BIOGRAPHY

As one of Indiana’s

best-known authors, Gene Stratton-Porter left an indelible

mark on the state's history. Her writing started out as a

way to make a little extra money, but it eventually made her

a world famous author and naturalist. Most people know of

Stratton-Porter from her two most famous novels, Freckles

and A Girl of the Limberlost. However, many people

are unaware that she wrote many of her novels to support her

non-fiction writing.

|

Mark Stratton

|

Geneva Grace, later known as Gene, came as a

surprise to her parents, Mark and Mary Stratton. On August

17, 1863, in the small town of Lagro, located in Wabash

County, the couple gave birth to the youngest of their

twelve children. Mary was not well in the years following

Gene’s birth and with a family the size of the Strattons',

there was little time to watch over the youngest. She learned

to play by herself in the outdoors and this solitude became

the foundation for her love of nature.

|

| Mary Stratton

|

However, her happy times on the farm ended with

a series of tragedies that began when she was eight years

old. Her favorite brother, Laddie, drowned on July 6, 1872.

Her brother’s death left a hole in Gene’s heart

and a huge problem for her father. Laddie had been the only

member of the family interested in continuing with farming.

Mark Stratton was sixty years old at the time of his son’s

death and was getting too old to farm. On top of it all, Mary

was still very ill.

|

Gene Age

10 |

In 1875, the family moved from the dearly loved

farm to Largo to stay with one of their daughters. Four months

later, Mary died. After her death, the Stratton family moved

often, living at the homes of Gene's siblings. When Gene was

twenty, she met her future husband.

Charles Porter was a successful druggist and

self-made businessman in Geneva,

Indiana. He first saw Gene when they both attended a Chautauqua

at Island Park Assembly, which was a religious revival, located

on Sylvan Lake. They took up a writing correspondence and

Charles soon asked her to marry him. On April 21, 1886, Geneva

Grace Stratton married Charles Porter and the couple moved

to Decatur, Indiana.

Gene was very unhappy in her first home. Her

husband was constantly traveling between his two stores in

Geneva and Ft. Wayne,

leaving her alone with nothing to do in their small town.

Thankfully, her loneliness did not last long; their first

and only child, Jeannette Stratton-Porter, was born on August

27, 1887. Although Stratton-Porter was no longer lonely, she

found the confined conditions of her home now unbearable with

the new baby.

|

Limberlost

Cabin.

Copyright, Indiana State Museum Shop. |

Soon after the birth of Jeannette, the Stratton-Porter

family moved to Geneva to be closer to one of Charles’s

drug stores. Geneva was an ideal town for Stratton-Porter

because it was near something she was familiar with-- the

Wabash River and her old farmstead. In 1888, Charles Porter

bought his wife a small cottage in the town near his drug

store. The home proved to be too crowded for the family and

they began to build Limberlost Cabin in 1894. In 1895, the

very fine home, costing an astronomical amount, became the

envy of the town.

Gene flourished in Geneva but also became very

frustrated with the naturalists of her time. There were very

few books written about nature and no books available could

answer her questions. In order to find the answers she sought,

Gene Stratton-Porter began to study the birdlife of the upper

Wabash and record her observations. By conducting these studies,

she was able to answer questions about bird physiology and

habits.

Gene’s next problem involved photography.

The only photographs ever taken of birds or animals portrayed

subjects that were dead and stuffed. Gene wanted realistic

photos and sought these pictures in the Limberlost

Swamp. She would photograph and study the wildlife in

the Limberlost for years, recording her findings and turning

those observations into both fiction and non-fiction books.

The Limberlost became a favorite place for Gene and she despaired

when the beautiful trees and natural habitats were cleared

for farmland. Oil drilling also destroyed the land, and she

opposed this practice as well, in spite of the fact that her

husband owned many oil rigs.

When Gene started putting

her observations into books, she found out there were few

publishers that would accept her naturalist writings. To make

her nature books possible, an agreement was made between Stratton-Porter

and her different publishers, such as Bobbs-Merrill, Doubleday,

and Page and Company. Her publishers had serious doubts that

her naturalist books would sell as well as her fiction, so

she agreed to write novels to compensate for the money she

lost on her non-fiction works. Although these non-fiction

works never sold as well as her novels, they were very popular

among some readers.

For example, Moths of the Limberlost

is a natural history study that describes in detail the work

Stratton-Porter accomplished with the moths around her home.

