Isabelle Prince Leon

Isabelle Prince Leon was born in 1844 in New Orleans and died in 1904 in Muncie. She was among Muncie's earliest Jewish settlers and lived here for forty years. Isabelle and her husband Frank cultivated a small but active religious community in a period before the construction of a synagogue. The couple also collaborated in business, running successful clothing stores in several Indiana towns as well as in Cincinnati. The expansion of the railways in this period allowed the Leons to keep a close watch on their businesses, as well as their family and friends across the Midwest.

This biographical video was researched and created by Kari Klem, Brenna Large, Alexis Slocum, and Genevieve McClure.

In his study of Muncie’s Jewish community, historian Dwight Hoover called Frank “the most spectacular example of Jewish integration into the life of the community in the nineteenth century.” This statement highlights the Leon family's success, while also obscuring Isabelle's own activities in business, religion, and society. On her death The Muncie Morning News called her “a well known woman,” which understates her impact and achievements.

The earliest histories of Muncie’s Jews focus exclusively on Jewish men. Alexander L. Shonfield’s history of the community, written in 1922, includes a series of short biographies of men that begins with Isabelle’s husband Frank (left). Women appear in this account only as wives, never as active congregants, business owners, or citizens. In contrast to this lop-sided account, contemporary newspapers reflected the importance of women in religion, business, social activities, and maintaining connections between friends and families.

Although Muncie's Jewish population was small, investigating Isabelle's life reveals how it cultivated religious community and also participated fully in public secular life. Shonfield notes that the earliest religious services took place in homes, in particular the Leon household in the city's commercial heart. While it is difficult to envision this, we know that women played a central role in preparing the home for the Sabbath (Shabbat) devotions: cleaning, preparing food, and welcoming guests. At sundown on Friday, as the woman of the house, Isabelle might have lit and blessed the Sabbath candles. At dinner, Frank as the man of the house, would have blessed the wine (kiddush) and Isabelle would have said the blessing over a special bread (challah). Perhaps they shared this weekly event with other Jewish families like the and celebrated in their homes on other weeks. On Saturday morning Frank and his sons might study and pray with men from the Herrmann, Wolf, Silverburg or Hart families. In the afternoon, there might be more study and pray, or rest and socializing.

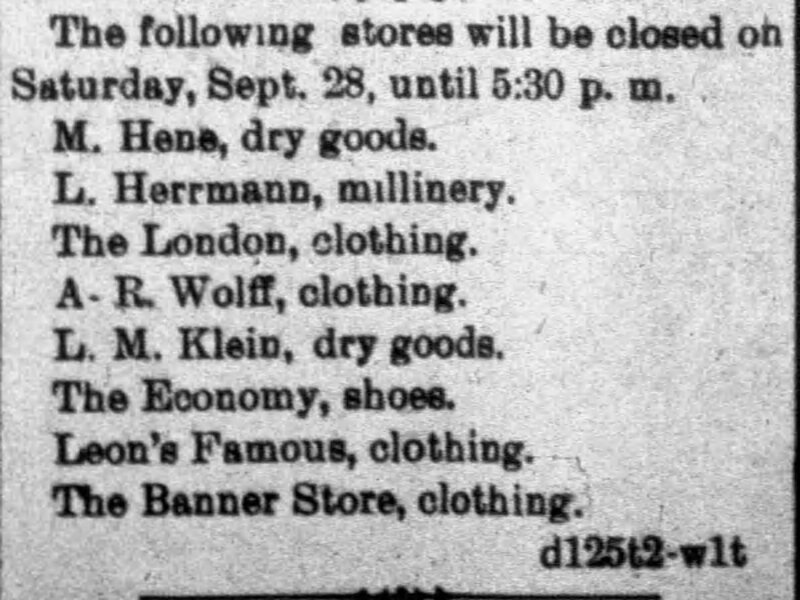

Above: notice of store closures from The Muncie Morning News, September 28, 1895. A similar announcement appeared in The Muncie Daily Herald on September 26, 1895. Neither notice identified the holiday by name.

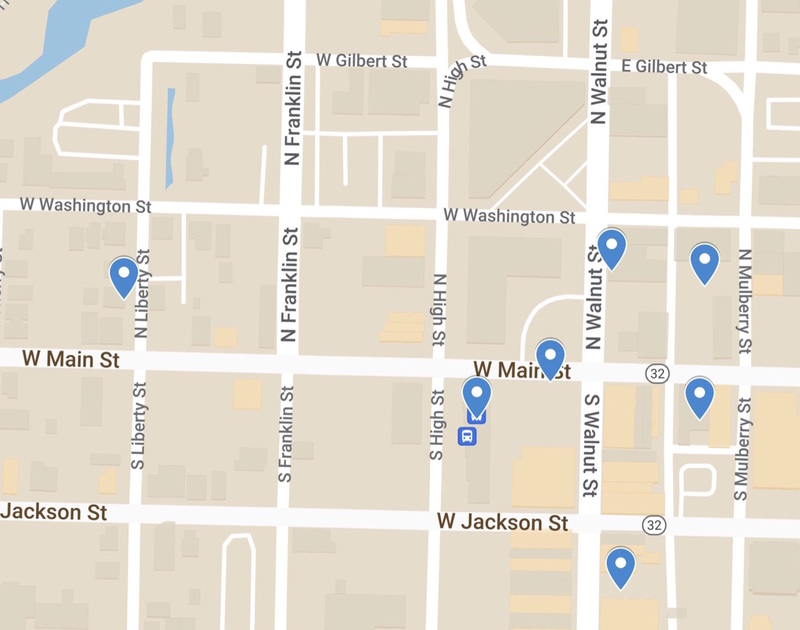

One way to see this devotion in public is through the closure of Jewish businesses for Yom Kippur, the day of atonement that ended the High Holidays. On the left is a newspaper announcement of business closures from 1895. By this time Isabelle and Frank had lived in Muncie for more than thirty years, and they were part of a well-known and well-liked Jewish community, but one that still had little knowledge of Judaism. The absence of an explanation for the closure suggests that Muncie's Christians would not have recognized the holiday's significance, and avoided the othering gesture of identifying Yom Kippur.

