Ida Rickman

While one of the historian's central goals is to make known the people that contribute to a community's success, it can be difficult to show a life from different perspectives. We might forget that factory workers had lives apart from making glass insulators. Jennie Henderson hosted the Junior Sewing Circle of the Calvary Church and Armilda Sampson was a member of the Household of Ruth fraternal association. Sallie Nickolson's friends threw her a surprise birthday party and Katie Breedlove moved to Chicago. At the age of only 19, Ruby Porter died, and Goldie Smith's husband, Reverend James Smith conducted the funeral at the Union Baptist Church. These women were industrial workers, but also church and club members, as well as beloved friends and family.

Although she was not a factory worker, Ida Rickman's life had two sides. Alongside the Hemingray glass workers, she participated in the same community groups. Investigating her life juxtaposes this civic involvement with an arrest for illegal alcohol sales. Ida Rickman's biography highlights the public fragility of female respectability.

This biography video was researched and created by Clay Stambaugh, Haylee Drake, Paige Litkenhous, and Madison Yike for HIST 200-01 (Spring 2023) at Ball State University.

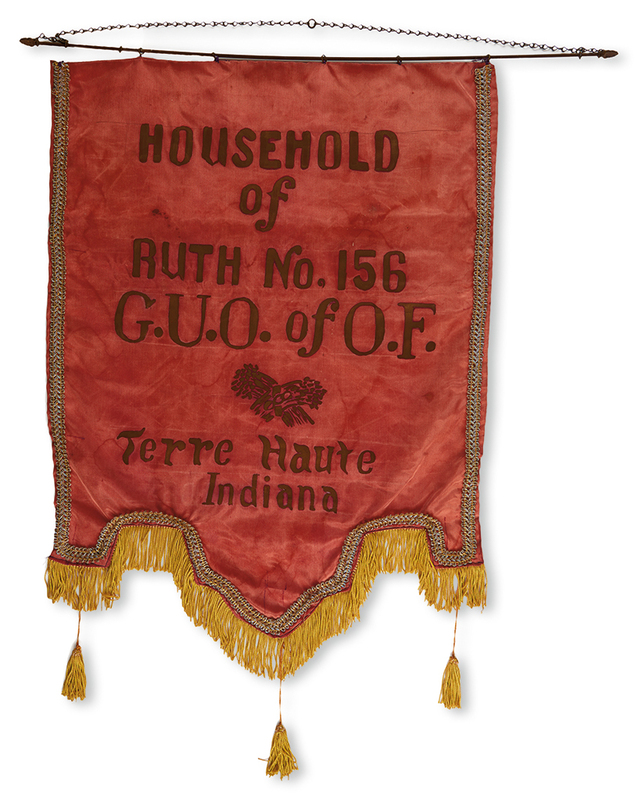

In 1891 a group of Muncie's women established the Golden Link chapter of the Household of Ruth, which is a female auxiliary association related to the African American Odd Fellows fraternal organization.

The Household of Ruth sponsored social, civic, and religious events that provided opportunities to a growing the African American community. This group was part of the wave of women's associations that grew in communities in the second half of the nineteenth century. The first American chapter of the Household of Ruth opened in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1858. By 1890, Indiana hosted chapters in Indianapolis, Evansville, Richmond, and South Bend. As Jack Blocker reminds us, between 1890 and 1900, Indiana's Black population grew by 12,000 people (i.e., more than 25%). Some of these citizens joined new chapters in Fort Wayne, Logansport, Boonville, and Rushville that opened by 1910.

Below is a photograph from Evansville, IN in the 1930s, of members of the Household of Ruth alongside their Odd Fellows counterparts.

Although once thought to be invisible to historians, fraternal organizations flourished in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Migration of African Americans from the American South to the North added to fledgling Midwestern chapters. Newspaper articles provide frequent accounts of their activities. Readers can see how women cultivated religious community, encouraged 'respectable' social events, and gained leadership experience.

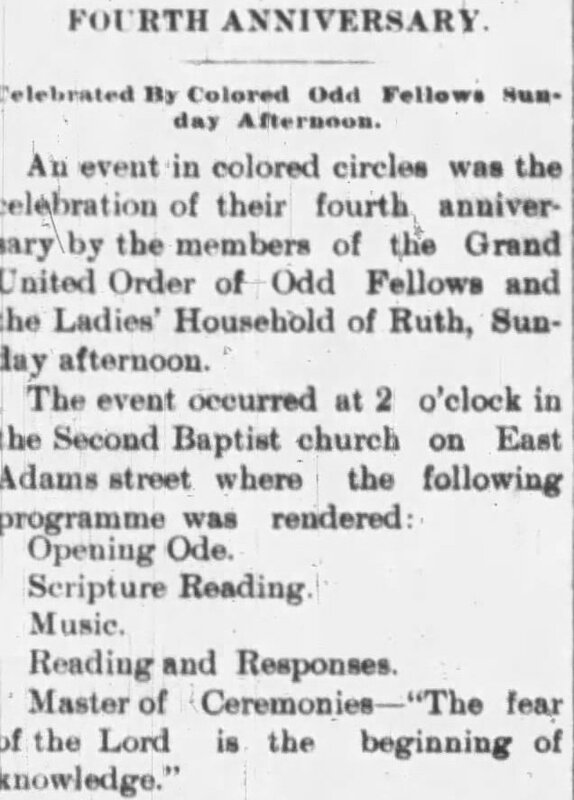

As Anne Firor Scott noted in her article "Most Invisible of All," "the church was so central an institution in the emerging black communities, that there was never a clear line between church-related and secular associations." This is plain to see in the newspaper account of the Muncie chapter's fourth anniversary celebration (left). Not only did the event take place on a Sunday in the Second Baptist Church, but it opened with a Scriptural reading. In a similar way, the Odd Fellows celebrated their organization's anniversary at the AME Church with a performance by the Eagle Band, which was a local favorite.

