‘I was going to use [drugs] until I was dead.’ County court officials treat criminals with substance abuse holistically.

By: Amanda Joerndt

YOUNGSTOWN, OHIO — The Mahoning County Common Pleas Drug Court in Northeast Ohio gives drug offenders who have committed drug-related crimes a chance to go through a holistic — physical, mental, social and emotional — transformation to recover from a lifelong journey of substance abuse.

Denise Raub, a 32-year-old Poland, Ohio resident, started using drugs as a teenager growing up in her small Ohio community. Situated in the suburbs of Youngstown, Ohio and minutes away from the Pennsylvania border, Poland is one of Mahoning counties 14 cities and villages.

Raub was introduced to prescription drugs around 16 years old after having several dental procedures where she was on heavy medications like Vicodin and Percocet quite often and made her feel “comfortable in her own skin”. She said this wasn’t the main reason she started using drugs, but these drugs introduced her to other hard substances down the road.

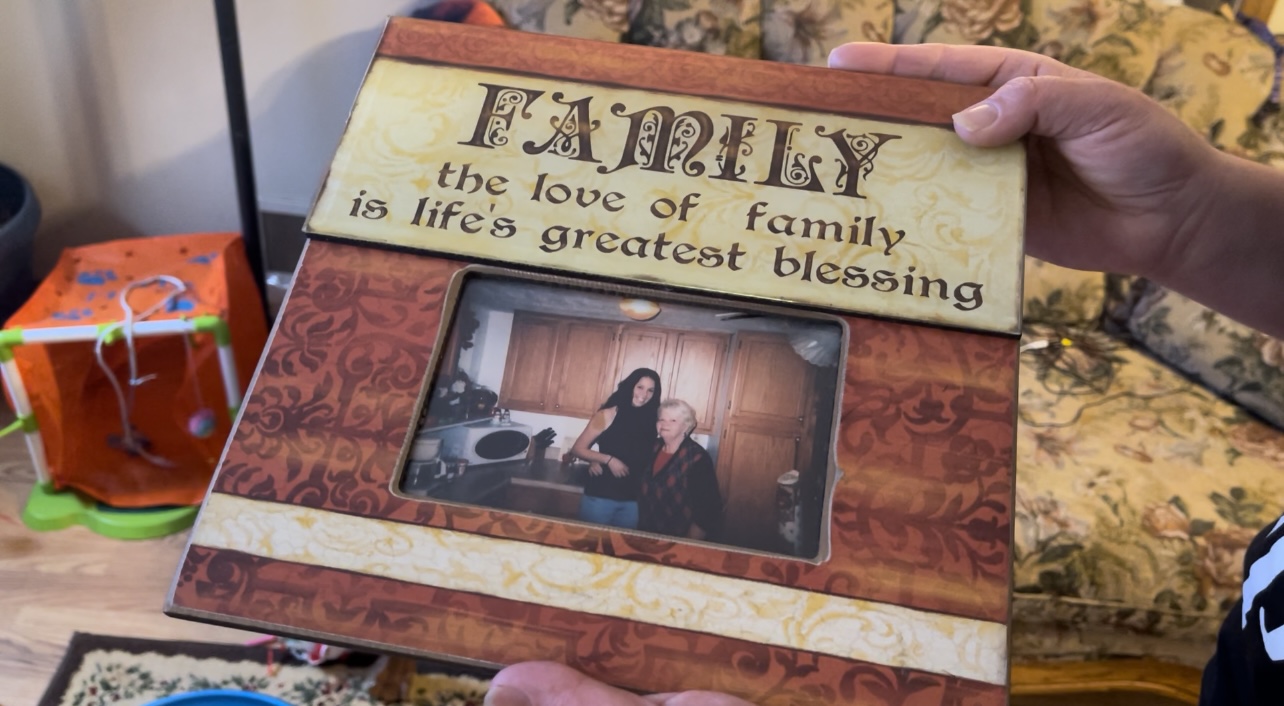

Raub was seven years clean when her grandmother passed away from COVID-19 in January 2021. She said she quit every “hard” substance, but was still drinking alcohol regularly and wasn’t taking healthy care of herself physically and mentally. The stress and loss of what was her only mother-figure in her life caused her to go back out on the streets to start using again after working toward a life of recovery for so long.

“I lost my mom and my dad is in recovery, so my grams was my mom, cheerleader, everything,” Raub said. “But God knew she needed to be removed so I could be independent, as much as I loved her to death.”

Raub said a normal day for her while on drugs was not knowing whether the sun was rising or setting. She would go days without eating and not even realize it.

“I remember being in total chaos and confusion, you don’t know where you are or what day it is,” she said. “Its almost paralyzing and you have to sit there and figure out what’s going on. After that, it’s only about that next drug and how to get more.”

Raub said this time around, she knew there was no going back to sobriety once she started using drugs again.

“I knew when I was out there that I was never going to stop now, I was going to [use drugs] until I was dead,” she said. “I fell asleep in a McDonald’s parking lot drive through with a bunch of meth and other substances. I [was charged] with three felony fours and one felony five for aggravated possession.”

