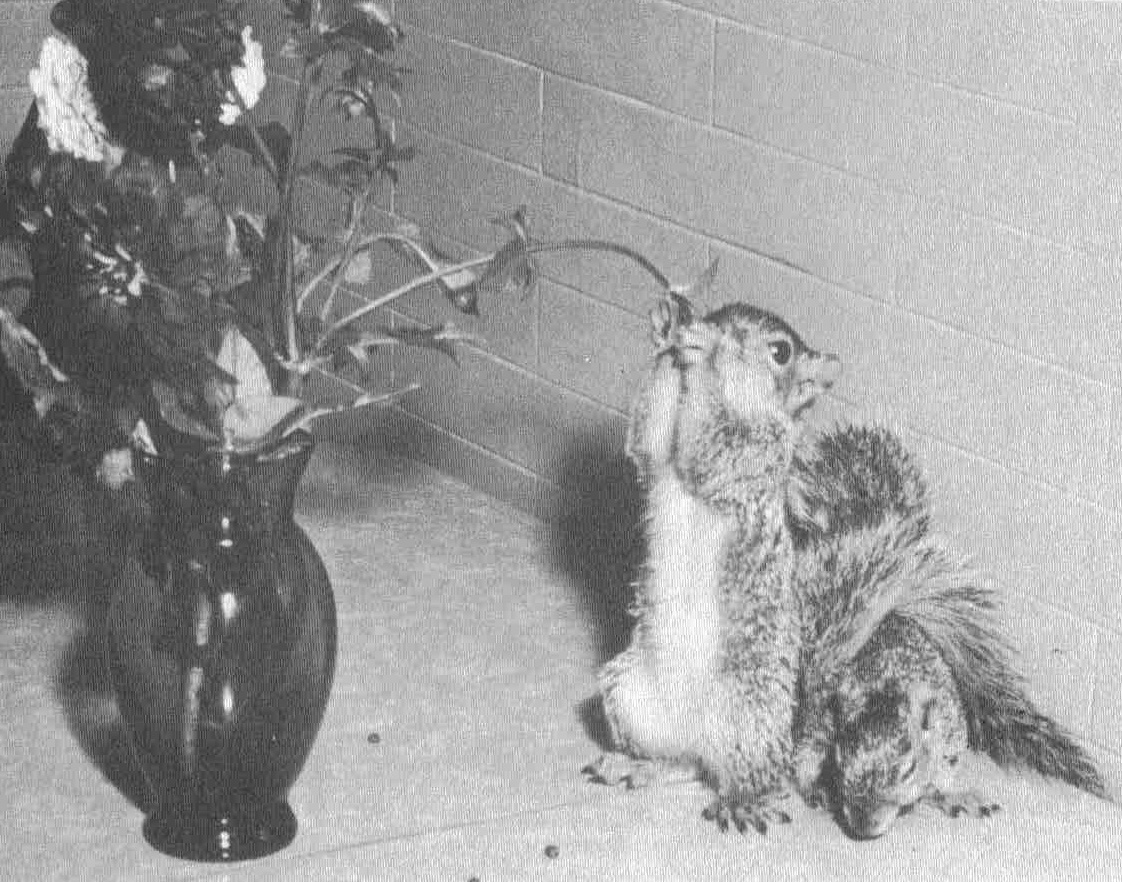

Although Kellner often tells of the destruction of animals and their habitats, she also writes of its unsurpassed beauty. She describes the singing of crickets, squirrels stuffing their mouths with ripe fruit, and the songs of the mourning doves, indigo buntings, yellow-throated meadow lark, and wild finches. A hunter named Bill once said to her, “No, there ain’t nothing that can beat the purtiness of nature.” (7)

She talks of her first experience saving baby squirrels, and since then has been dedicated to wildlife rehabilitation. She elaborates on these stories in this book and in Animals Come to my House: A Story Guide to the Care of Small Wild Animals. Through stories of her own and of her friends who have taken in injured, sick, or orphaned baby animals, she describes each animal’s natural habitat, diet, and behavior, and explains how to simulate a mother’s nurturing touch so that the animal can be released back into the environment. Though she’s kept squirrels as pets that could not survive on their own, she strongly advises against getting attached to these wild animals needing to be rescued and released. In the introduction, Kellner speaks of the importance of wildlife preservation in the following passage:

Man has disrupted the natural environment of so many plant and animals that we have a responsibility to see that wild creatures survive. Without them, the acorns that squirrels buried and forgot about would never grow into oak trees, many ecological cycles would be broken, and the earth would become a drab and less interesting place. (1)

Kellner merely hopes people will care enough about the beauty and significance of this balanced ecosystem to stand for its perpetuation and add to the rich folklore passed down through the generations. Aiding in the preservation of wildlife, vividly cataloguing hundreds of plants and animals in her accounts, and exposing her readers to the untold history of the underground moonshine business, she shows the impact humans have had on our Hoosier landscape.

Esther Kellner reaches out to those too ignorant of their rich heritage, blinded by the city pollution, and limited by block after block of corporately own businesses in every city, to appreciate our unique and disappearing natural environment. She will be remembered for her important literary contributions as a prolific Hoosier author as well as for her deep love for animals and nature.

--JMP

Sources:

“Esther A. Kellner.” Morrisson-Reeves Library, Richmond, Indiana. Oct. 17, 2005. <http://www.mrl.lib.in.us/history/biography/kellner.htm>.

Kellner, Esther. Animals come to my house; a story guide to the care of small wild animals. New York: Putnam, 1976.

---. Moonshine: its history and folklore. New York: Weathervane Books, 1971.

---. Out of the Woods. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964.

Images:

“Esther A. Kellner.” Morrisson-Reeves Library, Richmond, Indiana. Oct. 17, 2005. <http://www.mrl.lib.in.us/history/biography/kellner.htm>.

Kellner, Esther. Out of the Woods. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964.

Links:

Preservation and Conservation - Wildlife Rehabilitation

Native and Invasive Indiana Plant Species

Invasive Indiana Species

Indiana Poisonous Plants

|