Maggie Morin and Belle Davidson

As this project shows, women worked in a variety of industries, legal and illegal, commercial, industrial and domestic. Maggie Morin and Belle Davidson present an important aspect of Muncie's commerce: the female economy. This was a portion of Muncie's commercial activity that specifically catered to women and their needs. The female economy was often run by women for women, but not always. Exploring Morin and Davidson's careers show how business women and female labor was an important part of Muncie's success.

This biographical video was researched and created by Courtney Cherepski, Lucas Freeman, Mya Jenkins, and Makenna Poindexter.

Maggie Morin and Belle Davidson: Notable Muncie EntrepreneuHERS

As Wendy Gamber's research shows, in Gilded Age and Progressive Era literature women seeking work often did so following a family death or disaster. With their social position in jeopardy, they sought a job that would maintain their respectability. In novels from this period, many of these women either experience social decline -- fall from the professional class to the working class -- or are saved from poverty by marriage. Few women in contemporary novels became successful businesswomen, unlike in real life.

The Notable Women Project has shown that in Muncie there were many women who worked for wages and they were not clustered in a single class. Dr. Anna Lemon Griffin was a physician. Alfaretta Poorman Hart was a police matron and later ran a bank. Cornelia Frazier worked in a hotel laundry, and Carrie Gillenwaters was a domestic servant. Some women worked along side their husbands: Lee See Chin operated a Chinese restaurant and Sallie Harris Herrmann ran a millinery and fancy goods store. Work was an essential part of life and just like today, many women found it fulfilling.

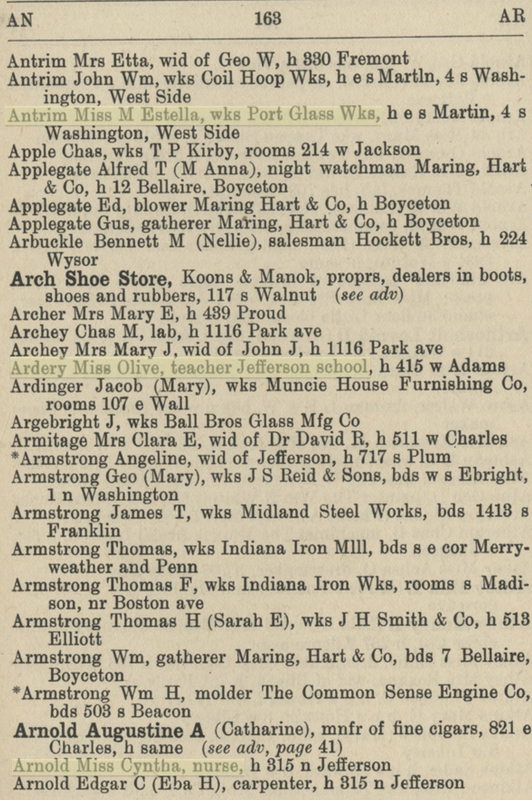

Above: 1893-94 Emerson's Muncie City Directory, p. 163

The Muncie city directories provide a more detailed snap shot of working women in this period. Printers issued these documents every few years to serve as a directory of residents, businesses, telephone numbers, and civic institutions. Examining the 1893-94 Emerson's Muncie City Directory illuminates several conclusions. First, women worked in a wide variety of fields, but they clustered in several particular jobs, inlcuding compositors (at newspapers), domestic laborers, dressmakers, milliners, and tailoresses, laundry workers, sales and shop clerks, stenographers, teachers, and waitresses. As in the twenty-first century, in the 1890s women often worked in the service industry, and in a few factories including the Tappan Shoe Factory, Muncie Skewer Company, Ball Brothers Glass Company, and the Muncie Glass Company.

Second, most women listed in the 1893-94 directory as working outside the home were unmarried. Many women appeared as "Miss" and a very few as widows. The directory's custom of listing couples according to the husband's name and profession, suggests that all married women worked in the home this was not the case. Some of these wives worked with their husbands in the family business. Often their sons and daughters were listed separately according to their role in the business. Some women worked with their sisters in the same shop or factory. Married women who worked beyond the family business can be hard to track, but not impossible.