Ohio felony levels are sorted into five categories: a first-degree-felony is the most severe with three to 11 years in prison and a maximum of $20,000 in fines, according to the Spaulding & Kitzler attorney group. A fifth-degree-felony is the least severe with six to 12 months in prison and a $2,500 maximum in fines. Third-degree felonies in Ohio include fleeing and eluding and certain drug offenses.

Individuals who have been charged with fourth or fifth degree felonies and have non-violent, sex or weapon related charges are eligible. There also must be evidence of a drug addiction.

When the drug court program was presented to Raub by her public defender when she got arrested in March 2021, she said everyone was telling her the program would set her up for failure and she would be “signing her life away and still end up in prison.”

But Raub said it’s done the complete opposite for her.

“Both of my parents [were] addicted and my father was very abusive physically and mentally with my mother,” she said. “They split up when I was six or seven. I saw a lot of things when I was little, like manipulation, and I noticed looking back that I portrayed all my [trauma] symptoms as an addict.”

Raub said being a part of the drug court program holds her to a much higher level of accountability that she’s never had before while recovery from drug use. That makes this time around living a sober lifestyle a different experience, she said.

Now she doesn’t dread waking up in the morning and stopped “praying to die while in her sleep,” Raub said. She gets to look forward to what the next day holds for her.

“I’m almost back to being a morning person. I never in my life have been on a routine like I am now. I get up early, make my coffee, shower and play with my cat,” she said. “I go to work, come home for lunch during work and get off at about 4:30. I do homework some nights or go to a [drug] meeting.”

She is now living a more independent lifestyle with her 13-year-old cat without having to rely on anyone to support her lifestyle like in the past. She works a full-time job at Polaris Windows and Doors and attends Kent State University working toward an accounting degree.

“Now I’m doing it, like I have my own place, I’m paying my own bills and not with any man,” Raub said, adding her long-term dream would be to build and run a sober living house on her family’s farm land property.

Like Raub, Leila Rood’s treatment in the drug court program has helped her realize her full potential as a young adult without a life of substance use.

Rood is 20 years old from Salem, Ohio, a small city in Columbiana County with nearly 12,000 residents, according to 2020 U.S. Census Bureau data. The city of Salem was founded by a Pennsylvania potter and a New Jersey clockmaker as the early settlers in 1806. Many homes in Salem served as stations for the American Underground Railroad until the mid 1800s, according to CityTownInfo.

Columbiana is a neighboring county of Mahoning and the drug court often admits residents who are eligible from regional counties into the program.

Rood was charged with three felonies and two misdemeanor drug offense charges for stealing from her grandmother while using drugs in December 2020, she said. Rood said she grew up in a household with substance use, which led her to starting down her own path of drug use.

“I was on all types of opioids, heroin and cocaine,” she said. “I was in and out of drug houses, running from cops, not speaking to family, dropping out of school and stealing.”

The Columbiana County Mental Health and Recovery Board Services reported in 2019 that parental use of drugs was an issue frequently identified in the county, along with a lack of parental supervision and exposure to drugs and alcohol.

Initially, Rood said she wanted no part of the drug court program, until she was told she was facing six years in prison for her drug offense charges. Rood knew she needed this program to turn her life around and make something of herself without a life of substance use.

“Since I’ve been in this program, I’ve learned how to become an adult, how to do day-to-day things in life, how to treat people and love myself,” she said.

The county’s felony-level drug court program became a specialized docket — a court that offers a therapeutic and judicial approach to provide treatment to individuals with substance abuse disorders— through the Supreme Court of Ohio in 1997.

Drug offenders have to plead guilty to their drug-related charges to be admitted into the program. Once they successfully complete the three phases of the program and are living an evident life of recovery, all of their charges are dropped.

The Ohio Substance Abuse Monitoring Network reported high usage of drugs in the Youngstown region — made up of Mahoning, Trumbull, Columbiana, Ashtabula and Jefferson counties — from June 2019 to January 2020.

Drug offenses involving heroin started to increase substantially in 2011. Nearly 125% of drug offenses involve heroin use, while non-heroin, opiate-related incidents decreased by 3.5% in Ohio, the Office of Criminal Justice Services reported.

Heroin use has been primarily used by young adults 18 to 25 years old, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Amy Klumpp, Mahoning County’s felony drug court coordinator, said when she started working for the court in 2005, she noticed marijuana wasn’t the gateway drug anymore.

“We were waiting for meth, but all of the sudden we got heroin addicts coming in,” she said. “They were upper to middle-class suburban kids. Eight kids from Springfield, six kids from Poland.”

Klumpp said the drug court is well aware of racial diversity issues with low representation from the African American and Hispanic communities. She said local and national drug courts do not see an equitable number of Black individuals.

She believes since the drug court does not have a public defender to bring in different groups of people for treatment, local attorneys are usually the court’s gatekeepers for eligible offenders and “do a lot of protecting on who would be successful or not.”

“We have the eligibility requirement of no weapons charges or convictions, which is very tough for young African American men because they’re often picked up on weapons.” she said. “We even talked about it recently and our prosecutor took it back to the office and they are not budging on that.”