The work was written when readers demanded more information

on the moths found in her novel, A Girl of the Limberlost.

Similarly, What I Have Done With Birds started out

as a study published in a few articles of Ladies Home

Journal, but due to public demand for more information,

Stratton-Porter happily wrote the work to tell all she knew.

|

Wildflower

Woods. Copyright, Indiana State Museum. |

With each work she published, Stratton-Porter’s

fame grew. The public wanted to know more about this strange

woman who ignored social protocol for proper ladies and instead

trodded through dangerous swamps to find more information

on all types of wildlife. Stratton-Porter fans were flocking

to Geneva to visit the famous author. Although their intentions

were well-meant, they soon began to crowd the very private

Stratton-Porter. To escape the attention of her fans, she

left Geneva in 1912 for Sylvan Lake in Rome City. Here, she

bought a small cottage for a short time before searching for

land to build a new house. In October, she found the land

she wanted and began construction on Wildflower Woods. “Out

of more than fourteen thousand trees, vines, shrubs, and wildflowers

that she found or bought and planted, 90 percent were set

by her own fingers” (Long 196). Many of the plants found

at Wildflower Woods were endangered. However, because of the

habitat created by Stratton-Porter, these plants are now flourishing.

Stratton-Porter remained at Wildflower Woods,

planting and creating havens for her bird friends until 1918,

when she could take the destruction of the land around her

no longer. She moved to the beautiful landscape of southern

California and remained there, writing several more books,

producing quite a few movies, and even starting to publish

some of her poetry. However, her poetry does not focus on

Indiana's environment. Stratton-Porter lived in California

until her death at the age of sixty, on December 6, 1924,

when she suffered fatal injuries from an automobile accident.

FICTION

Gene Stratton-Porter is best known for her novels

Freckles (1904) and A Girl of the Limberlost

(1909), which put Geneva,

Indiana, and the Limberlost

Swamp on the map. Of all her books, these two have most

successfully brought attention to Indiana's environmental

concerns. Readers who are completely in tune with nature and

who find fulfillment through its healing qualities are easily

absorbed into the characters of her novels.

The Song of the

Cardinal (read

full text), published in 1903, was Gene Stratton-Porter’s

first novel. It tells the story of a male cardinal living

his life on the land of a farmer who has promised sanctuary

for all birds residing there. Porter was inspired to write

the book when she found a dead cardinal, the victim of thoughtless

sport. She was so irate that she wrote this book in response.

The book centers around a cardinal who is separated

from his family and must live on his own. He flies until he

finds an orchard to live in, and there he meets Abram, who

talks to him, offering advice and protection.

Abram, the farmer, was clearly based on Stratton-Porter's

father, who in her childhood promised her all the birds on

his land as a gift. They would be protected from hunters as

long as he owned the land.

Abram regards the cardinal as an equal, and this

concept of equality is explored as the book progresses. Through

the song of the cardinal, Abram and Maria, his wife, gain

a stronger appreciation of nature.

[Abram’s] heart was big with happiness.

It was the golden springtime of his later life. The sky

never had seemed so blue, or the earth so beautiful. The

Cardinal had opened the fountains of his soul....

(103) (extended

quote)

Another manifestation of this appreciation is

apparent when at one point in the novel, a young man is caught

hunting on the land, and Abram explains to him why he should

not kill for sport. The boy is so sorry for his actions that

he confesses his wrongdoing, drops his gun, and runs off of

the property.

Stratton-Porter's next

novel, Freckles

(read full text), was published

in 1904. It is the story of a young orphan, nicknamed Freckles,

who has only one hand. Because he is different, Freckles has

faced harsh treatment throughout his life, but he eventually

obtains a job working for McLean, the manager of a big lumber

company. Freckles must live in the Limberlost

and protect it for the next year. Although he is alone, the

experience of living in the swamp proves to be beneficial.

When the first breath of spring touched

the Limberlost... and the pulse of the newly resurrected

season beat strong in the heart of nature, something new

stirred in the breast of the boy.

Nature always levies her tribute. Now

she laid a powerful hand on the soul of Freckles, to which

the boy’s whole being responded, though he had not

the least idea what was troubling him.... Clean, hot, and

steady the blood pulsed in his veins. He was always hungry,

and his hardest day’s work tired him not at all....

He had taken on flesh and colour, and developed a greater

strength and endurance than any one could ever have guessed.