Historians of nineteenth-century America, like Hasia Diner, discuss the assimilation of Jews into American Christian societies at the same time that they identify how Jewish identity was preserved and displayed. The closure of Jewish businesses on Yom Kippur is one way to see that identity on Muncie's streets in late September 1895.

Left: a map of seven out of the eight businesses listed in the 1895 newspaper notice. The map uses addresses from the business listings in the 1893-94 Muncie City Directory.

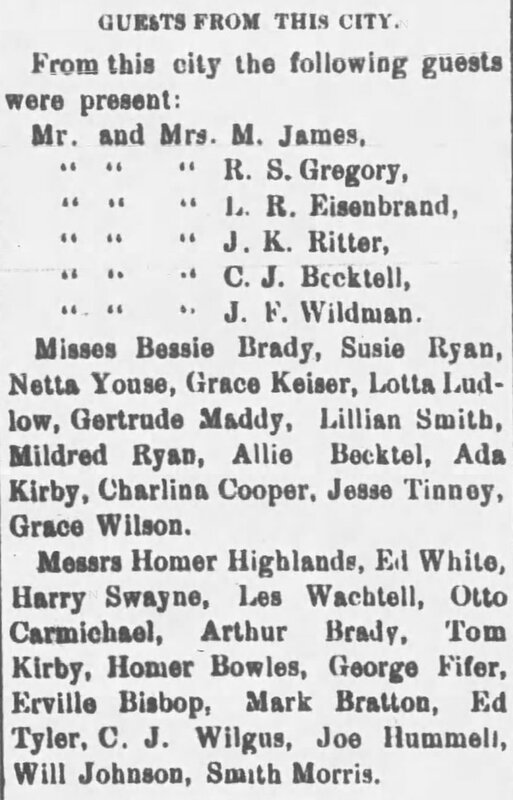

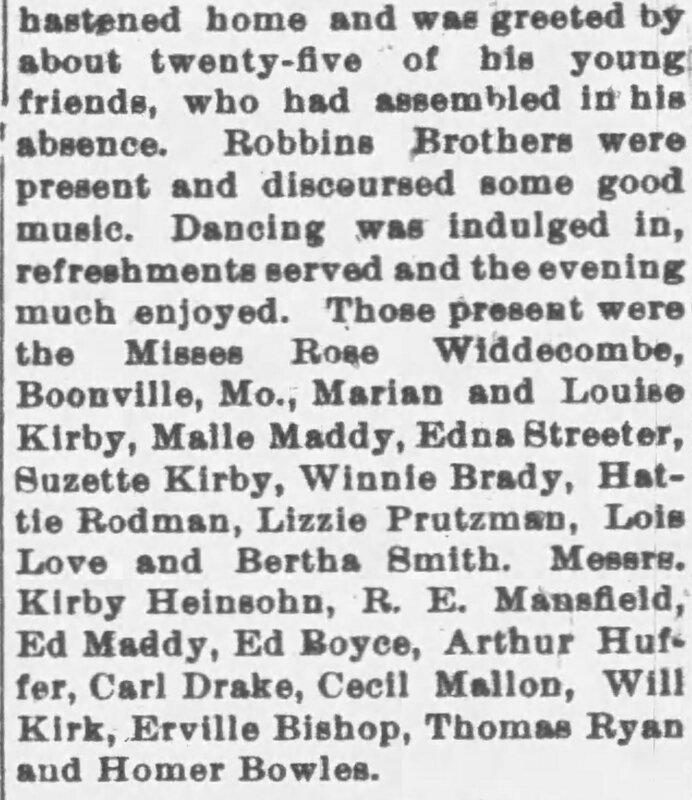

Of course, a thriving Jewish community did not mean that Isabelle and Frank only socialized with other Jews. When Isabelle and Frank threw a surprise twenty-first birthday party for their son Henry, the newspaper reported a guest list that was mostly Christian and probably included many of his former school friends. A similar list including youths from the city's important commercial and professional families appears in the account of the Kirby House reception celebrating their son Noddas and daughter-in-law's return from their honeymoon.

Left: detail of "The Leon Reception," The Muncie Morning News, July 21, 1887.

The events described above remind us of the balance that American Jewish families maintained in a period of great migration. Their lives were both Jewish and Munsonian, and involved celebrations that were religious and secular. Some friends were in only one of those groups, while others were both. Isabelle and her family's success in Muncie suggests that lack of knowledge about Judaism did not always lead to exclusion or antisemitism.

Left: detail of "Society Events," The Muncie Daily Times, October 9, 1891.

To hear more about the historian's process and the methodologies used to research and create historical narratives, check out the conversation between Kari Klem, Brenna Large, Alexis Slocum, and Genevieve McClure below.

Much as Isabelle Prince Leon's business activity is difficult but not impossible to discern, Belle Kelley's gender and her race produce intersectional challenges. As the female proprietor of the Pekin Hotel, documents often obscure or minimize Belle's contributions, and as a black hotellier, extant records are inconsistent. Click on Belle Kelley to learn more about Muncie's first black-owned hotel and its notable proprietor.