Addict called to start recovery home

November 9, 2016

Drug Court’s success

November 9, 2016Mother, daughter duo fight to help addicted babies

More than two babies are born drug addicted every week at IU Health Ball Memorial Hospital.

“There’s hardly ever a time when we don’t have a baby in withdrawal in our NICU,” said Kelly Leonard, who has been a nurse in the hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit the past 25 years and has been shift coordinator for the past two years.

Kelly said of the 1,400-plus deliveries last year, 15 percent were tested for maternal drug use and 8.5 percent came back positive. The statistic is even more severe nationwide. In 2013, according to the latest available data from the Center for Disease Control, a baby was born addicted to narcotics every 25 minutes in the U.S.

Kelly’s daughter, Kylie, also works in the NICU as a volunteer.

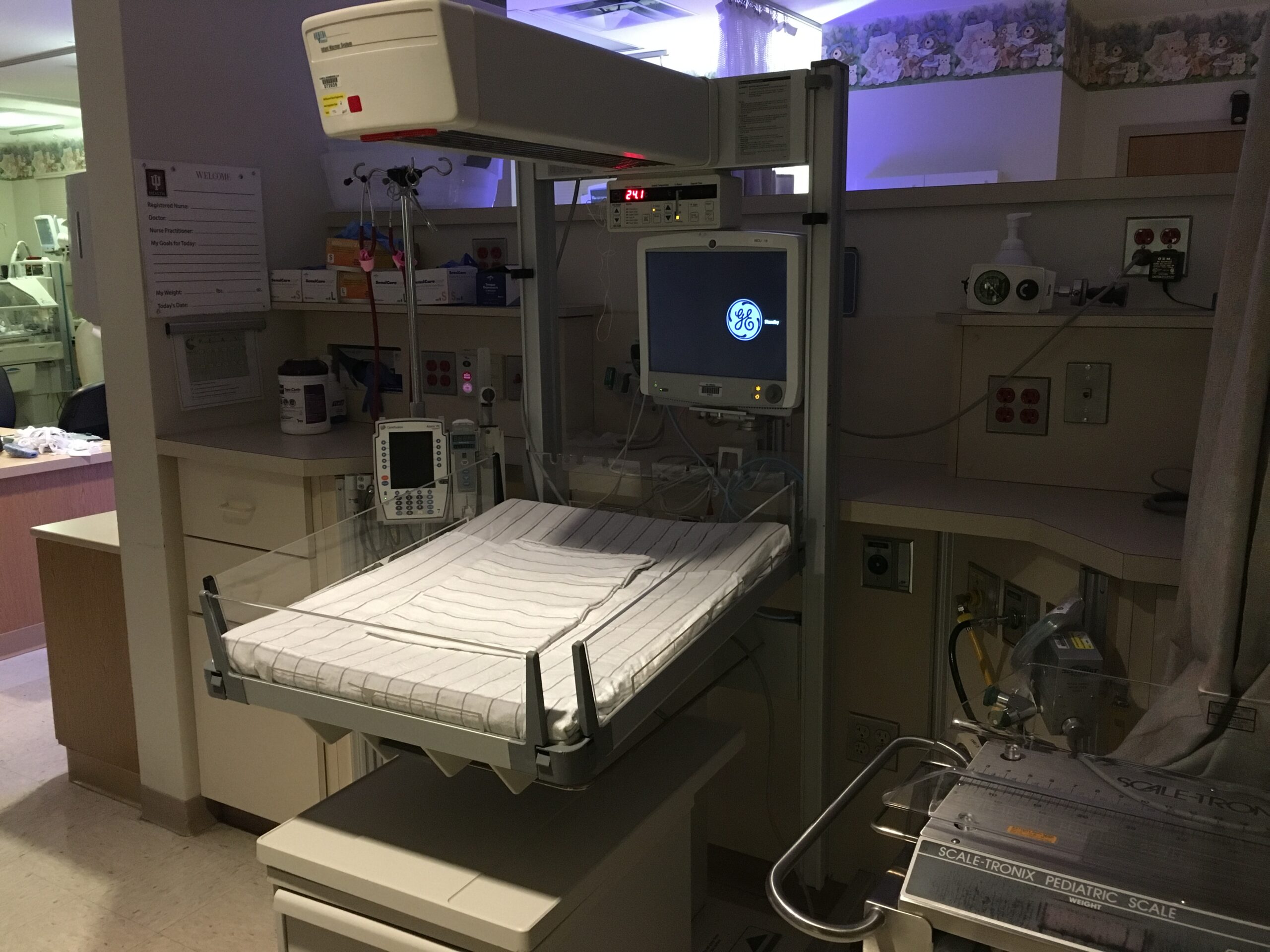

Upon entering the NICU, multiple things barrage the senses: the buttery, warm smell of a newborn, the rhythmic beat of multiple heartbeat monitors and the flutter of nurses tending to tiny babies.

About 20 infants usually occupy the NICU at any one time. The coos of the premature babies are almost soothing and combine to fill the room with a symphony of happiness. But, in the corner of the room, there is a baby with a very different type of cry. It’s a cry that Kelly and Kylie know all too well. It is the distressing scream of an infant in withdrawal.

It’s a baby in pain.

In fact, this phenomenon has become so ubiquitous that it has been given a name, Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, or NAS, and Muncie is no stranger to this national epidemic.

According to the latest available data from the New England Journal of Medicine, admissions of infants suffering from withdrawal into NICUs nationwide have nearly quadrupled from 2004 to 2013.