(40-1)

(extended quote)

Being in nature strengthens Freckles,

both mentally and physically. He is bribed to let McLean's

ex-workers cut down a few trees, but he refuses the money

instead of betraying his duties.

Freckles meets and falls in love with Swamp

Angel, a frail but beautiful young woman who lives in the

Limberlost with the Bird Woman. This was a real-life nickname

for Gene Stratton-Porter, and like the author, the Bird Woman

photographs birds and collects insects.

“[The Bird Woman is] dead down on

anybody that shoots a bird or tears up a nest. Why, she’s

half killing herself in all kinds of places and whether

to teach people to love and protect the birds. She’s

that plum careful of them that Jim’s wife says she

has Jim a standin’ like a big fool holding an ombrelly

over them when they are young and tender until she gets

a focus, what ever that is. Jim says there ain’t a

bird on his place that don’t actually seem to like

to have her around after she has wheedled them a few days,

and the pictures she gets nobody would ever believe that

didn’t stand by and see them taken.” (114)

Freckles helps the women with their nature studies

and provides them protection. Like Stratton-Porter herself,

the Swamp Angel condemns the destruction

of the forests, as in this passage:

“Oh, what a shame!” cried

the Angel. “They’ll clear out roads, cut down

the beautiful trees, and tear up everything. They’ll

drive away the birds and spoil the cathedral. When they

have done their worst, then all these mills about here will

follow in and take out the cheap timber. Then the land-owners

will dig a few ditches, build some fires, and in two summers

more the Limberlost will be in corn and potatoes.”

(182-3)

At the Foot of

the Rainbow,

(read full text) published in 1907,

is the story of two life-long friends, Jimmy Malone and Dannie

Micnoun. They live near Rainbow Bottom along the Wabash River,

where they hunt, fish, and tend their farms.

The two characters have many differences; Jimmy

often misunderstands his surroundings, but Dannie is in touch

with the Earth. By emphasizing their dissimilar approaches

to nature, Stratton-Porter shows readers the value of appreciating

the environment. Here Dannie expresses his wonder at the splendor

of Rainbow Bottom:

“I dinna think there is ony place

in all the world so guid as the place ye own,” Dannie

said earnestly.... “I dinna give twa hoops fra the

palaces men rig up, or the thing they call ‘landscape

gardening.’ When did men ever compete with the work

of God...? The thing God does is guid enough for me.”

(103-5) (extended

quote)

Jimmy is interested in material things, but Dannie

finds the forest

and all of nature fascinating and full of life. He prefers

natural beauty over artificial “landscape gardening,”

and he compares Rainbow Bottom to an endless pot of gold,

a marvelous wealth of infinite beauty.

Stratton-Porter's most famous

novel, A Girl of the Limberlost (read

full text), was published in 1909. It is the story

of Elnora Comstock, a girl who lives in the Limberlost with

her widowed mother. (read

quote)

Elnora convinces her mother to let her go to

school, but when she arrives, she is embarrassed by her inferior

clothes and lack of textbooks. Mrs. Comstock refuses to buy

Elnora's books, so she sets out to earn the money herself.

Elnora responds to a sign in a bank window offering

cash for caterpillars, cocoons, chrysalides, pupae cases,

butterflies, moths, and Indian relics of all kinds. Having

explored the Limberlost

and amassed an extensive collection of insects and other specimens,

Elnora finds the Bird Woman, who had posted the sign, and

soon has the money she needs for school. (read

quote) However, that money runs out over the next

few years, so Elnora must once again begin collecting.

At one point, Mrs. Comstock spots an insect in

the house and kills it before Elnora can stop her. The insect

is a Yellow Emperor, a rare moth which Elnora needs to complete

a set worth 300 dollars. To rectify her mistake, Mrs. Comstock

goes into the Limberlost to search for a Yellow Emperor herself.

As Elnora and her mother find insects together, their relationship

grows stronger.

While searching with her mother one day, Elnora

meets a man in the forest who offers to help her cut a cocoon

from a log.

“It’s going to be a fair job

to cut it out, but when it comes, it is not only beautiful,

but worth a price; it will help you on your way. I think

I’ll put up that rod and hunt moths." (264)

(extended quote)

The man, named Philip

Ammon, has been instructed by his doctor to spend time outdoors

to recover from typhoid fever. He decides to help Elnora with

her hunting since he must exercise outside anyway.

Philip and Elnora spend the summer together hunting

moths and other insects. She obtains a job at the school teaching

about the wilderness. Elnora and Philip become good friends

and eventually get married.

