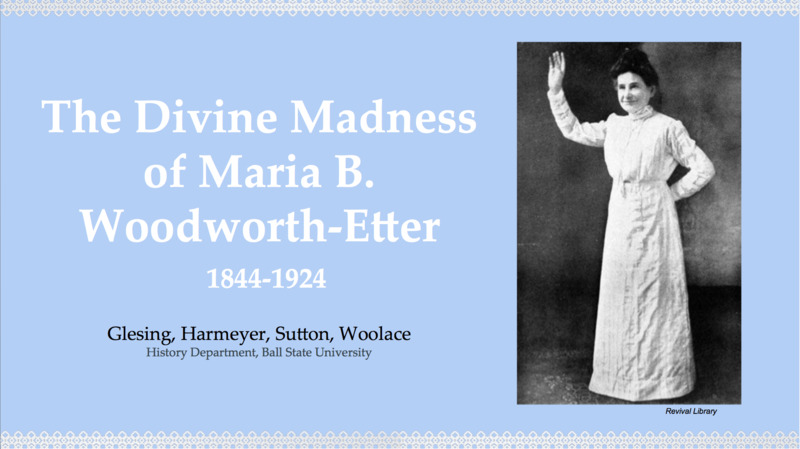

Maria B. Woodworth-Etter

Unlike the other women profiled in this project, Maria Woodworth-Etter was not a resident of Muncie. Instead, she visited in 1886, 1890, and 1893, setting up a revival church that weathered criticism and satire from local newspapers. For several weeks Woodworth-Etter, a handful of other preachers, and her assistants set up their church in the fairgrounds under a big tent that followed the "kerosene circuit." Moving from town to town across the Midwest from the mid-1880s, Woodworth-Etter's church was transient and her congregation was self-selected. Her experiences in Muncie and elsewhere, reveal a great deal about how late nineteenth and early twentieth-century contemporaries envisioned and experienced churches.

This biography video was researched and created by Payton Glesing, Nikki Harmeyer, Jordan Sutton, and Caleb Woolace for HIST 200-02 (Fall 2022) at Ball State University.

In 1922 when Muncie's Jewish community moved into their new synagogue on West Jackson Street (see below), the facade was engraved with the words: "Mine house is a house of prayer for all peoples" (Isaiah 56:7). The congregation had been fundraising for two decades and first purchased a site at Jackson and Madison Streets in 1903. The newspaper announcement stressed the "commodius and beautiful house of worship" that would result.

Other congregations in Muncie worked hard to construct church buildings that could embrace a growing population and dynamic leadership. In 1912 the Bethel A.M.E. Church (see below) farther east on Jackson Steet began to remodel the parsonage where the pastor and his family lived. Julia Coleman and her husband Pastor Martin lived here with their children. Through the year there were fundraising suppers and periodic reports of the progress of painting and varnishing. These reports show the congregation's pride in church buildings and their investment and interest in the physical space.

The impermanence of revival churches were part of their advantage. They could go where the people were and move on when the community lost interest or the weather changed. Over the course of her career, the support structure that underpinned revival churches changed dramatically. In 1918, after nearly forty years preaching, she settled down and opened the Woodworth-Etter Tabernacle in Indianapolis. Yet in the first decade, Hoosier newspapers viewed revival meetings, and Maria B. Woodworth-Etter in particular, with skepticism.

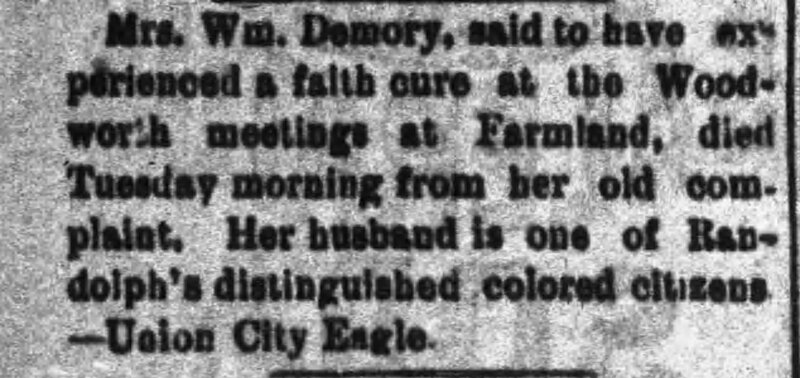

In 1886, The Indianapolis Journal published a letter signed by "One Hundred Church Members" expressing the "gravest apprehensions" and asking her to cease preaching and leave the city. In 1887 The Muncie Morning News printed a death notice for Mrs. Demory of Union City (left), noting that she had died of the complaint that Woodworth had supposedly healed.

Below is a photograph of the entrance to Woodworth-Etter's revival tent.