Klumpp said more African American males have drug offense charges along with a weapon or violence-related charge because they are using weapons to protect themselves.The Mahoning County Drug Court has helped treat drug use and recovery for less than 10% of the African American community, Klumpp said.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People reported that African Americans and White individuals use drugs at similar rates, but the imprisonment rate of African Americans for drug charges is almost six times that of White persons.

Klumpp believes Youngstown may be more segregated between White and Black communities as to how they handle treatment and recovery compared to more “up and coming cities” like Columbus having more of a diverse drug offender population in the court.

“We’ve had very few Hispanics, and I think that the reason is versus going to a system, they go culturally to family or church. … They go within their own community to address issues.” she said. “I think it’s trust in the system.”

Many African American individuals are directed toward the Intervention in Lieu of Conviction program the county offers because attorneys believe it would be easier for them to complete it, Klumpp said. But she believes it’s not as effective and doesn’t hold the same level of accountability as the drug court does.

“We have two young men that probably are coming our way because they ended up with [one of the team members] who are young African American guys and they were immediately put in ILC,” she said.

Klumpp said when heroin started to be the patterned gateway drug most noticed throughout the program, the drug court team started seeing the children of judges, police officers, banks and more of an upper-to-middle class residency having substance use issues.

“In the days of crack cocaine, it was very punitive. In the days of heroin. … It was an interesting cultural dynamic,” she said. “Suddenly everyone was wanting to be more treatment-oriented instead of [sending drug offenders] to jail.”

One major change that has evolved over time is putting the right legislation in place for drug offenders who are successful, and not successful, in the program, Klumpp said. The court-appointed program used to be very criminal justice oriented instead of offering support, treatment and programming like it does now, Klumpp said.

“The issue is legislation, and it has changed so much,” she said. “When the court started in 1997, a felony level five could go to prison. It’s hard to get someone into prison [now] on a felony five, especially a nonviolent one.”

Klumpp said the drug court now offers more support and less punishment for drug offenders compared to 25 years ago.

“They used to come in and would have a whole number of cuffs sitting on the front and people would go to prison if they didn’t finish the program,” she said.

Klumpp added she has seen more drug offenders live a life of recovery and complete the program with a trauma-informed and holistic approach compared to a criminally-oriented approach over the years.

“We have a whole lot of different options in the county to divert them from going to prison,” she said. “I think that we have a great team and because of who the judge is and how long he’s been doing this, he’s well respected. Agencies are stepping over each other trying to get on the team.”

There are more than 64,000 drug offenders in federal prison, which is about 45% of inmates, and is updated on a monthly basis in the Federal Bureau of Prisons database. In Ohio, there were 42,900, nearly 29%, drug offense arrests made in 2018, according to a state Uniform Crime Report.

Karlee Briceland, drug court case manager, said placing criminals with substance use disorders in prison is not helping treat the problem of addiction, but fueling the drug addiction to continue to commit drug-related crimes after getting out of prison.

“If you put them in prison, they will stop using while in prison, but they haven’t gained the coping skills and support they need to live a different lifestyle,” she said. “When they come out, they will continue to do the same things or even worse because now they are bitter about being put in prison.”

Raub said going to prison would have just hardened her mindset and she would have not gotten the right help needed to treat the real problem.

“It would have just made me mad, resentful and angry and I’m not getting any type of help [for drug addiction],” she said.

Youngstown’s Municipal Court Judge Carla Baldwin said the historic structure of the legal system was built on looking at each person as a case number, and can hinder the opportunity for criminals with drug addiction problems to get the right treatment.

“It’s not a one-size-fits-all [system],” Baldwin said. “We’ve tried that and the booming number of our prison population in our criminal justice system shows us that’s not working, so we are compelled to do something different.”

Klumpp said one guy in the drug court program right now has several drug offenses against him and could potentially face several consequences. He has been through treatment several times and completed the program just to find himself re-entering the program for the same charges, she said.

“He’s never been successful, but I’m hoping at some point he’s here long enough to get it and quit playing the game,” Klumpp said.

She said incompletion of the program is rarely because of drug use. It’s usually a non-compliance issue with treatment in the program and the drug court team runs out of treatment options for them, Klumpp said.

“Over half of our clients [finish the program],” she said. “For those who don’t, they are sentenced and because of the rules in the legislation, for the most part, they end up in community control.”

Community control requires a person be supervised by a probation officer for a set period of time as required by the court, according to the Ohio Laws and Administrative Rules.

By placing drug offenders on community control, this can give them the opportunity to still receive some form of drug rehab or treatment in their sentencing by the court to treat their drug addiction instead of going to prison.