The Harvester

(read full text), published in

1911, tells of a man who lives his life in the woods collecting

plants for medicinal use and selling them to chemists. The

Harvester has a dream of a beautiful girl and devotes his

time and effort to finding her. (read

quote) He lives most of his life in the 600 acres

of a forest called Medicine Woods, and collects plants from

surrounding areas to grow on his own property.

Six years he had worked cultivating these beds,

and hunting through the woods on the river banks, government

land, the great Limberlost Swamp, and neglected corners of

the earth for barks and roots. He occasionally made long trips

across the country for rapidly diminishing plants he found

in the woodland of men who did not care to bother with a few

specimens, and many big beds of profitable herbs, extinct

for miles around, now flourished on the banks of Loon Lake,

in the marsh, and through the forest rising above. (26)

The Harvester eventually does find his “Dream

Girl,” whose real name is Ruth Jameson. Ruth is ill

when the Harvester first meets her, and he tries to cure her

from her sickness, teaching her, in the process, about the

forest and its many uses. They marry, but she does not yet

love him. Again, Ruth becomes very ill and nearly dies, and

when none of the doctors can help her, the Harvester treats

her with a concoction of his own. He continues to care for

her, and by healing her body and her soul, he finally wins

her love.

Many aspects of the Harvester’s life in

the woods affect his personality and actions throughout this

book. They are his respect for nature and the way this respect

is tied to his religion. (read

quote)

He respects nature and does not take from it

in excess. “I must have a mighty good reason before

I kill…. I cannot give life; I have no right to take

it away” (173).

As important as nature is to him, there is something

that holds a higher priority: his religion. His is a simple

religion but he is very devoted to it. His respect and wonder

at nature stems from his religion. He expresses it in the

woods

where he works and lives. "My work keeps me in the woods

so much I remain there for my religion also. Whenever I find

these flowers I always pause for a little service of my own..."

(183).(extended

quote)

The Harvester ties together well the ideas of

nature and religion. (read

quote) This was a concept of which Stratton-Porter

was very fond. Through this connection, greater importance

is put on nature, which is what she wants to do in order to

help preserve it. The Harvester conveys this idea to the reader.

In 1913, Stratton-Porter

published Laddie: A True Blue Story

(read full text), which is strongly

based on her own life. The narrator, Little Sister, is a girl

who lives on a farm with her older siblings. (read

quote) The oldest of these siblings, Laddie, is

a strong influence on her life.

Little Sister's is interested in nature and that

interest can be clearly traced to her father:

Every few days I followed the lane as far

back as the Big Gate. This stood where four fields cornered,

and opened into the road leading to the woods.

Beyond it, I had walked on Sunday afternoons with father

while he taught me all the flowers, vines, and bushes he

knew, only he didn't know some of the prettiest ones….(8)

(extended

quote)

As Little Sister grows, she realizes

the value of experience in learning about nature. Although

schooling and books teach her the names of plants and animals,

it is only by being outside and observing her environment

that she truly learns about nature. (read

quote)

Like Stratton-Porter, Little Sister was not meant

for a life indoors. Her joy in life is being with nature,

not living and working in confined rooms. (read

quote) This novel is a good one to read

to understand Stratton-Porter’s childhood and how it

later affected her life and work. It is as important as a

biography, because it is written by Stratton-Porter about

herself.

Stratton-Porter's novels have touched the lives

of countless Hoosiers, as well as many others. Her fictional

works reveal an environment where many of her characters have

grown and been healed by nature. Unfortunately much of that

environment no longer exists today.

--BJF

NON-FICTION

Gene Stratton-Porter may be best known for her

novels, but her true love was writing about natural history.

Most of her novels were only written to fund her nature writing.“[I]t

was her clear objective to promote the preservation

of the physical landscape that inspired…her” (Vanausdall

103). She could often be found in the swamp,

photographing, studying, and writing about the animals around

her. The biographer Frederic Cooper commented:

Gene Stratton-Porter lives in a swamp, arrays herself in

man’s clothes, and sallies forth in all weathers to

study the secrets of nature. I believe she knows every bug,

bird, and beast in the woods…She

is primarily a naturalist, one of the foremost in America

and has published a number of books on flora and fauna…

These books—which are closest to her heart—have

only a moderate sale. (670)

Several of her natural history books contain

her photography of living specimens she found in the Limberlost

swamp. Birds and moths were her favorite subjects to write

about and photograph, but her interest reached beyond these

creatures. She became an expert on Indiana’s natural

world, particularly her beloved Limberlost. In Gene Stratton-Porter:

A Lovely Light, she is quoted:

I was born in this state, have always lived

here and hope to die here. It is my belief that to do strong

work any writer must stick to the things he truly knows,

the simple, common things of life as he has lived them.