Kylie Leonard helps administer care to the victims of neonatal abstinence through the Cuddler program, which enlists the support of volunteers to give NAS babies stimulation, and to comfort them when they are in pain or distress. The cuddlers are assigned to babies for their entire shift. They have skin-to-skin contact with the babies, they read to them, sing them lullabies and change their diapers.

The cuddlers do everything they can to make these babies comfortable, especially when babies are suffering from the painful symptoms of withdrawal.

Free spaces on the NICU walls are decorated with signs for each baby. One indicates with sparkles and various shades of pink that a princess is sleeping in her crib. Another dons the goals the nurse made for the day to be accomplished by a tiny baby boy. The NICU at Ball Memorial does everything it can to make certain these babies are cared for and comforted.

“These [NAS] babies are very miserable,” Kylie said. “They’ll have shaking fits. I wouldn’t quite describe them as seizures, but they will shake and they will scream. A scream from them is completely different. You can hear the pain. It’s uncontrollable. Once they get to that state, it’s hard to calm them back down.”

Around 10 years ago, Leonard and her coworkers began to notice an increase in babies addicted to painkillers and other drugs.

“That’s really when we had the birth of [our] Cuddler program,” said Kelly. “People had heard about (the increase in addicted babies) in big cities for a long time, and when we did start seeing it, that’s when we established our Cuddler program.”

Aside from the agonizing screams that come from NAS babies after they’re born, there are other indicators that a mother has been using.

“We wouldn’t even need to know that they were positive for meth, specifically,” said Kelly. “They can’t sit still.” Heroin moms, on the other hand, tend to be sluggish and sleep for extended periods.

The Finnegan scoring system, a narcotics withdrawal scale, is also used. If the baby’s score is too high, he or she will be moved into the NICU for monitoring and treatment. Scoring looks for tremors, muscle tone, convulsions, sweating and the telltale sign, the high-pitched cry.

In 2014, the Indiana General Assembly added legislation that required the State Department of Health to establish a task force to study and work on improving the state’s issue of NAS babies.

The NAS task force created a report that came up with ways to spot NAS babies early, how to test for NAS and other ways to help mothers and their children.

Article continues after video.

Katiena Johnson’s daughter is an addict. Although her drug of choice is heroin, she has also done meth. Here she talks about what it is like loving an addict and the struggles that come along with it. Michael Kuhn reports.

“Withdrawal from drugs can have a life or death impact on that baby,” Kelly said. “Since that time, and noticing all those babies, we’ve started doing more comprehensive testing, and we’ve noticed babies who are addicted.”

Most times, the mother also is aware of the withdrawal and symptoms. They are usually honest with their physicians, even if they haven’t been honest with themselves or their loved ones.

“Oftentimes, they have limited resources and abilities to even come into the NICU, or they have other kids,” Kelly said. “Often times, their other kids have been taken away. There’s a lot of guilt. They’re very ashamed that their baby is in there. Sometimes they have a problem of addiction that they’ve kept from their family.”

Families are, arguably, the most affected when it comes to drug use, and a tiny infant, suffering with shaking fits, might not even get to experience the family they would have had if the mother had not been doing drugs.

For the safety of the baby and the family, the NICU at Ball Memorial has to let authorities know about the mother’s drug use.

“Child Protective Services is always involved,” Kelly said. “Sometimes the babies go home with the parents, sometimes there’s counseling, sometimes moms will go through a treatment program, sometimes the baby goes to a relative until mom can get herself together and sometimes the babies actually go to foster care if there are no relatives that are appropriate.”

Dana Gault, the office director of the Indiana Child Protective Services in Delaware County said there is a specific protocol that they have to follow when they receive a call from the hospital about a baby with NAS.

The CPS member goes to the hospital, meets with the parents, records the mother’s history then checks out the home. Next, is a family meeting to find out whether the mother has the support she needs to take care of the baby.

All of these factors, along with the type of drug being used, go into the final decision of whether or not to remove the baby from the home.

“If it’s meth or heroin, we’ll probably take the baby,” Gault said. “Because meth and heroin comes with the environment of needles and needle sharing … It’s a whole other safety concern.”

Kelly said most NAS babies usually are diagnosed before delivery. Physicians can tell, the nurses can tell and the mothers can tell.

Mothers let their physicians and staffs know they have been addicted to drugs because usually they want what’s best for their baby.

“Some of them, when they reach the point of realizing what’s happened to their baby, they want it so that no one else has to go through that,” Kylie said. “Having to have to see your baby go through withdrawal in the NICU.”

One of the most important things that the mother/daughter duo preaches is that drugs affect everyone. Not just individuals of low income. Not just people with the stereotype of “white trash.” Not just people with unfortunate stories that have become increasingly common in the news.

“Drug use in Delaware County … We actually find we have had withdrawal babies from rich families, from poor families from middle-class families. We have had different racial demographics represented for the most part in our community.”

Kelly and Kylie Leonard say they have been forever changed by their experiences in the NICU. They are dedicated to helping those who cannot help themselves.

“I’m a 22-year-old blonde, white girl who never knew this world existed until I started volunteering a year-and-a-half ago,” Kylie said. “It’s the most painful, emotional experience … you go in there so positively, thinking, ‘I’m going to help these people.’ Then you at some point realize that ‘I can’t help them for the long term, but I can help them during this shift because right now the nurses need me and this baby needs me.’ ”