Hallie Shaffer

Hallie Shaffer reminds us that every day black and white Hoosiers interacted at school, at work, on the streets, and in households. Rarely did they interact in full equality, but their presence together was a start. While some notable women lived in predominantly or exclusively white neighborhoods, like Riverside, many other people lived or worked in areas like the Southside that had a greater integration of black and white citizens. Muncie's commercial center was inhabited mostly by white residents, but many black workers owned or were employed by local businesses. Black and white Munsonians would have worked together, spoken daily, and often shared similar goals.

Unfortunately, the state was slow to reflect this overlapping experience. By the 1890s Indiana had come a long way from the 1851 Constitution that forbade black or bi-racial people to settle in the state (Article 13), but it still had a way to go. From 1886 Muncie's industrial growth depended on the arrival of new workers, and as Jack Blocker has noted, in the following years the black population grew at a faster rate than the white population. While the city's success was built on its willingness to employ black workers, it was not willing to embrace bi-racial marriage. First introduced in 1818 and then reinforced in 1840, the law forbidding interracial marriage was not repealed in Indiana until 1965.

The life of Hallie Shaffer helps us think more about interracial relationships, the way that class defined (unattainable) expectations for women, and possible mental health impacts. While these are all issues commonly discussed in the twenty-first century, they were far more controversial in the late nineteenth century.

This biographical video was researched and created by Sophia Halfman, Halle Pressler, Mari Guerra-Uribe, and Samantha Tarapore.

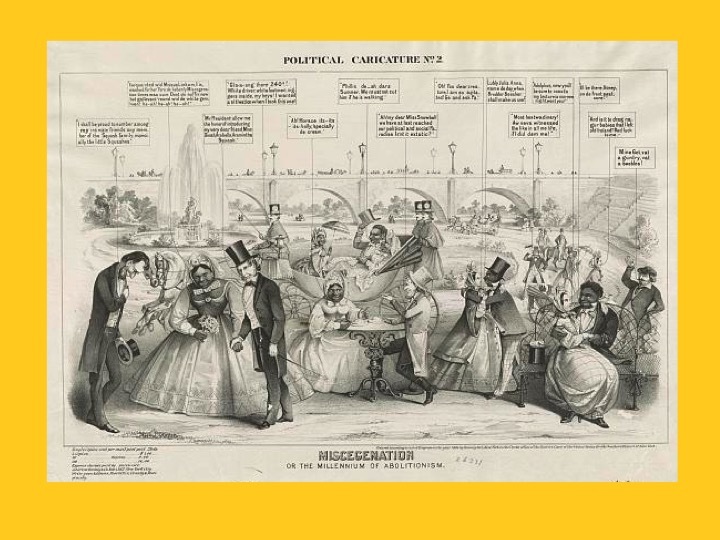

Miscegenation was only one issue related to race relations, but in the second half of the nineteenth century it captured the public imagination. During the presidency of Abraham Lincoln (1861-64), G.W. Bromley & Co. produced a series of satirical engravings that imagined the results of the abolition of slavery and racial equality. Below is one engraving, which presents elite white male politicians calling on black women. The women's speech suggests that they have recently moved from the washhouse to the parlor, and was intended to emphasize the ridiculousness of equality between men at the top of the social hierarchy and women near the bottom.

Above: G.W. Bromley & Co., Miscegenation or the millennium of abolitionism (1864)

More chilling to white observers was the possibility that white women might marry black men. Generally contemporaries feared that white women would be forced into these relationships, which were insultingly described as "unequal unions." Beyond citing the couple's arrests, newspaper descriptions of the Shaffer-Walker wedding do not sound an alarm as we might expect. The answer likely lies in their low social status.