So I stick to Indiana (82).

Her first natural history

work was What I Have Done with Birds: Character

Studies of Native American Birds. This book

was published in 1907, and a revised edition was published

in 1917 as Friends in Feathers. The book is an account

of many species of birds that Stratton-Porter studied over

the course of five years, including photographs that she took.

In each chapter, she discusses a different species of bird

and her experiences in the field with that species. She describes

in intimate detail her encounters with birds in the Limberlost

and how she photographed them in their natural habitat. Her

strong feelings against harming an animal or its surroundings

for the sake of nature study or photography are evident.

The greatest brutality ever practiced on brooding

birds consists in cutting down, tearing out and placing

nests of helpless young for one’s own convenience.

Any such picture has no earthly value, as it does not reproduce

a bird’s location or characteristics. (13)

Birds of the

Bible was published in 1909. In this work Stratton-Porter

meticulously discusses psalms and passages in the Bible that

mention birds. She writes that birds are often a religious

symbol because “[f]eathered creatures have a beauty

of form and motion…[therefore] we love the birds, and

whoever writes of them with a touch of the divine tenderness

of poesy makes instant appeal to our hearts.” (115)

Only a year later, Music

of the Wild, with reproduction of the performers, their instruments

and festival halls, was published. This book

contains over one hundred of Stratton-Porter’s photographs

and is spilt into three sections: The Chorus of the Forest,

Songs of the Fields, and Music of the Marsh. Here she refers

to the natural song of the Limberlost:

“[N]one…can sing sweeter songs or have more interest

to the inch than the Limberlost” (289). She challenges

her reader to listen to nature’s music and learn to

hear each player and enjoy every note.

Always there is the call of the music; the

best in the wide world, the spontaneous, day long, night

long song of freedom and content. From a million gauze-winged

magicians, from the entire aquatic orchestra singing to

the accompaniment of the pattering rain, from the killdeer’s

call trailing across the silver night, from the coot waking

the red morning, from the chattering blackbird of golden

noon, from the somber-robed performers of the gray evening,--comes

the great call that above all lures men to return again,

and yet again, to revel in it; comes the sweet note from

the voice of the wild…. (426-7)

In

1912, one of Stratton-Porter’s better-known natural

history books was published. Moths of the Limberlost

(read

full text) is a detailed natural history

of her experiences and study of moths. The original edition

of this book included many of Stratton-Porter’s photographs

of moths in various stages of life. She describes in the book

how the study of moths became one of her passions:

Primarily, I went to the swamp

to study and reproduce the birds. I never thought they could

have a rival in my heart. But these fragile night wanderers,

these moonflowers of June's darkness, literally "thrust

themselves upon me." When my cameras were placed before

the home of a pair of birds…and clinging to them found

a creature, often having the bird's sweep of wing…the

feathered folk found a competitor that often outdistanced

them in my affections, for I am captivated easily by colour,

and beauty of form. (127)

Moths of the Limberlost

has detailed descriptions of Stratton-Porter’s work

in raising, studying and photographing moths. This book is

a detailed natural history of the moths found in the Limberlost

area. In this work, Stratton-Porter’s fascination with

these insects is obvious. “If only one person enjoys

this book one-tenth as much as I have loved the work of making

it, then I am fully repaid”(386). She encourages her

readers to help the moths and welcome them into their yard.

I think people need not fear planting trees

on their premises that will be favourites with caterpillars…[I]

never have been able to see the results by a single defoliated

branch…If you care for moths you need not fear to

encourage them; the birds will keep them within proper limits.

(49)

Homing with

the Birds, published in 1919, begins with stories

about her childhood on her parents’ Hopewell Farm in

Wabash County, Indiana.

She describes her first experiences with birds and how she

earned the title “little bird woman” early in

her life. Later

she talks about an important experience where her father gave

her a life-changing gift.

…[H]e told me that he had something

for me even finer and more precious than anything man had

made or could ever make…he then preceded formally

to present me with the personal and indisputable ownership

of each bird of every description that made its home on

his land. (21)

She also discusses many unusual things she had

seen and photographed, as well as her interpretations of bird

songs, languages and general natural history including instinct,

courtship and nest-building. This book was written after she

moved to her Limberlost Cabin North in Rome City, Indiana.