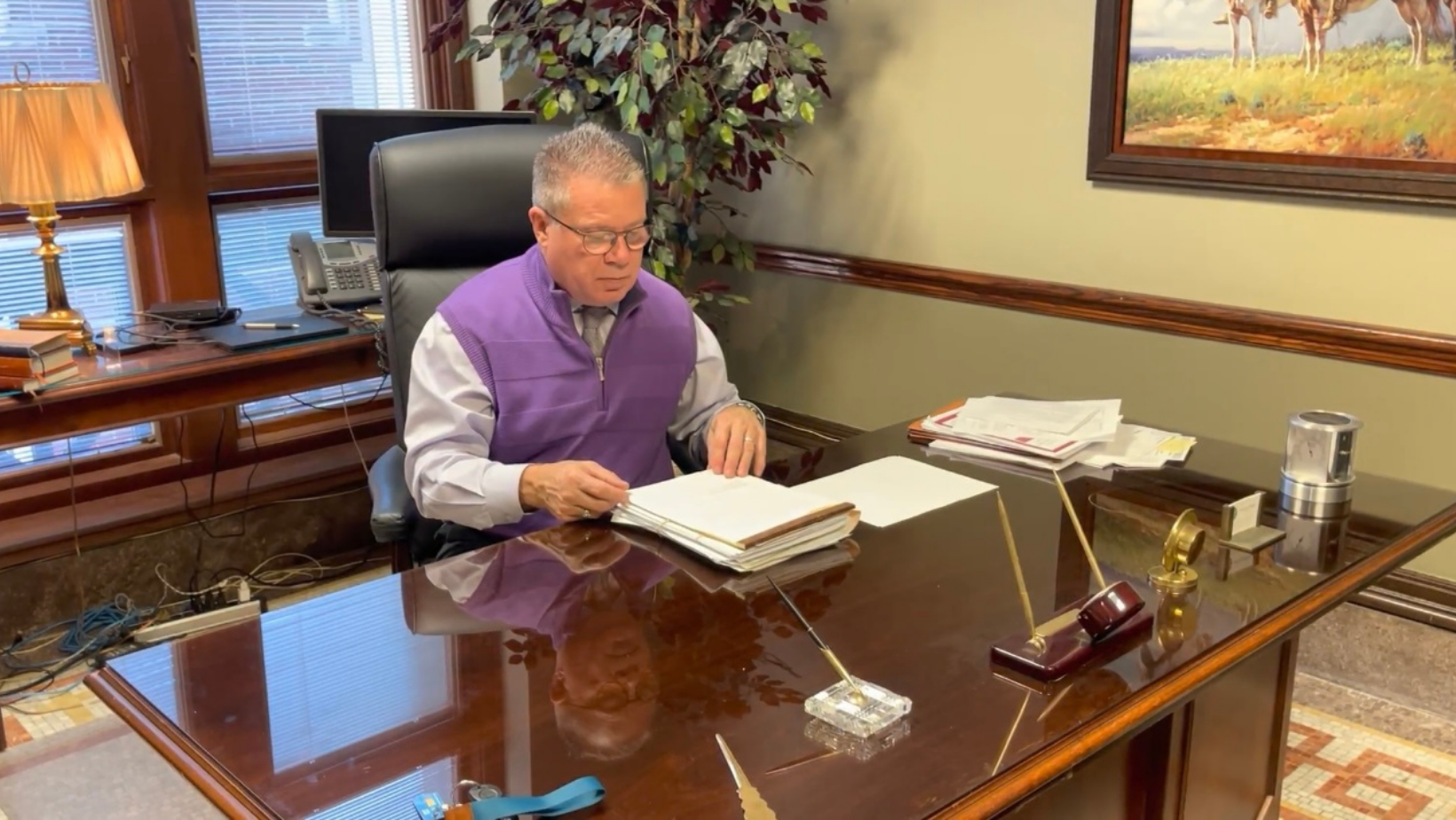

Another major impact on the county’s drug court program is having a judge that desires to form a relationship with each drug offender, like Mahoning County Common Pleas Drug Court Judge Durkin.

Judge Durkin is the longest running original drug court judge in Ohio, Klumpp said, which has made a lasting impact on drug offenders feeling respected and treated fairly while in the program.

“It’s like coming to see their dad. … He listens to them,” she said. “He makes it [a priority] and has a gift to recognize different things and get to know them.”

Judge Durkin said when he took the bench in 1996, his main promise to the voters was to establish a drug court in the county to reduce the high amount of drug use in the region.

“I was able to put the key stakeholders in place to establish what would be the second drug court in Ohio [at the time],” Durkin said. “We now have well over 100 [in Ohio], and it has been the best part of my job. The more I learned about it, the more I realized that this program could benefit the people of Mahoning County.”

There have been over 200 successful graduates of the program, and only 10% of the graduates have been charged with a new criminal offense, according to the Mahoning County Common Pleas Drug Court website. The national recidivism rate for drug court is over 30%.

Ohio counties like Hamilton and Montgomery have a recidivism rate three times higher than Mahoning County, according to a Hamilton County Drug Court report and an Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction report.

How past and present trauma play a role in drug crime victimization

Drug offenders who have been victims of circumstance are more likely to get involved in drug use, crime, violent and non-violent behaviors at a much younger age and continue this lifestyle into adulthood, Durkin and Klumpp said.

A victim of circumstance is defined as an individual who is impaired to make a rational decision and does not have the right balance of judgment needed to make the right decision, according to proceedings from the British Academy’s Maccabaean Lectures in Jurisprudence.

