Muncie's Female Glass Workers

In 1886 an Eaton, IN gas field was re-discovered following news of a rich gas reserve opening in northwestern Ohio. Investors flocked to Eaton, only eight miles north of Muncie, and within a few years gas wells in surrounding towns fed dozens of factories and thousands of homes.

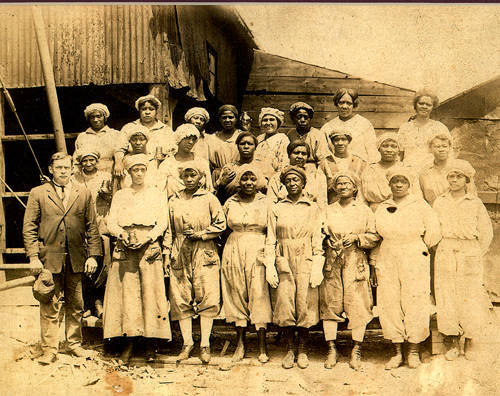

One of the great success stories of the East Central Indiana Gas Boom is the use of natural gas to produce glass products. In Muncie, from 1888 the Ball Brothers Glass Manufacturing Company produced glass jars, while the Hemingray Glass Company molded insulators to prevent electric current loss on open wires. Both companies employed large numbers of workers in Muncie, and became magnets for migrating workers from other states. Yet few historians have investigated the lives of Muncie's female or African American factory workers. This biography strives to identify the women pictured in a photograph, believed to be taken at Hemingray's factory in Muncie around 1915 (below).

This biographical video was researched and created by KJ Amerpohl, Jake Bickel, Caleb Elliott, and Koree Wilson.

The reverse of the photograph (below) is blank. So far no one has identified the twenty-two women and one man in this photograph. It is believed that they worked for Hemingray Glass Company around 1915, based on the insulators that some women hold.

To find women who might have been in this photograph, historians must tred carefully. All conclusions are tentative and must be evidence-based. Charting the rapid growth of the city of Muncie after the discovery of natural gas in 1886-87, historian James Glass noted the early importance of glass factories. Jack S. Blocker has used oral histories to determine what drew migrants to Muncie in the early twentieth century. Repeatedly, interviewees said that reliable work at glass factories attracted their families to Muncie from Upper South states like Kentucky, Tennessee and North Carolina. However, most interviewees mentioned male relatives working at glass factories. This ommission of female workers highlights the importance of this photograph and identifying a little known group of workers.

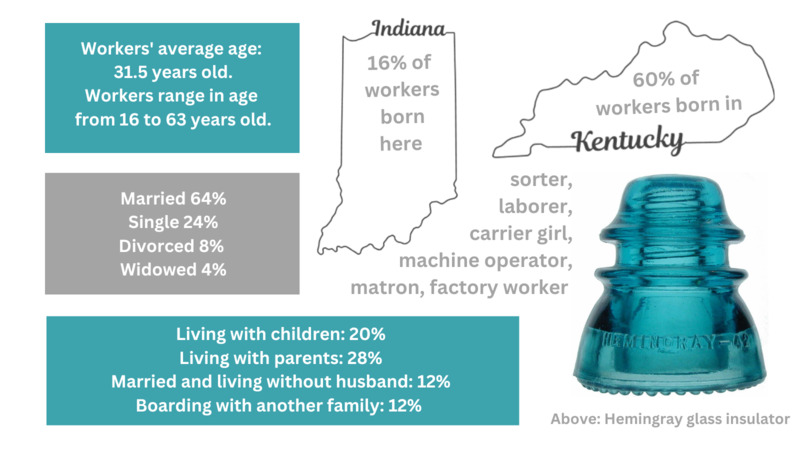

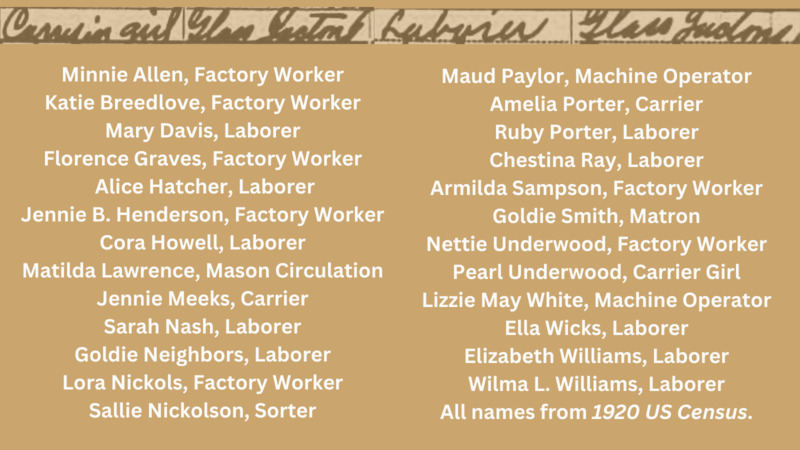

The seventeen women named in the biography video were chosen from the 1920 US Census based on being black women, employed at a "glass factory," and having their residence in Muncie. In 1920 there were eight more women who fell into this category, but who would have been under twenty years old in 1915 when the photograph was taken and less likely to be employed. They were excluded from the video, but have been added to the analysis below, which is based on the 1920 US Census records.