Her move was a result of the disgust she felt as she watched

the destruction

of the Limberlost.

Through the work of farmers and lumbermen,

my immediate territory had been cleared, drained, and put

under cultivation, until the birds had flown, the flowers

and moths were exterminated, there was not an interesting

landscape to reproduce. (66)

She goes on to explain

that even in Rome City there were people who lacked concern

for the environment:

If these men do not take active conservation

measures soon, I shall be forced to enter politics to plead

for the conservation of the forests,

wildflowers, the birds, and over and above everything else,

the precious water on which our comfort, fertility, and

life itself depend. (123)

Later in the book, she makes a plea

for consciousness to the environmental issues connected to

birds, such as eliminating exotic species and preserving endangered

species. “I hope I have gone into

sufficient detail to prove to anyone reading this book the

sum of our indebtedness to the birds. The question now becomes:

how can we pay our obligation?” (365). Stratton-Porter

closes with a final entreaty,

“In the writing of this book I have done my best. Now

is the time for concerted action on the part of everyone who

reads it” (376).

Wings

was published in 1923. It was similar to the books she had

published earlier about the natural history of birds and her

experiences with them.

In 1925, after Stratton-Porter’s

death, Tales You Won’t Believe

was published, which was a collection of stories from her

life in the field. She wrote this book almost entirely about

her experiences at Limberlost Cabin North in Rome City, Indiana.

She discusses her love for the land around her and its rich

habitats and variety of wildlife. She writes of a beautiful

wood duck that she comes upon while studying at Sylvan Lake.

Sadly, the duck is shot later that same day.

The fact that June was the time for nesting;

that they had broken the laws of man when they killed the

mate of a brooding bird; they had broken the laws of God

when they took the life of intense interest and exquisite

beauty…because in all the work I have done in the

woods and around the water, that is the only wood duck I

have ever seen, and I am perfectly confident that none of

us will ever see another. (153-4)

She also tells the story of the last passenger

pigeon, an extinct species. In this story she also complains

about the clearing of the land:

[M]an started to clear a piece of land he

chopped down every tree on it, cut the trunks into sections,

rolled them into a log heap, and burned them to get them

out of his way…Now where was there even one man who

had the vision to see that the forests

would eventually come to an end…? (212)

She points out that this habitat destruction

would have devastating results including climate change, “They

had forgotten that draining the water from all these acres

of swamp

land would dry and heat the air…and they had not figured

out for themselves how much rainfall they would take from

their crops” (173). She continues: “[A]s the forests

fell, the creeks and springs dried up…the work of changing

the climatic conditions of a world was underway…the

fur-bearing animals and all kinds of game birds were being

driven farther and farther…” (213). She also discusses

the environmental issues associated with agriculture:

“I must gather all the beautiful things I could that

lay in the way of clearing and draining on the individual

land of each farmer who wanted to increase his tillable area”

(172).

Her last natural history book,

Let Us Highly Resolve, was published

in 1927. It is a collection of environmental essays, the most

stirring of which is entitled “Shall We Save Our Natural

Beauty?” She explains the changes that Indiana’s

environment has experienced:

I was accustomed to Indians at the door, to

wild turkeys, wildcats, and bear and deer in the woods…We

used to see pigeons come in such numbers that they broke

down branches…There was an abundance of game of every

kind…The resources of the country were so vast that

it never occurred to any one to select the most valuable…and

store them for the use of future generations. (181)

Stratton-Porter goes on

to examine the negative effects of clearing and exploiting

the land, pleading for nationwide conservation efforts:

The deer and fur-bearing animals are practically

gone from the country I knew…The birds have been depleted

in numbers until it is quite impossible to raise fruit of

any kind without a continuous fight against slugs and aphis…With

the cutting of timber has come a change in climate; weeks

of drought in the summer…and winters so stringently

cold that the fruit trees are killed outright. The even

temperature and the rains every three or four days which

we knew in childhood are things of the past…it has

become necessary for the sons of the men who wasted the

woods

and the waters to put in overhead sprinkling systems…

windmills and irrigation are becoming common…as a

nation, [we] have already, in the most wanton and reckless

waste the world has ever known, changed our climatic conditions

and wasted a good part of our splendid heritage. The question

now facing us is whether we shall do all that lies in our

power to save comfortable living conditions for ourselves

and the spots of natural beauty that remain for our children…If

this is to be done, a nation-wide movement must be begun

immediately...there may not be coal and iron, at the rate

we are using it, to supply future generations…Certainly

to plant trees and preserve trees, to preserve water, and

to do all in our power to save every natural resource, both

from the standpoint of utility and beauty, is a work that

every man and woman should give immediate and earnest attention”

(194).