Many of the presentations (not shown) were sprang from biblical passages, including "Whosoever hear my voice will dwell safely" (Proverbs 1:33) and "Cast in thy lot among us, let us all have one purse" (Proverbs 1:14). These passages also emphasize the mutal help and communal security that characterized both church congregations and fraternal organizations.

As Muncie grew by absorbing new residents, many of whom worked in factories attracted by the Gas Boom (1886-1900), fraternal organizations offered social events where young and single people could meet, chat, and dance in a public, supervised place. A newspaper article from 1892 (left) recounts a party sponsored by the Housheold of Ruth. It was held in the organization's rented rooms at West Main and South Walnut Streets, a busy downtown location next to the Opera House. The event was semi-exclusive, in that it was open only to Household members and their guests, but undoubtedly 'respectable.' We can imagine how the cake and ice cream, and the assurance that "a splendid time was enjoyed by all present," acted as an advertisement for the Household and its brother organization, the Grand United (sometimes Improved) Order of Odd Fellows.

"Notice," The Muncie Daily Times, August 4, 1894.

"Resolutions," The Muncie Morning News, March 1, 1899.

Like all other fraternal organizations and clubs, the Household of Ruth had an organizational structure of officers and committees. Members elected the women who served in these roles annually. Announcements appeared in local newspapers reminding members to attend meetings and vote in elections. In 1894, Flora White and Lenora Ellis reminded their fellow members of this duty (left). The women who served in the highest offices represented their chapter at the Household of Ruth's annual state convention. In August 1896, Flora White traveled to Gallesburg, Illinois to attend the Grand Lodge meeting of the Order of Twelve, which was related to the Order of Tabor, another fraternal organization. Three years later, Flora White died of stomach troubles.

The "Resolutions" committee was responsible to acknowledging this loss publicly and sharing information among members. These officers, Ida Rickman, Anna Strowthers, and (another notable woman) Josephine Jones Pierson, conveyed the Household's condolences to her family in print (left). This organizational work knit the community of women together through a shared social network, Christian faith, and public acts.

These newspaper articles from the 1890s stand in stark contrast to the announcement of Ida Rickman's arrest in 1909. How do we reconcile the Household of Ruth with the accusation of illegal alcohol sales and brothel-keeping? In September 1908, Delaware County voted to close its saloons and prohibit commercial sale of alcohol. In December 1909, Ida and her son Orville Haines were arrested "in a house of ill repute" for selling liquor without a license, after their home was raided. They pleaded not guilty. Constables confiscated two jugs of whiskey, which Ida and Orville claimed for for their own consumption. Looking at the map below, we can see twelve of the other thirteen locations raided at the time of Ida and Orville's arrest. Most were commercial operations run by white men (former saloon proprietors) that were spread across the city.

When the case came to trial a week later, the charges against Ida and Orville were dropped due to absent witnesses. The Muncie Evening Press reported that the court expected a strong case, and re-arrested Orville only hours later. Again Orville pleaded not guilty. The Muncie Evening Press wrote that the charge was a long time coming as it was commonly thought that the Haines household was selling liquor to their African American neighbors. At trial witnesses stated that Orville had served them whiskey at his home. He was convicted of selling liquor without a license, fined $70 and sentenced to sixty days in jail. As the article (left) notes, Judge Gass suppressed Orville's jail sentence for the sake of racial equality.

There is little evidence of the arrests' specific impact on Ida. She does not appear in Muncie's newspapers again after 1909. The reference to running arrested at "a house of ill repute" at 402 Kirby Avenue is curious. The charge was withdrawn, but it was not the first reference to sex work. In July 1894, The Muncie Daily Times reported that Ida Haines, a housekeeper in Lulu Shoemaker's brothel, had overdosed on morphine. This woman seems to be a far cry from the woman who joined the Household of Ruth, yet historian Catherine Carstairs reminds us that the media portrayed African Americans in this period as more likely to be involved in drug use, crime, and violent encounters, obscuring the truth with stereotypes. These stereotypes persisted in spite of the civic contributions of fraternal orgamizations that appeared in the same newspapers. With only newspapers to rely on, Ida's life story twists and turns prompting more questions about Muncie than we can answer.

A year after the arrest, Ida's husband, Daniel Rickman was living with his mother and nephew at 801 South Vine Street. Although the 1910 US Census listed Daniel as still married there was no sign of Ida. In 1923 he married a woman named Josephine. The couple had two daughters, who married the young Goodall brothers. Orville had married Biddie Petticord in 1906, and the 1910 Census shows them living on West Charles Street with her parents. Ironically, their next-door neighbor was Anna Augusta Truitt, another notable woman, who had served as the president of Women's Christian Temperance Union in the 1890s.

To see how this project came together with some surprises along the way, watch this methodology video, which researched and created by Clay Stambaugh, Haylee Drake, Paige Litkenhous, and Madison Yike.

Click on Mrs. Mattie McGuire to see how respectability was a central criteria for women's work and social status. As Ida Rickman's biography suggests, financial stress could temporarily displace respectable work, but church membership and fraternal organizations could rebuild that status. Boarding houses were one of the contested sites for nineteenth-century female respectability. Mattie McGuire's biography reveals the challenge of running a boarding house in an expanding city with a large temporary population.