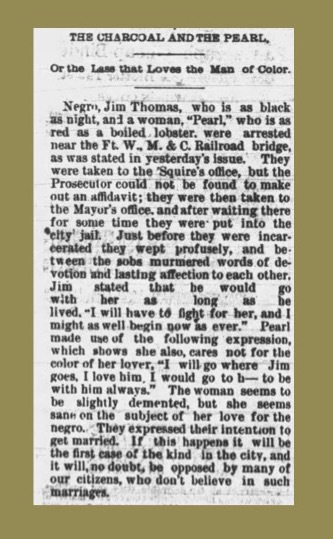

Hallie Shaffer was not the first white woman in Muncie to wed a black man. In 1881 Pearl Stevens and Jim Thomas were arrested on charges of associating (with intent to prostitute). A Muncie Evening Press article (left) made much of their racial difference, calling them "The Charcoal and the Pearl." The article paid close attention to their romantic speech, and concluded that "the woman seems to be slightly demented, but she seems sane on the subject of her love for the negro." Although there was no malice in the account's description, beyond its misogyny, it did predict the city's disapproval. The race of the disapprovers was not noted, and sure enough when the couple married they were arrested. As with Hallie Shaffer and Jim Walker, the relationship formed between a white woman accused of sex work and a black working-class man. Neither couple was wealthy or occupied a socially elite position. The result was the (white) newspaper's condescending tone and an expectation that the law would not allow their union.

Soon after their arrest in February 1896, the Muncie Daily Times reported a meeting in Indianapolis to organize a repeal of the state's miscegenation law. The Booker T. Washington Literary Society, meeting at the Blackford St. African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, struck a committee to lobby each candidate in the next legislative election to support the law's repeal. Notably, while many meeting attendees did not support interracial marrigae, they were offended by the law's racist restriction.

The newspaper account of Pearl Stevens' arrest reinforces the idea of women as emotional and romantic beings, whose well-being was more closely tied to relationship success than men. As Howard Kushner's research shows, women were routinely described as committing suicide due to failed romances. However, the mostly male journalists who composed these accounts lived far away from the financially precarious world of most single or independent women. Their emphasis was on morality and actions, rather than on how society's expectations might lead to marginalization and poverty.

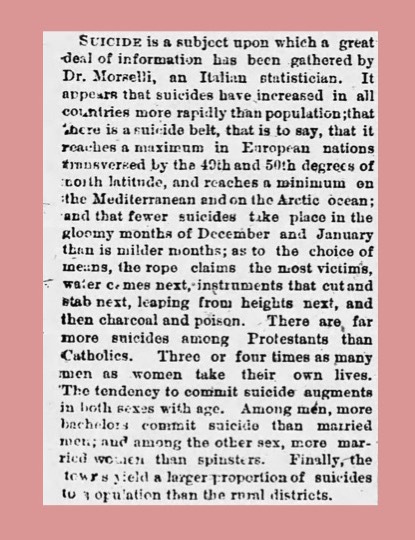

In the early 1880s there was discussion in Hoosier newspapers of a Suicide Belt that ran through Indiana based on the state's high number of cases. Interestingly, in 1879 an article in The Muncie Morning News asked whether Hoosiers were growing more despondent as the state grew more prosperous, leading to a higher suicide rate. There was no answer to the question, other than a reminder that "the majority of newspaper readers crave that class of reading matter or the press would not be encouraged in publishing it."

Reading newspapers from the 1880s and 1890s shows a continued interest in both sex workers and their emotional lives. Suicide was an unfortunate end for several women who worked in Muncie's brothels. In lieu of a greater physical memorial, here is a list of women, drawn from Muncie's newspapers, who took their own lives amid difficult circumstances.

Flora Hines, February 1881

Nellie Linville, August 1897

Ida Lutz, November 1898

As the newspaper account (above) indicates, research on suicide was growing in this period and met a lively readership. Unfortunately, there was still little discussion in newspapers of how to prevent suicide.

To hear more about the historian's process and the methodologies used to research and create historical narratives, check out the conversation between Sophia Halfman, Halle Pressler, Mari Guerra-Uribe, and Samantha Tarapore below.

Not all independent or working women turned to vice activity, although through its boom town period (1886-1900), Muncie had a surprising amount of it. Many women worked in factories, households, and the downtown commercial core. Click on Maggie Morin and Belle Davidson to learn about two female entrepreneurs whose businesses catered to the female economy. Hair stylists, dressmakers, and milliners were important fashion and social brokers, whose work ensured that they were well known across the city.