From Stratton-Porter's natural

history works, readers can gain a sense of the history of

environmentalism in Indiana. The influence of her works was

not contained by Indiana's borders. Her passion for the environment

and her meticulous methods for studying it have inspired people

around the world.

--KMS

MAGAZINE ARTICLES

Gene Stratton-Porter was monumental in bringing

the nature of Indiana into the homes of families around the

United States. Her writings about a small town swamp

and the environment outside her window brought new perspectives

on nature to many Americans.

Stratton-Porter was unsatisfied with the money

her husband allotted her, so she began writing her magazine

articles to earn extra money. However, the public soon took

to her writing, and Stratton-Porter found herself responding

to the mail of eager fans by undertaking new studies and writing

articles.

One of her very first articles,

Why the Biggest One Got Away, published

in Recreation Magazine, focused on the Wabash

River and the fishing she and her family did in that area.

She loved nature and tried to express in her writings the

serenity she gained from spending time outdoors. Her love

for birds also played heavily in many of her articles.

A

few examples of Stratton-Porter's bird studies may be found

throughout the Outing Magazine publications, most

taking place in the Limberlost

Swamp or surrounding areas. Published in the July 1901

issue, “Bird Architecture ” describes

her study of the various birds found throughout the Limberlost

Swamp. In the November 1901 copy, “Photographing

the Belted Kingfisher,” Stratton-Porter

depicts the habits and characteristics of the Belted Kingfisher.

|

Black Vulture.

Photo by Gene Stratton-Porter |

One of her more exciting

studies involves the article, “A Study of the

Black Vulture,” published

in December 1901. A rare find in the 1900s, a vulture nest

was nearly impossible to spot and little was known about the

bird. Stratton-Porter visited the spot of the nest for weeks,

braving the terrible swamp

with its bugs and poisonous snakes to present a new perspective

on the often ill-regarded bird.

Stratton-Porter

describes her observations of animals' senses in the June

1902 issue of “Sight and Scent in Birds and

Animals” and creates a symphony of sounds with

her September 1902 article, “The Music of the

Marsh.”

With these articles Stratton-Porter

hoped to show people the often-overlooked beauty and complexity

of wildlife. She felt that the people of her time were too

concerned with propriety and social affairs, and she wanted

them instead to appreciate the natural world. She stressed

the importance of taking the time to observe nature to all

her readers, whether they lived in the city or the countryside.

Such opinions are found in the article, "Under

My Fig Tree," published

in The American Annual of Photography and Photographic

Times Almanac for 1903. For example:

There come at home days when I do not know

of a single location anywhere to tempt me abroad, and I

say to myself, “To-day, about my veranda and orchard

I will loaf and invite my soul.” It is of these days,

under my own vine and fig tree, when most interesting subjects

come and sit down in front of me, and as it were, compel

my camera from its case and my lens to action, that I wish

to write. (26)

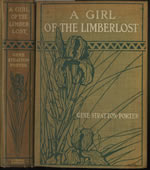

|

A Girl of

the Limberlost. Published by Doubleday Page and Company,

1909. |

In the February 1910 issue

of World’s Work Magazine, Stratton-Porter wrote

the article “Why I Wrote A Girl of the Limberlost.”

Letters poured in after the publication of this novel and

the public asked for more. Stratton-Porter wrote this article

in response. In this article, she again notes her desire to

bring the tranquility of nature and the forest

to the public:

So I wrote “A Girl of the Limberlost,”

to carry to workers inside city walls, to hospital cots,

to those behind prison bars, and to scholars in their libraries,

my story of earth and sky… I put in all the insects,

flowers, vines and trees, birds, and animals that I know….

(12546)

Stratton-Porter continued to write about Indiana’s

environment in popular magazines like Outing, Ladies Home

Journal, Good Housekeeping, and McCall’s

as well as many others, and showed people a new world waiting

in the swamps and forests.