People’s lifestyle circumstances can result in limiting their range of choice and are put under a certain amount of pressure to make the wrong decisions, according to the report. While the jurisprudence lecture says this is not an excuse for wrong decision making and victims of circumstance should still be held responsible, being able to view the person in a holistic perspective and take their circumstances into consideration will help view the behavior in everyday life and the law.

Rood said both of her parents are drug addicts, which gave her the opportunity to “put her own spin” on her drug addiction seeing it first-hand from her parents, especially when her grandfather passed away in 2009.

“I’ve worked through so much [trauma],” Rood said. “I’ve been able to grieve properly for people that I have lost, and I’ve been able to work through [past] abuse to let people love me again.”

More than 26% of respondents who reported using alcohol, cannabis and cocaine in a 12-month period also reported committing a violent crime in the same time frame, according to the American Addiction Centers and the U.S. Department of Justice Drugs and Crime data.

Many drug offenders commit robbery and theft crimes to steal money or other material objects to buy more drugs, the addiction centers reported.

Almost all drug offenders in the specialized court program have experienced victimization through circumstances beyond their control that have led them to substance use, Durkin said.

Many drug offenders in the program are dealing with extensive trauma through being victims of circumstance in a romantic or family-involved relationship that is associated with substance abuse and “are trapped in the circumstances that are created by their choice,” Durkin said.

“Those who are with someone who’s making a lot of money, they are attracted to the lifestyle, money, cars, clothes and attention, and with that most of the time comes drug use,” he said.

Durkin said when a drug offender comes before the court in a family-related situation beyond their control that caused them to make wrong decisions — like being a victim of circumstance — he uses that as motivation to craft the right criminal sentence for them.

“[The charge] might be straight probation with community control, counseling or a combination of jail and treatment,” he said. “I cannot say the charge itself would be impacted depending on whether they are a victim because oftentimes it’s up to the prosecutor to determine what case is indicted.”

Raub said her mother passed away when she was 14 years old and she tried to commit suicide when she was 17 years old. Her disease has been around long before she picked up a drug, she said.

“I see my past insecurities, all of the things that made me not feel good like if I wasn’t selected or thought of first. I would react internally and from a very young age I needed to fit in and feel accepted,” she said. “The way to do that was to be a part of the one crowd that accepts anyone.”

Raub said her and her father have continued to work through their past traumas both having severe drug dependency issues and their relationship is “better than ever today.”

“I tell him everything now, and when I was a kid, I exaggerated, and lied, but today I don’t have to do that and try to remember what I told him last week,” she said. “The bond I have with him now is so amazing.”