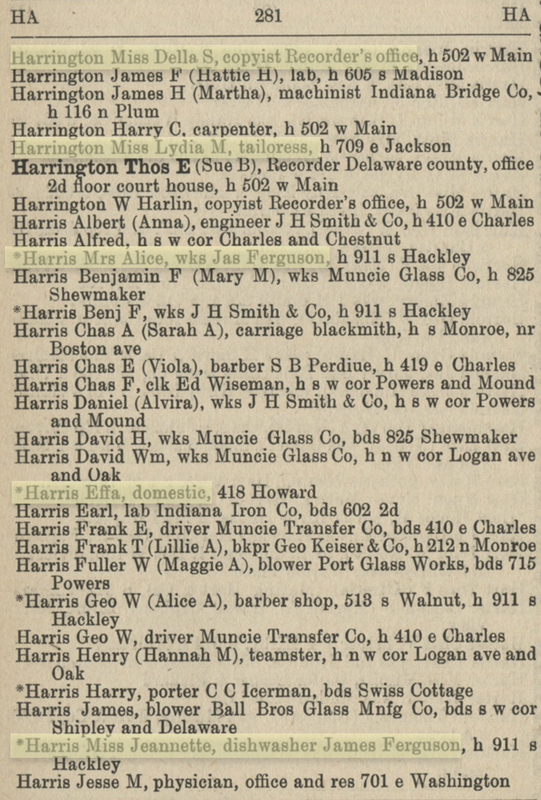

Above: 1893-94 Emerson's Muncie City Directory, p. 281

Third, women who performed unofficial or illegal labor do not appear in the directory. Women who tended market gardens or preserved fruits and vegetables for sale are not listed. Women who operated streetside lunch stands or a take-away counter from their homes are not listed. Women who cared for their neighbors' children as well as their own are not listed. Much of the work that women performed using household skills, which supported their households, does not appear in the directories because it did not occur in a licensed or public venue, even though the income was essential.

Fourth, most of the female workers listed in the directory are white. The female working population reflects the city's larger population division: 95% white and 5% black. White women do the same jobs as black women, particularly laundry workers and domestic servants. However, as the directory page (left) shows, black women were disproportionately present in these fields, while white women are employed across the labor spectrum.

As there were few black high school graduates living in Muncie in 1893-94, perhaps the 1903-04 and the 1913-14 directories present a different story.

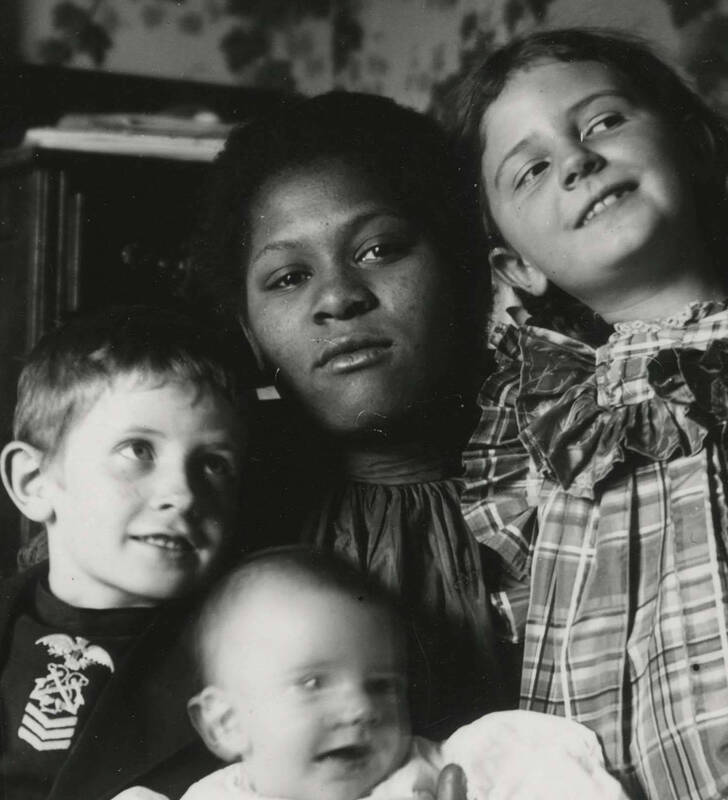

Above: Carrie Gillenwaters and the Ryan-Marsh children. Photograph by John Rollin Marsh, Marsh-Ryan Family Collection, M-369, Archives and Special Collections, University Libraries, Ball State University.

Finally, while the city directory tells us a lot about unmarried women, it provides few answers about widowed women. The frequent inclusion of Miss or Mrs. or "widow" in the directory signals many women's marital status. Readers today might find that odd, but it was an important indicator of whether a woman needed to work. (Divorce also impacted women's financial situation, but it is trickier to see in the city directory.)

Reading the city directory shows how many widows lived in Muncie in 1893-94. There is still a great deal of research left to uncover how widowed women (usually older) made a living. Most of these women appear without a profession listed. How did they pay the bills? Did they live with their working children as Carrie Gillenwaters' (left) mother Leanna did? Did they contribute to their children's business? Did they work unofficially or want to appear publically to be at leisure? How did race play a role in this discussion?

To hear more about the historian's process and the methodologies used to research and create historical narratives, check out the conversation between Cherepski, Freeman, Jenkins and Poindexter below.

While unofficial or private labor can encourage some female workers to go undocumented, sometimes labor related to religious communities is disfficult to disentangle from devotional activities. As a minister's wife, Julia Coleman is an example of the overlap between work and worship. For another example, click on The Nuns of St. Lawrence School to learn about the working women who supported Catholic devotion and education in Muncie from the 1880s.