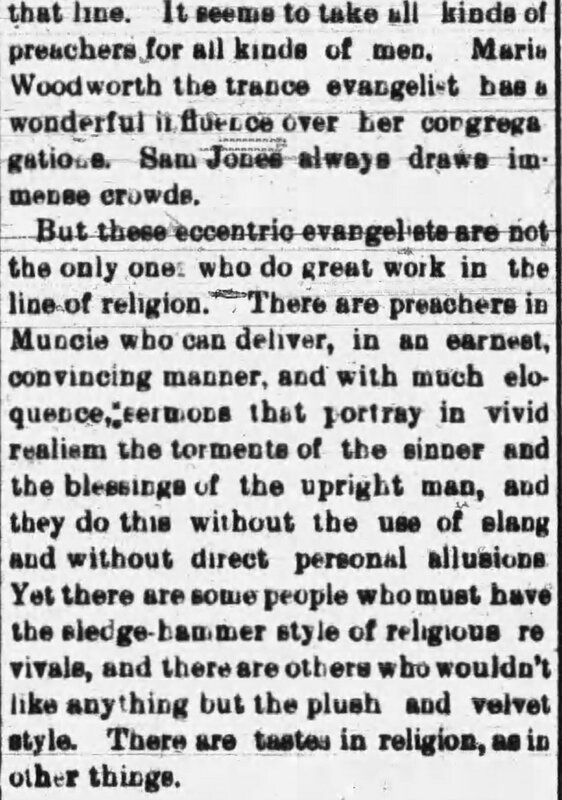

In a surprisingly balanced evaluation of the religious landscape, a reporter at The Muncie Morning News (February 17, 1894) wrote:

"It seems to take all kinds of preachers for all kinds of men [...] there are some people who must have the sledge-hammer style of religious revivals, an dthere are others who wouldn't like anything but the plush and velvet style. There are tastes in religion, as in other things" (left).

This reporter described described preaching styles, but it is a short step to the physical experience of religion. Woodworth-Etter's tent church offered accessibility to all classes and races, but little in the way of "plush and velvet style." Perhaps her congregation chose spirit over space.

Muncie's diarists were equally divided over Woodworth-Etter's preaching style and church. In October 1886, the introspective widower Thomas Neely and his daughter Jennie witnessed her preaching. He wrote in his diary: "I think she is doing good work." In contrast the adolescent future engineer Thomas Ryan wrote in December 1886 that he disapproved of her congregation's "shouting, stamping and cutting all sorts of antics."

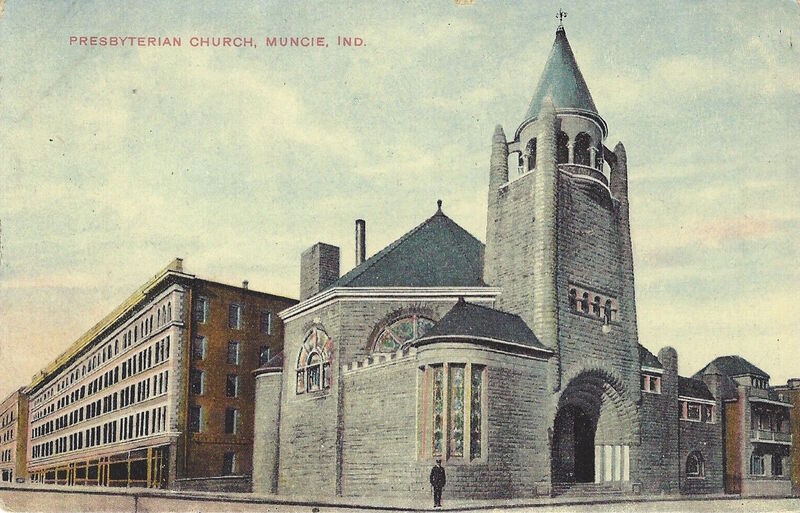

Perhaps Ryan was more impressed by the solid and staid religious experience of Muncie's older white Protestant churches. While they too were a hive of religiously directed activity, their presence in the center of town and their stone foundations projected a permanence at odds with revivals frenetic movement and transience. The postcard below showing Muncie's First Presbyterian Church is a good example.

Just as Muncie's religious buildings displayed various styles, so too did its religious communities. Although some newspapers and diarists disparaged Woodworth-Etter's work, others applauded. Perhaps more than tents and tabernacles, her forty-year preaching career is a fine testament to her skill and public interest.

To hear more about the historian's process and the methodologies used to research and create historical narratives, check out the conversation between Payton Glesing, Nikki Harmeyer, Jordan Sutton, and Caleb Woolace below:

Click on Anna Augusta Truitt to learn more about how Muncie's churches cultivated civic organizers. While Maria Woodworth-Etter was conducting her Indiana Blitz, Anna Augusta Truitt was working the the Women's Christian Temperance Union. Both venues offered woman a platform for values-based public speaking, and both were radical in different ways. See how Anna's work enshrined women as the protectors of Christian morality at the same time that Maria was attacked for her outspoken leadership.