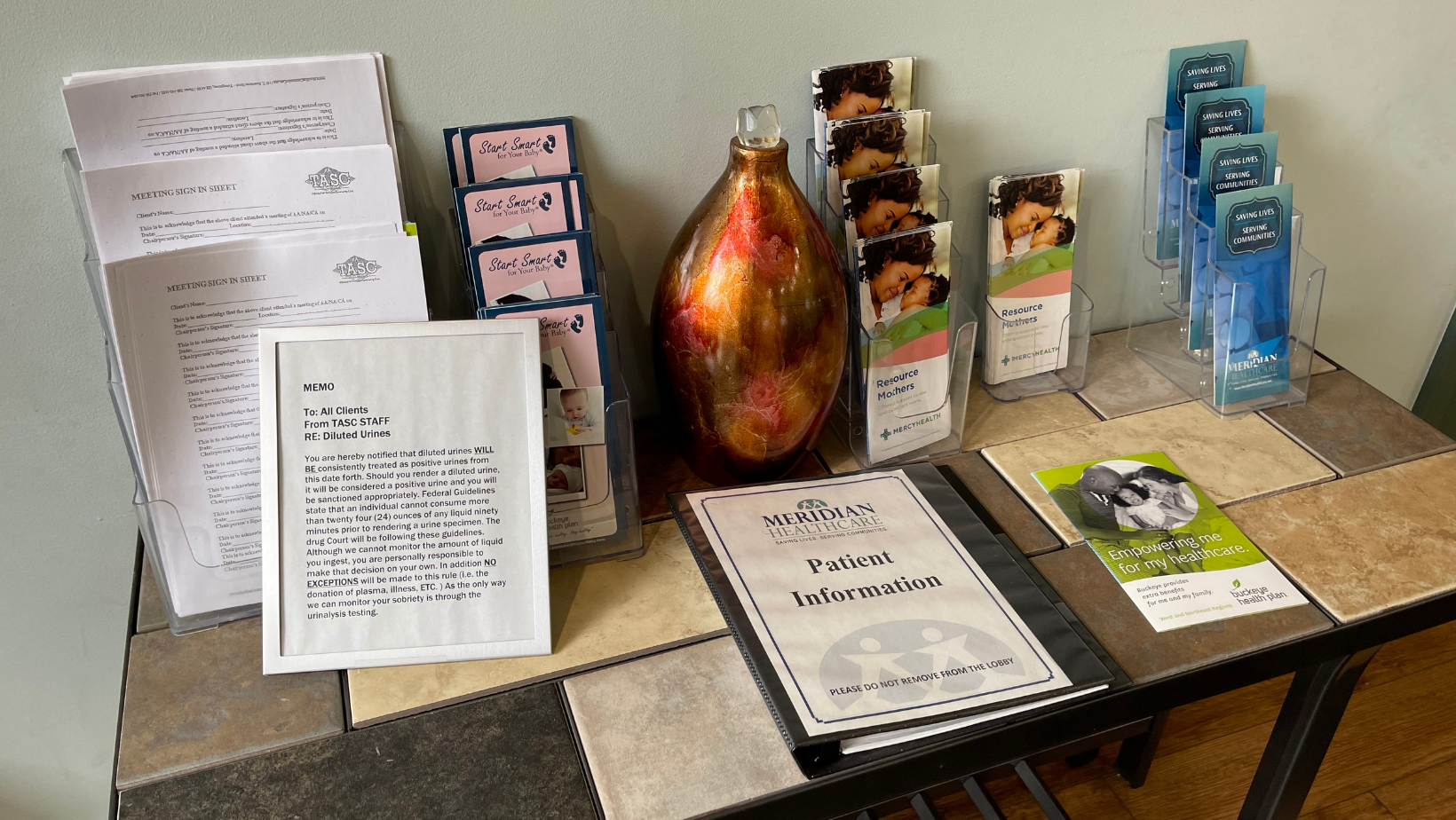

Karlee Briceland works for Treatment Accountability for Safer Communities — also known as TASC — which is a division of Meridian HealthCare in Youngstown that provides drug treatment, screenings and relapse prevention programs for drug offenders in drug court.

“Substance [use] is one of their biggest coping skills to deal with trauma and pain whether it was abuse, neglect, turning to substances is one way to [deal with] those things,” Briceland said.

While drug offenders are making their own criminal choices, their decision-making skills are almost always impaired by substance use — making it difficult to escape their circumstances.

“I would say it is next to impossible for people to make rational decisions when they are using drugs, especially depending on the substance,” Briceland said. “If someone isn’t in the right frame of mind, of course crime is bound to happen because you’re not who you normally are.”

Briceland said drug offenders in the program can continue to face traumas while in the program, which can cause them to relapse from being in the traumatic circumstances.

“We do have somebody in the drug court right now who graduated, lived a life of recovery for a while and then returned to substance use,” she said. “As much support as the drug court gives to people, they must put in that work and it’s not easy.”

The U.S. Department of Justice released an archived National Victim Assistance Academy report from 2000 that indicated a large percentage of people who commit crimes have drug or alcohol dependency issues.

More than 63% of adolescent victims said that their first use of “hard drugs” occurred after the year they were victims of assault or abuse, according to the report.

The agency found that many violence victims had post-traumatic stress disorder and substance use, abuse and dependence problems, the reported stated. Victimization is an important pathway to understand how substance abuse and delinquency are connected.

Mental health treatment programs for victims of circumstance help prevent future substance use disorders and criminal behavior. There is a need for victim assistance and support as a community-wide priority from government and private sectors, according to the report.

The county drug court addresses mental health and trauma-related victimization as a way to bring a holistic and supportive approach to their treatment plans.

“I think of a lot of our girls with their substance use disorder where they end up in relationships where they are very dependent,” Klumpp said. “We had a girl where both of her parents were heroin addicts, she started shooting them up when she was 8 years old and started using heroin herself when she was 12 or 14 years old.”

‘We go wherever the evidence leads us.’ How investigators and legal experts convict drug crime

A notably high number of violent crimes that are investigated in Youngstown have a connection to drugs, according to Youngstown Police Department Capt. Jason Simon.

The drug crime rate in Ohio increased by 58.5% between 2004 and 2014, the Office of Criminal Justice Services reported. This was driven by a 57.8% increase in drug possession offenses.

“There’s a high percentage of [violent crimes] that are linked to narcotics in this area,” Simon said. “There’s not a way to 100% prove that, but we do know that victim ‘A’ was a drug dealer.”

When a person is arrested by law enforcement on the street, they are brought into the detective’s unit to be investigated. When victims are brought in for questioning, Simon said investigators normally work up victimology — the relationship and interactions between the victims and suspects — to gather all evidence that is related to the incident.

“We [investigate] their background, family relationships, support systems. … That’s important to us,” he said. “There are suspects in cases where they commit an act of violence, but it’s like a defensive act because of the situation that they’re in.”

The simple answer to how investigators handle [drug] crime: Investigators will go “wherever the evidence leads them,” Simon said.

“There are always two sides to every story, and we want to know what those sides are. … Everyone has a reason for what they do,” he said. “There are cases where someone will say ‘Yeah, he owed me drug money and I killed them,’ or ‘I’m stealing all of this money to feed my drug habit.”

When officers are making arrests on the street, they normally have very little information on what happened and cannot make any assumptions on whether a person is a victim or not. This is where Simon works with the victims, suspects, witnesses and police to gather evidence and additional information to come to a resolution on each case.