Although Stratton-Porter

was sometimes criticized for being too sugary, this did not

stop readers from devouring her work. In 1921, she signed

a contract with McCall’s Magazine to write

a monthly article called the Gene Stratton-Porter Page.

As her audience was composed of mainly women, the articles

gave advice on housekeeping as well as addressing nature topics.

This column appeared in each issue of McCall’s from

1922-1927. Even after her death in 1924, the fans longed to

read all she had to say, and the remainder of her articles

were published posthumously. In December 1927, her final article,

"The Healing Influence of Gardens,"

was published in McCall's. In this article, her daughter addressed

the readers, making this statement about Stratton-Porter’s

feelings toward the fans:

|

Jeannette Stratton-Porter,

1907.

|

I do not know which was dearer to my mother’s

heart – Nature, with all the wealth of color and beauty

that word implies – or you, women of America, two

million strong, to whom she spoke each month through this

page. That she loved you both I am certain. Her love for

Nature – for flowers, for fields, for streams, for

mountains, spoke through every word of her works. Her love

for you shone through her life and illuminated each tiny,

inconsequential daily task. You were always in her thoughts,

you women of McCall’s street; your problems

were her problems, your hopes her hopes and your triumphs

she made her own. My mother is gone, but her love and her

spirit, I am proudly confident, remain and will be forever

with you. (120)

Stratton-Porter wrote her articles to give people

a glimpse of the world outdoors. Their response to her editorials

was one factor in her decision to expand many of her articles

into books. For example, Freckles, Laddie, Moths of the

Limberlost, What I Have Done With Birds, and The

Song of the Cardinal all started out as articles. Stratton-Porter’s

readers loved her writings so much, that they demanded her

articles be published even after her death. Stratton-Porter

contributed to the environment and literature by creating

novels that educated as well as entertained their readers.

--DSS

Sources:

Cooper, Frederic Taber. "The

Popularity of Gene Stratton-Porter." The Bookman

9 (1915): 670-71.

Gene Stratton-Porter: A Voice

of the Limberlost. Producers Nancy Carlson and Ann Eldridge.

Perf. Annette O’Toole. Ball State University, 1996.

King, Rollin. Gene Stratton-Porter:

A Lovely Light. Chicago: Adams Press, 1979.

Long, Judith Reick. Gene Stratton-Porter:

Novelist and Naturalist. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical

Society, 1990.

Richards, Bertrand F. Gene Stratton-Porter.

Boston: Twayne, 1980.

Stratton-Porter, Gene. At the

Foot of the Rainbow. New York: Grosset & Dunlap,

1907.

---. Birds of the Bible.

Cincinnati: Jennings & Graham, 1909.

---. A Girl of the Limberlost.

New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1909.

---. Freckles. New York:

Doubleday Page & Co., 1904.

---. The Harvester. New York:

Doubleday Page & Co., 1911.

---. Homing with the Birds:

The History of a Lifetime of Personal Experience with the

Bird. New York: Doubleday Page & Co.,1919.

---. Laddie: A True Blue Story.

New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1913.

---. Let Us Highly Resolve.

New York: Doubleday Page & Co., 1927.

---. Moths of the Limberlost.

New York: Doubleday Page & Co., 1912.

---. Music of the Wild. Cincinnati:

Jennings & Graham, 1910.

---. The Song of the Cardinal.

New York: Doubleday Page & Co., 1915.

---. Tales You Won't Believe.

New York: Doubleday Page & Co., 1925.

---. What I Have Done with Birds:

Character Studies of Native American Birds. Rev.

ed. as Friends in Feathers. New York: Doubleday Page

& Co., 1917.

---. Wings. New York: Doubleday

Page & Co., 1923.

Vanausdall, Jeanette. Pride and

Protest: The Novel in Indiana. Indianapolis:

Indiana Historical Society, 1999.

(MAGAZINE

BIBLIOGRAHY)

Images:

Long, Judith Reick. Gene

Stratton-Porter: Novelist and Naturalist. Indianapolis:

Indiana Historical Society, 1990. 22, 23, 67, 101, 116, 156.

[Family photos and vulture picture.]

A Girl of the Limberlost.

Rave Reviews: Bestselling Fiction in America Exhibit, U of

Virginia Library. 15 November 2002 <http://www.lib.virginia.edu/speccol/exhibits/

rave_reviews/lg_html/1909-girloflimberlost-cove.html>.

Links:

Indiana

Historical Society: Gene Stratton-Porter

Gene Stratton-Porter

and Her Limberlost Swamp

|