Introduction

In recent years, the popularity of women’s soccer has drastically increased in the United States. With the surge in popularity there has also been an increase in injuries, notably to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) (1). ACL injury typically requires surgery accompanied by a lengthy recovery. Following an ACL injury, the likelihood of re-injury and development of osteoarthritis are much higher (2,3). Soccer is a dynamic sport in which several movements putting the ACL at risk are regularly performed. Additionally, females appear to be at a higher risk than males due to extrinsic and sex-specific intrinsic factors. There appears to be a need to study the female soccer athlete’s risk of ACL injury in sport-specific movements.

ACL tears most often occur as non-contact injuries (4–7), which occur most frequently in soccer due to improper mechanics during jump landings as deceleration takes place (8,9). Extensive research has been done to better understand landing mechanics and the risks involved (10-17). Kinematic and kinetic mechanisms have been linked to ACL injury risk including deficiencies in hip and knee flexion (18-20), increased valgus angles and moments at the knee (21-24), high vertical ground reaction force (GRF) (22,25), and high anterior tibial shear forces (ASF) (7,26). Additionally, muscle activation patterns prior to, during, and immediately following initial contact have been recognized as potential factors, most notably poor quadriceps-hamstrings co-contraction (27).

In soccer, the primary motivation for field players to jump is to head the ball. Proper heading form requires the player to rotate the trunk to meet the ball where transferred forces then spring the trunk backwards (28). Studies have shown that landing from a jump with the trunk in a more upright position may lead to increased tibiofemoral joint loading (29,30), therefore landing mechanics following heading may be attributable to factors influencing ACL injury.

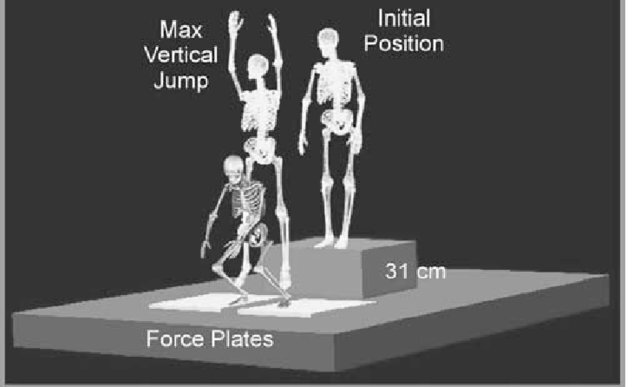

Studies have used the drop vertical jump (DVJ) task to analyze joint kinematics and kinetics as well as electromyography (EMG) patterns and their relationships with ACL injury mechanisms (19,31,32). Recently, researchers have begun to investigate not only the first landing of the DVJ, but the second landing as well (33,34). It has been concluded that the second landing of a DVJ displays characteristics of higher rigor athletic tasks than the first (34) and suggested that the second landing should be compared to the first to discover differences in how forces are mechanically absorbed (33). These DVJs were adapted to analyze landing from rebounds in basketball, however, no current research has adapted this jump to the soccer header. One study has analyzed biomechanical factors of landing from headers in conjunction with a stop jump, however, the study only considered the sagittal plane and no EMG was used (35).

The purpose of this study is to analyze the differences between landings in 3-D lower extremity kinematics and kinetics, GRF’s and muscle activation patterns in female soccer athletes to better assess the risk for ACL injury in header landings. It is hypothesized that lower extremity biomechanics associated with ACL injury risk will emerge from the header landings when compared to DVJ’s. More specifically, less knee flexion upon landing, higher GRF’s, increased external knee abduction moment, and poor quadriceps-hamstrings co-contraction.