Conclusion

As the Introduction to this exhibit states, nobody in 1900 took a photograph to show the realities of a woman's life in the service industry. Most photograhers took photographs to document goods in an attractive store, or to advertise a business. Understanding this documentary impulse is important, since it helps us investigate the working lives of past men and women.

Above: Photograph of women's hat display at McNaughton's department store in Muncie (1925) by W.A. Swift. Ball State University, Archives and Special Collections, W.A. Swift Photographs Collection, P8-0276.

The photograph on the left is a good example of surviving images of women's work environments. We see a display of women's hats from 1925, in the McNaughton department store that stood on the southeast corner of South Walnut and South Charles Streets. As Wendy Gamber and Theresa McBride reminds us, women who worked in shops fulfilled an important middle-class role that was indoor and protected from the elements, demanded field-specific knowledge, and a clean and civil demeanor. The women who worked in the McNaughton millinery department were a valuable part of the city's commercial enterprise and interacted with women from diverse classes, races, ethnicities, and neighborhoods.

This photograph shows the space and tools of work, allowing historians to imagine the bustle of clerks and customers and the sound of conversation and cash registers. However, like other photographs, it is empty of female workers. We must imagine the gender, age, race, and appearance of both workers and customers, as well as managers. Unfortunately, these absent details are crucial to understanding the dynamic interactions that took place in shops, restaurants, hotels, hospitals, saloons, and factories.

Above: Advertisement for the store run by Isabelle Prince Leon and her husband, The Muncie Morning News, June 25, 1895.

The advertisement for the Leon's store (left) is an example of the primary sources that remain for women's lives in Muncie. They tend to be textual (made up of words), rather than visual (made of images). They tend to tell us about the world of women and their husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons. It can be difficult to separate a woman's experience from the men who surrounded her. In this way, a project investigating Muncie's women is really investigating life in Muncie.

The primary sources also vary depending on race and class. As the previous exhibit pages have shown, black-owned businesses were harder to research, than white-owned businesses. They served a smaller community and seem to have a higher turn-over rate than white businesses. While this makes them a more difficult focus for historians, it does not reduce their importance.

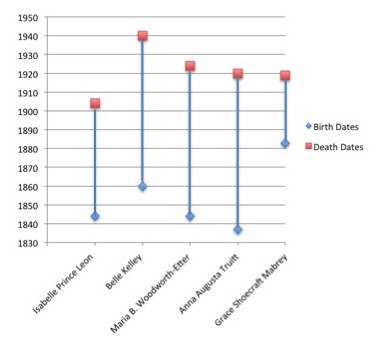

Above: a graph showing the life spans of all five notable women profiled in this exhibit (1837-1940 CE).

As the graph (left) shows, all five women profiled in this exhibit were in Muncie for short or long periods during the 1880s and 1890s. This was the time of the East Central Indiana Gas Boom (1886-1900), when factory-owners took advantage of cheap natural gas and a growing stream of migrant workers. From 1880 to 1900, the city's population grew from 5,000 to 21,000 and its commercial and industrial activity exploded.

In the course of this urban growth spurt, Muncie's paper trail expanded. A larger population could support more daily newspapers. As more factories and shops opened and workers arrived, city directories were compiled more frequently to ensure accuracy. As the city's commerical and residential infrastructure grew in wealth and size, Sanborn fire insurance maps expanded from three sheets (1883) to thirty-seven sheets (1902). Finally, with urban growth came administrative increase. This is seen in more detailed death certificates and census records, longer arrest and trial records, and a higher survival rate of documentation over all.

The increase of documentation from the 1880s onward is important as it provides a counterweight to what is missing from photographs. Holes might still remain, like the 1890 US Federal Census lost in a fire. Yet assembling multiple documents as this exhibit does, can reveal lives otherwise lost. Together visual and textual sourecs help us piece together the world that these five women lived and worked in.