Simon said when investigators are handling cases with victims of circumstance committing a drug-related crime for self-defense purposes, they look for affirmative defenses from victims to rely on when they are in court.

An affirmative defense introduces evidence — if found to be credible, will negate criminal liability or civil liability — even if it can be proven that the defendant committed criminal acts, according to the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

“They still committed the crime and it still happened, but they have an affirmative defense which is a legal avenue for them,” Simon said. “They [could] have a way legally to get out of their crime.”

Simon said if a victim or suspect needs additional community resources to steer away from a life of crime, investigators will do everything they can to help that person toward recovery. He said the investigators unit can work with court-appointed programs — like the Mahoning County Common Pleas Drug Court — to provide employment, housing, educational and general life resources.

“If we can try and get these people a high school degree or employment, generally this keeps them out of a life of crime, but they must want that,” he said. “Usually, it’ll be a breaking point that they come to, and they realize they need this in their life, or they are done for.”

Raub said when she would have an encounter with law enforcement or investigators after being arrested for drug use or possession in the past, they knew she was not a bad person or a hard criminal because of her drug addiction.

“It wasn’t about punishing me, they just wanted me to get some help,” she said.

On the contrary, Rood said she never felt heard or respected when talking with investigators to tell her side of the story, but realized she was ultimately at fault for her crime.

“I was always the bad guy, which I kind of was, but they never took my side into consideration,” she said. “I was always wrong for what I did.”

But now if Rood gets pulled over by police or encounters law enforcement today, she doesn’t feel as nervous or scared since going through treatment, she said.

“When I was using, I would run [from the police],” she said. “Today, If I get pulled over, I’m not terrified.”

Prosecutors in the Youngstown region work closely with suspects and victims of circumstance to determine the appropriate charge for drug-related offenses and find credible evidence related to the crime.

Martin Desmond, a prosecutor in Youngstown, has been working with drug-related cases in the region for years and started his own private practice in 2017. The drug distribution business is more complex than most people think, Desmond said.

“There’s a huge network of all these individuals who may not even know each other, but they’re in some way, shape, or form working together,” he said. “A lot of people think it’s just guys standing on the corner but it’s a whole process of manufacturing it, bringing it into the country and distributing it throughout the different cities.”

Desmond said when a prosecutor is looking to see if someone is going to be cooperative or not, it comes down to whether they’re willing to accept responsibility for their crime or remain not compliant with their criminal activity.

“Some people accept responsibility because they’re looking to get a better deal and get out of trouble, and other people do cooperate because they have some remorse for what they did,” he said.

Desmond said juveniles and younger kids who come from troubled homes, have a parent missing from the home or don’t have anything to latch onto for support can gravitate toward [a drug-related] type of lifestyle.

While this is not always the case, he said they are more likely to be victims of circumstance based on their living situations.

“A lot of the gang activity that I’ve noticed in this area has been from when the kids were younger and gravitated up until they were in their early 20s,” he said. “This comes with a lot of violence and trying to make a name for themselves on the streets.”

Desmond said he always makes sure he has sufficient evidence to convict, and not just indict.

“I want to prove unreasonable doubt, make sure it’s sufficient and credible evidence,” he said. “The trouble that a lot of people have with it is that some people have a hard time distinguishing the crime from the person.”

Klumpp said most drug court programs in Ohio have a public defendant working on the team to direct eligible cases right into the drug court. Mahoning County’s drug court does not, which makes getting the right drug offenders into the program that much harder.

“It’s still a voluntary program but that certainly gives a lot of people coming their way,” she said. “We have private attorneys who sometimes think it’s too hard for them and don’t even offer it to people, whereas other counties have the public defendants to help them.”

The drug court was able to get a prosecutor to work closely with the team to start identifying individuals who seem appropriate for the program.

“The court does look at everything surrounding a case,” Desmond said. “Their reasons for what they did, their previous criminal record, their future and if they will be a productive member of society or not and the chances of them committing future crimes or not.”

On the road to recovery

Raub is now 10 months clean and well on her way to completing the program in the next six to eight months. She’s completed phase one and two, and now onto the final phase of the program.

One area in her life that she has been working hard on is building and maintaining new friendships and relationships that do not center around drug use. Raub said she is fearful of the judgment she may get from her co-workers and friends after sharing her story on drug use.

“I’m so torn with wanting to scream it from the rooftop that this works and there is such a better life out there if you do it,” she said. “At the same time, that’s not always perceived well. I’m not ashamed of it, but I don’t want to have people treat me differently over it. I have a small group of friends [in the program], but that’s been on my list to expand my friendships.”

Raub said going through her drug recovery this time around was completely different from the first time she got help seven years ago because the first time, she just took away the drugs, but did not change her behaviors or outlook on living a new lifestyle..

“It was always about me, and I didn’t fix any of those problems,” she said. “I’ve never paid [all] of my own bills, and those seem so minimal to the average person, but I never thought I would be here.”

