Introduction

"We are justified in believing that the success of this movement for equality of the sexes means more progress towards equality of the races."

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, “Trust the Women!” The Crisis 10, no. 4 (August 1915).

Warning: Undefined array key "imgAttributes" in /home/digita63/public_html/notablewomen/plugins/ExhibitBuilder/views/helpers/ExhibitAttachment.php on line 30

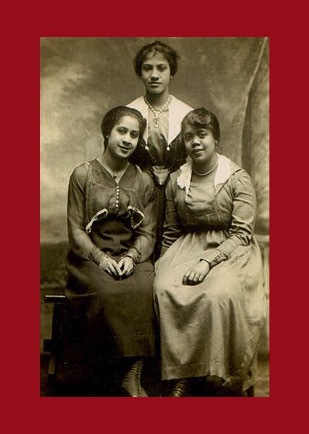

In 1894, the same year that Maggie Morin’s son John graduated with honors from Muncie’s high school and around the time that Hallie Shaffer met James Walker, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin launched a monthly newspaper written for and by black women. Called The Women’s Era, it ran from 1894 to 1897 and was distributed nationally. Published in Boston, the newspaper was unapologetically feminist and collegial. The newspaper’s slogan was “Help to make the world better” and the front page reminded readers that it was “devoted to the interests of the women’s Clubs, Leagues and Societies throughout the Country.” To this end, the newspaper focused on education, suffrage, anti-lynching, and other reform and race-relations issues. While it is hard to know if any Muncie women had a subscription to The Women’s Era, they were precisely the readership that Ruffin targeted.

From the 1880s, Muncie’s black community hosted numerous clubs and associations for women. These existed in addition to the auxiliary groups related to fraternal organizations, like the Household of Ruth and the Order of the Eastern Star. Like their white neighbors, black women often expanded their civic involvement through clubs sponsored by their churches.

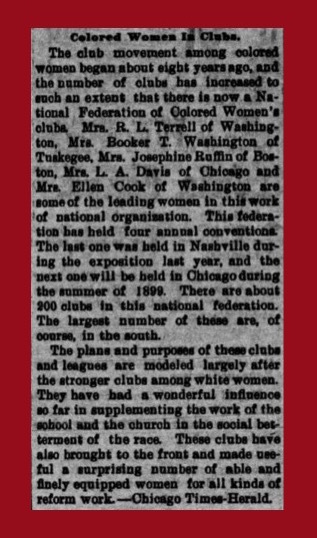

In 1898 the Muncie Evening Press reprinted a short column (originally from The Chicago Times-Herald) reflecting on the black women’s club movement and the National Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, led by Ruffin among other women. Rather condescendingly the article noted that black women’s clubs had much the same goals and plans as white women’s clubs. While congratulating the club members for their achievements, implicitly the article emphasizes how far America was from achieving Ruffin’s goal of “equality of the races.” Perhaps a more impressive achievement was that black women were active club members in spite of the fact that they more often worked outside the home and in households with lower average incomes than their white counterparts. Although black clubwomen had less money, a smaller population, and greater legal uncertainty, their club life had an equal impact and importance.

When evaluating the extent of the American club movement in 1899, Ellen Martin Henrotin, a Chicago-based social reformer and president of the General Federation of Women's Clubs, enumerated the thousands of American clubwomen. The Muncie Morning News asserted proudly that “there is hardly a Hoosier county seat without half a dozen women’s clubs.” But how many of them included black women? How many included working-class women? How many clubs embraced women of all races, religions, and classes? The careful historian will say that it is difficult to know, because the records that survive mostly come from white women’s clubs, which operated in communities that developed connections with archives.

Once again Town On Fire strives to shine a light on women often forgotten. The six biography videos that follow explore the lives of women living in Muncie between 1870 and 1920. They came from across the country, and represent different races, income levels, and religions. Their experiences tell us more about the struggles faced by Muncie’s women to make their way in an uncertain world. Not all the women were club members, but they all benefited from Ruffin’s work to empower women.

To learn more about women in Muncie's AME Church and the club movement, click on Julia Coleman. Her position as a minister's wife meant that she was well-known, always under scrutiny, and expected to be a model for other woman.