Conclusion

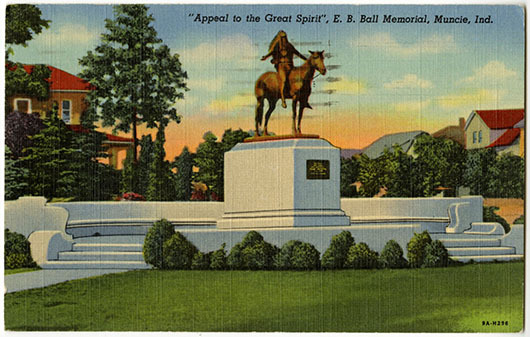

The vibrant colors of this postcard illustration contrast with the empty scene. Nothing is happening in the park around the statue. It is eerily still, perhaps waiting for someone to come along and appreciate the statue of a man who never was. In contrast, a great deal was happening in the lives of this semester's notable women. In 1929 when Bertha Ball commissioned this statue, the forced repatriation of thousands of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans living in the United States was just beginning. Donatila Azacoya Lizarraga was in Merida, Mexico overseeing a large household of children and grandchildren. Did her son, Juan, arrive home that year, either encouraged or forced to leave the United States? Or had he already returned sometime in the decade after he left Muncie? It is hard to tell if he participated in this tragedy or even how his migration affected Donatila's household.

Edith Love Drake was living in Chicago, not far from Indiana Harbor, where the majority of Indiana's Latino households were. Unfortunately, Edith's work with the Traveler's Aid Society did not extend to helping Latino migrants find a way to remain in the United States. Volunteerism aside, in 1930 Edith was preparing for her second daughter's wedding. Like her mother and her sisters, Mary Anthony Drake, had the benefit of an expensive education (at Bennett College in NY) that prepared her for social contributions like fundraising for the Travelers Aid and celebrating the constitution with the Daughters of the American Revolution. To borrow Felsenstein and Connolly's phrase, the metropolitanism, which Edith Love cultivated after her marriage, had deep roots in Muncie. The Daughters of the American Revolution and the Household of Ruth were two organizations that brought women together for civic and social purposes. Although the two groups were kept apart by racist tensions, they shared a belief in the potential of female cooperation and achievement.

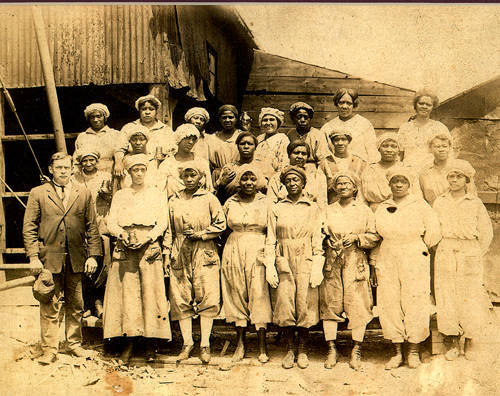

While many things stayed the same outside the factory, the world of commerce and industry was ever changing. At Hemingray Glass Company, from at least 1915 through 1920 African American women worked together manufacturing glass insulators. In the late 1920s it is harder to find them. Whether they were replaced by white women, men or machines, is not clear. Their absence raises questions about the opportunities for working women in the 1930s. As thousands of Hoosier men sought jobs during the Depression, what opportunities remained for Black and white women? By 1929 Mrs. McGuire, the boarding-house keeper, was a widow. She and her husband had sold their boarding house and restaurant decades earlier and left Muncie for Indianapolis. Yet, they soon found that they were back in a similar field running a café and a boarding house. The opportunities for Mattie McGuire had not changed, even in a bigger city.

Following trends across six lives is difficult at the best of times. No trend appears in all lives, but each life teaches something important about the past and how historians investigate. Hopefully, you have found both in this project. If nothing else, the world that they lived in was crowded and productive.