Trauma-informed care — a treatment that focuses on addressing mental health effects of trauma and providing a person with the tools they need for recovery, according to the St. Joseph Institute for Addiction — is the main approach the drug court’s treatment facility takes to provide substance use treatment and counseling to drug offenders, Briceland said.

Drug offenders in the drug court program usually go through intensive treatment for one to two years before graduating from the drug court program completely drug free. They go through three phases while in the program as the first phase is the “most intensive,” Briceland said.

“You come in and we are getting you treatment and everything you need right off the bat and giving you as much support as we can to get them into a more stable place,” she said. “During phase one they come to court every week for status hearings and work with me weekly.”

Treatment is based on a client’s individual need with several treatment programs offered such as a 30 to 60-day residential program, intensive outpatient treatment three times a week, relapse prevention or one-on-one and group counseling, Briceland said.

Raub has been through the 30-day residential program, intensive outpatient and relapse prevention in the past year, she said. She is also on medically assisted treatment and has been taking methadone for nine years to treat her drug addiction.

“That [prescription] saved my life and nothing else was working back then,” she said. “I’m closer to graduating than not, probably like four or five months. I feel I’m not ready for it and I’m afraid of those [future] consequences and accountability being lifted. I feel safe and comfy right now,” she said.

As people in drug court move through different treatment stages, the more solidified their recovery program becomes where they are focused on long-term recovery, Briceland said.

The second phase focuses more on a client’s everyday needs like getting them a driver’s license, social security card and employment to become a more productive member in society, she said. Briceland said clients should be well on their way to recovery and living a sober life by phase three.

“It’s pretty much checking in with them because they have the tools they need, meeting and coming to court every three weeks,” she said. “Getting away from having the court constantly breathing down their necks and having to build that confidence that they can do that by themselves.”

Rood is currently going through intensive outpatient treatment, sober living, trauma therapy, counseling and attends drug court every three weeks for relapse prevention, she said.

Clients who do not follow through with treatments and programming can receive court-ordered sanctions that will set them back even further from graduating the program, Briceland said.

She said one of the biggest keys to completing the program successfully is being held accountable for following through all three phases without receiving sanctions for not going to treatments, missing court meetings or going back to using drugs.

“After so many sanctions or [the client] openly expressed that they don’t have a desire to engage in the program, that’s when we would start to determine if the person is appropriate for the court,” Briceland said.

Rood said she was almost a year sober when she received her first sanction at the end of 2021. She went to jail for two weeks because she wasn’t attending meetings and not living 100% drug free.

“I [also] moved without permission from my parole officer,” she said. “They sat me down in jail for two weeks, but since then I haven’t had any sanctions.”

Most clients struggle with separation from their children or families and not having legal visitation rights because of their substance use disorder.

“As they get their lives together, they want everything to be fixed right away and want to see their kids, so it’s hard for them to accept that it takes more time,” Briceland said.

There are a lot of social factors that go along with substance use.

“We see people who come from families who engage in substance use which started their own journey or younger people being influenced by friends, even people further in their lives and are in an abusive relationship and turned to substances or their partner is using,” Briceland said.

Before graduation, clients must have at least a year clean, live a life of recovery and hopefully have stable employment and housing, so they are able to continue to live the life they have longed for, Briceland said.

“The drug court gives you that team and knowing you can accomplish it, but you must believe in yourself,” she said.

Durkin said initially if someone did not complete the program, they would likely go to prison and would be considered felons. Over time, the program has placed individuals on some level of supervision, community control or probation, instead of prison.

“Even if they don’t successfully complete the program, they will do community control because prison doesn’t work for these individuals,” he said.

Durkin said even if individuals don’t successfully complete the program, the tools and resources that clients get help them discover recovery and turn their life around later on in life.

“The statistics with the people who graduate to those who don’t aren’t necessarily accurate because you never know at some point in time with the tools we’ve given them will help them succeed,” he said.

Judge Baldwin said Mahoning County and the city of Youngstown are rich in treatment programs and resources to help clients stay on the right path and live a life of sobriety.

“We always want them to have a treatment and relapse prevention plan before they graduate,” she said. “We encourage prosocial activities, whether it’s joining a gym, finding a hobby or going back to school.”

One former graduate of the drug court program found herself right back in court when she relapsed on her drug addiction, Klump said. Being able to plant a seed in drug offenders’ minds of what they are able to achieve the second or third time around in the program is the key to long term success.

“I felt at the time we were letting her go too early, and she was back into drugs because of a traumatic situation,” she said. “We saw her booking photo and we knew we needed to get her back. She’s doing wonderfully now and knows the last time what she didn’t do.”

Klumpp said drug offenders in the program are people who have made poor choices and are given an avenue to make better choices for a life filled with prosperity and happiness.

“They can go to other rehab [centers], but they’re not going to be held accountable because they can leave whenever they want and they can’t with us because if they leave, they will have a [legal] consequence with us,” she said.

After Rood graduates the program, she said she plans on becoming a cosmetologist and wants to work for a treatment center to help young adults find a life of recovery like herself.

“I suggest this to everyone that’s going through something,” she said. “This is so much better than going to prison because you can take care of yourself instead of sitting [in prison].”