Julia Coleman

Julia Coleman was born in 1862 in Washington, DC and died in 1919 in Muncie. Her life reflects the intersection of many conversations from the post Civil War period. As an African American, she grew up in a period of uncertain civil rights. As a migrant to Muncie, she and her family moved to a Midwest industrial community to support its workers. As a woman, she served as a wife, mother, church leader, clubwoman, and community organizer in the period before women could vote in most civil elections.

Like many other women of her time, in life her influence and skills were substantial, but in death her local legacy is sometimes forgotten. Julia Coleman's experiences remind us of how women impacted their communities through churches, clubs, families and otherwise, in ordinary and essential ways.

This biographical video was researched and created by Kathleen Donoho, Katrina Partlow, Sam Kidder, and Kayla Riddell.

As Thomas J. Ward reminds us in his research on black physicians, membership in the African American professional class depended on education, wealth, and independence from white society. Physicians, ministers, and lawyers were at the top of the heap, followed by business-owners and teachers. Ministers were often educated and as church leaders they were free from white professional control. Julia Coleman and her husband Martin, a minister at Muncie's Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, offer an example of a black professional household.

Above: Bethel AME Church and Parsonage (built in 1914)

The Other Side of Middletown Photographs, MSS.254

Ball State University, University Libraries, Archives and Special Collections

Although both Julia and Martin were educated and influential members of their community, they were not wealthy. In 1910 the couple and their two children lived in an apartment (and later the new parsonage) at the church site. This building was torn down in the early 1980s, and the current church stands in its place.

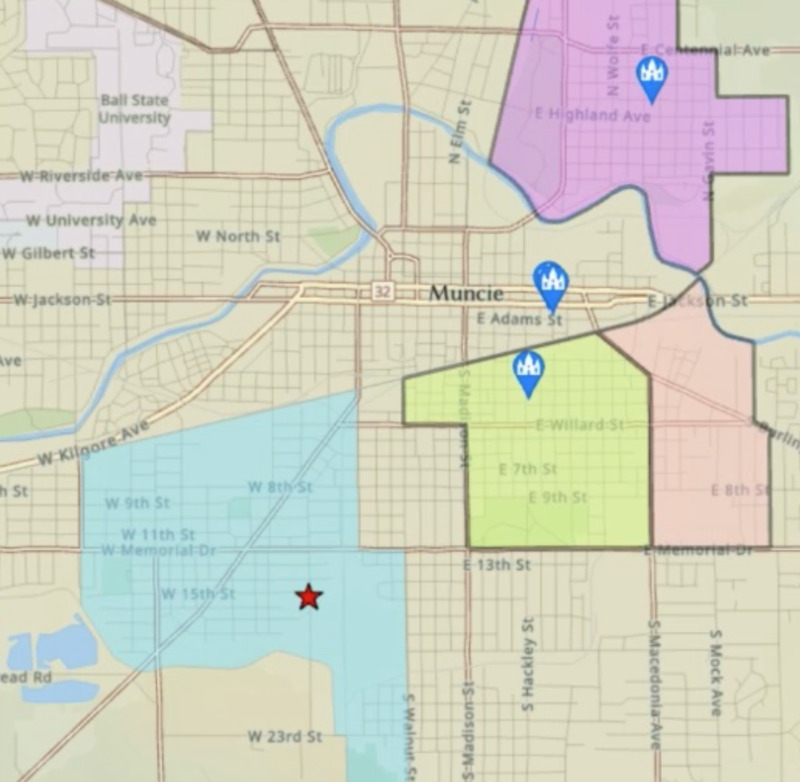

Later, perhaps after Martin retired as full-time minister, they moved to a house on South Gharkey Street. As the map below shows, their home was on the edge of Shedtown (now called Avondale), a poor neighborhood south of Memorial Street and north of 17th Street. The two-mile trek to Bethel AME on East Jackson Street took them through the Southside neighborhood, which was home to much of Bethel AME's working-class congregation.

Studying Muncie’s black and white populations together is essential, but difficult. Robert and Helen Lynd, the sociologists who wrote Middletown: A study in contemporary American culture (1929), ignored Muncie's vibrant African American community. They preferred a racially and culturally homogenous population and down-played the city's diversity and the challenges that came with it.

Throughout the period of 1870-1920, Muncie’s population grew from about 5,000 to 36,524 people, and was overwhelmingly white, Protestant, and native born. In 1920 there were several hundred immigrants, small communities of Jews and Catholics, and 2,054 African Americans (5.4%). While in many parts of the city black and white Munsonians lived as neighbors, there were still economic and social disparities that signal continuing inequality of resources and opportunity.

While Muncie’s schools were integrated, segregation existed in churches, parks and theaters, and in community services. African American churches became hubs for communal support, and developed resources that the white population refused to share. Equalizing the black and white populations and breaking down barriers was a core part of the AME church’s mission. As a minister’s wife, Julia Coleman was expected to be an active organizer, both because she was well known through her husband’s work and because her care for the community was part of this position.

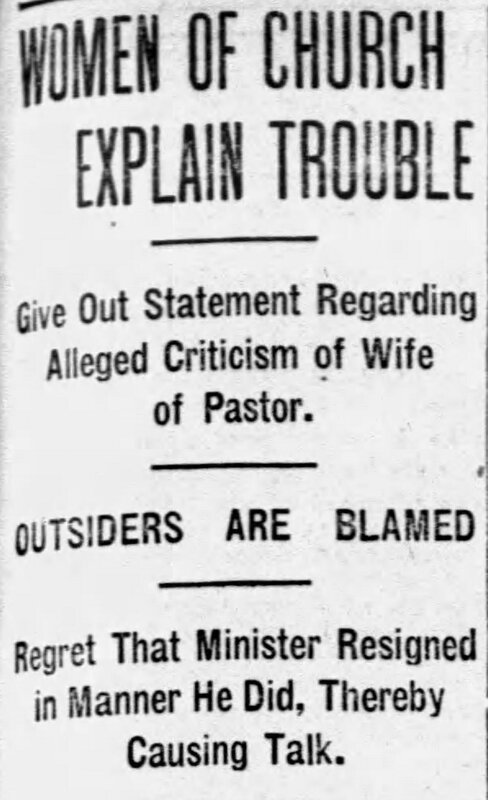

As many modern observers have noted, being a minister’s wife is another example of unacknowledged and often unpaid labor. While Julia lived in Muncie The Star Press (1906) reported that Rev. Clewes of Fairmount, IN had abruptly resigned his position at the Congregational Church after criticism of his wife. The line between employee and long-suffering neighbor blurred with the minister’s wife, who was often subject to expectations that were inconsistent with her household's wealth and human nature. Sadly, there are few records of Julia's thoughts, but many examples of her constant community volunteerism.

To hear more about the historian's process and the methodologies used to research and create historical narratives, check out the conversation between Donoho, Partlow, Kidder and Riddell below.

Click on Genevieve Hanna to learn more about how another educated woman contributed to Muncie. Genevieve was the daughter of a white Presbyterian minister Lyman Hanna, and never married, yet she likely grew up in a household that was culturally similar to Julia Coleman's. See how Genevieve's contribution extended the ideal of community-building that Julia Coleman lived by.