Cornelia Frazier

Cornelia Frazier was born around 1873 and died in 1897. Her short life left few traces. This reflects the situation of many other members of the working class, who lived before the 1930s when American states standardized the recording of births and deaths. Most wage laborers did not own property or leave wills, which reduces even further their remaining documentary traces. This poses a great challenge to historians, who seek to understand lives that were ordinary, but which involved experiences shared by millions of people.

This biographical video was researched and created by Grace Benedict, Jalen Chandler, Brady Killion, and Ryan Melbert.

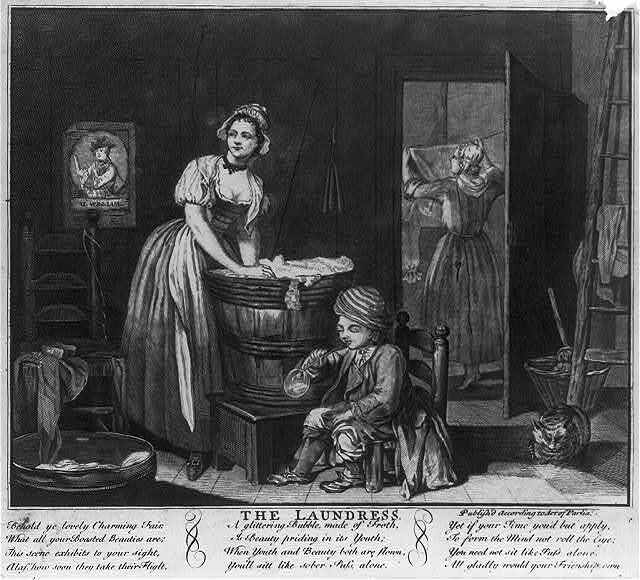

When we think about laundresses, we might consider sheets waving in the wind on a laundry line or a maid (like the one above) bending over a tub of sudsy water. This image (above) is a deceptively romantic vision of laundry and the laundress' life. To the modern eye she appears young and attractive, and longs for the better-dressed beau pictured on the left. The verses below the engraving suggest that her beauty and hope for escape from this work are fleeting, just as a soap bubble might be popped.

In reality, washing laundry was monotonous, unending, back-breaking labor, that was essential even as it was outsourced by white-collar and upper-class households. As tenements crowded Chicago and New York's working-class neighborhoods, and laundry lines strung between windows, few white-collar or professional families wanted to be associated with this chore or the tenement dwellers, Chinese immigrants, and other impoverished Americans who did the work.

Not surprisingly, we know very little of Cornelia Frazier's life as a laundress. While we can learn a great deal about laundries, mechanized washing machines, and the gendering or ethnic tags associated with hanging laundry, the lives of individual professional laundresses are mostly lost. The famous laundress, Sarah Breedlove, turned hair-care entrepreneur, Madame C.J. Walker (below), is a good example. But if it were not for her success as America's first self-made female millionaire, we would know less about the harsh chemical-filled life of the laundress.

But as the video biography (above) tells us, Cornelia Frazier did not become a millionaire. She worked as a laundress in Muncie's most prestigious hotel and died at the age of 23. With so few records and no first-person account of her life, how do historians proceed? To understand her life, historians must explore what she is known to have experienced, rather than her own reflections. This requires us to consider the place of laundry work, hotels, and religious revivals or camp meetings in late nineteenth-century society.

For a moment let's consider whether Cornelia's race was connected to her profession. A search of the city directory in 1893-94, identifies several commercial laundries in Muncie, including Cottage Steam Laundry, Muncie Steam Laundry, and New Era Steam Laundry. Almost all of their employees were white women.

At the New Southern Hotel, on 607 South Walnut Street, both the "laundry girls" were white and boarded at the hotel, just like the Frazier sisters. One of them, Minnie Stall, lived with her sister, Sadie, who worked there as a waitress. The same city directory reveals that the Kirby House Hotel, where Cornelia worked from 1893-97, offered accommodation to both white and black staff. Alongside the Frazier sisters, Mamie C. Shea (another laundry girl), Gertie Johnson (waitress), and Julia Fifer (dishwasher) lived and worked on the premises. However, Mrs. Antoinette Stillwag, the married laundress at Muncie's National Hotel, lived elsewhere. This suggests that for unmarried working-class women, on-site accommodation could be a perk of employment.

Similarly, Miss Samantha Moore, the Blount House Hotel's second cook, lived where she worked. At the National Hotel, also in Muncie, the second cook, James Stewart also boarded there. Both employees were white, but likely of greater importance that laundry girls in the hotel hierarchy. Knowing this about hotel employees across the city, we cannot assume that Cornelia's race limited her to laundry work or to living where she worked.

Cornelia's life reminds us that the white-collar or professional model of life is only one version of the past, which had little impact on her as a working-class woman. She lived with her sisters at their place of work, rather than with their parents in a family home. She attended revivals and camp meetings, rather than the women's clubs that formed at Muncie's larger churches. Her early death from tuberculosis seems to have kept her from marriage, children, and a household of her own. Aspects of Cornelia's life were not unusual, even if they diverge from the white-collar professional model. This poses a welcome challenge to historians to find and reflect on similarly important, but lightly documented lives.

To hear more about the historian's process and the methodologies used to research and create historical narratives, check out the conversation between Benedict, Chandler, Killion and Melbert below.

This biographical video (far above) places Cornelia, and other laundresses who worked in Muncie and elsewhere, at the center of economic structures that depended on their labor, but catered to wealthier clients. Although the laundry was being transformed by technological change, Cornelia's labor was considered unskilled and likely paid poorly.

Click on Lee See Chin to learn more about how the laundry business changed over time. Not only does it tell us about how immigrant stereotypes gendered laundry work, but it shows how immigrant groups evolved and moved through different professions.