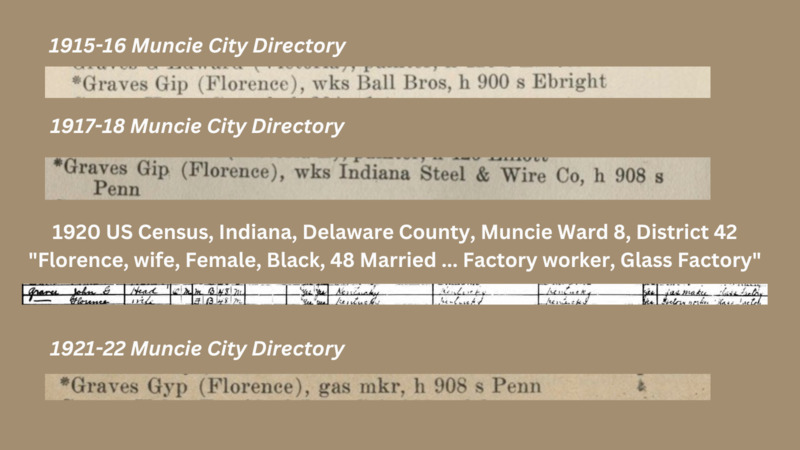

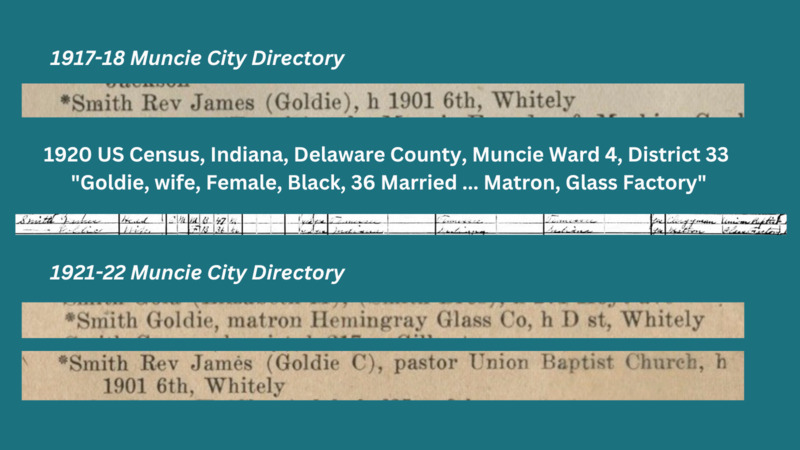

Initially the team looked for female workers in Muncie's city directories. Charles Emerson published directories in 1913-14, 1915-16, and 1917-18, which aligns with the photograph's date. He also published a directory in 1921-22, which supports the 1920 US Census record. Unfortuantely, city directories tend to identify married couples together. Readers see the husband's occupation or employer and only the wife's name. This makes it difficult to determine whether married women worked outside the home.

Below is a series of excerpts from Muncie's city directories for Florence Graves. She always appears with her husband "Gyp" Graves, whose employer changed from 1915 to 1922. According to the limited information in these city directories, implicitly Florence was never employed. Yet the 1920 US Census tells us that John G. Graves was a "gas maker" at a glass factory and that his wife Florence was a "factory worker [also at a] glass factory."

Reading the documents above, it is clear that Florence was employed at least in 1920, and perhaps at other times. The city directories only sometimes identify a married woman's occupation. The excerpt below from the 1921-22 directory suggests that snobbishness about gender and profession combined to exclude most of the female Hemingray glass workers.

Goldie Smith appears in several city directories alongside her husband, James Smith, who was a minister at Muncie's Union Baptist Church. Only in the 1921-22 directory is Goldie listed separately from her husband. The 1920 US Census tells us that Goldie was the "matron" at a glass factory, presumably overseeing other female workers. This position of authority merited its own line in the 1921-22 directory. Notably, women who appear as "laborers" in the Census do not receive the same treatment as Matron Goldie Smith.

To commemorate these women for their labor and achievements, below is the list of Black female glass workers, with their job titles, who the Hemingray Glass Company likely employed in 1920. We hope that some of these women appear in the photograph above, and shared the same pride in the work that made Muncie a famous center for glass production.

Reflecting on historical process is a central part of the historian's work and closely tied to what the historian discovers about the past. Now consider how this project grew from an initial question -- "Who are these photographed women?" -- through the research stage to the creation of a biographical video.

To learn more about how this project came together and uncovered the identities of locally famous workers, watch this methodology video, which was researched and created by KJ Amerpohl, Jake Bickel, Caleb Elliott, and Koree Wilson.

The Town On Fire exhibits define work as labor done for wages outside the home, unpaid chores within the home, and unpaid volunteerism that was freely contributed to achieve community goals. Click on Ida Rickman to learn more about the Household of Ruth, which was one of Muncie's fraternal associations for Black women. Through these groups women worked to shape their communities and fill their social and spiritual needs. These popular activities upheld a widely accepted standard for respectability, which was designed to minimize less desirable behavior. Yet, periodically, this respectable work was undermined by arrest narratives published by Muncie's newspapers. Ida Rickman's biography shows that these two narratives sometimes involved the same people.