Mabel Keuchmann Snider

Mabel Keuchmann Snider was born in Indiana in 1873. Her parents, Matthias and Elmira/Myra Keuchmann were German immigrants, who had settled in Muncie by 1879. The family ran a music store selling a wide variety of instruments and sheet music, and were active members of "Muncie's musical set."

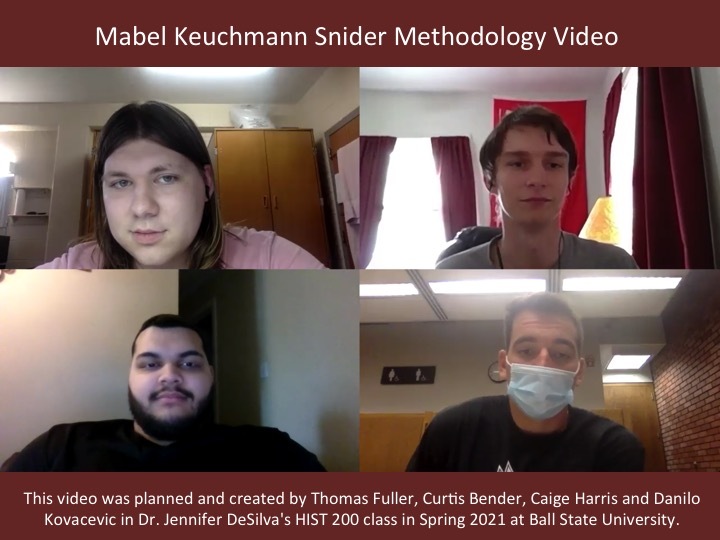

This biographical video was researched and created by Thomas Fuller, Curtis Bender, Caige Harris, and Danilo Kovacevic.

As the video biography and the newspaper clipping above show, Mabel and her family were active members of Muncie's musical community. While the ability to sing and play an instrument was generally considered to be an appropriate female accomplishment, Mabel and her sisters, Abbie/Abelyn and Katharine, went far beyond this expectation.

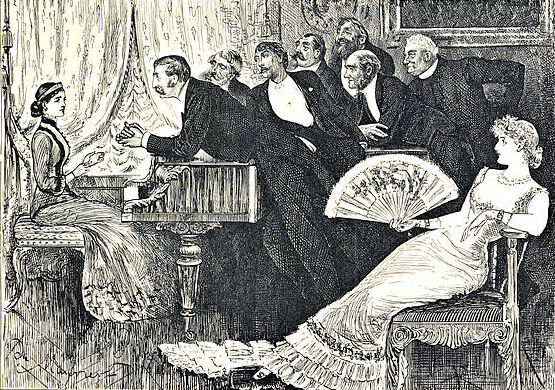

Both Mabel and Katharine trained at a conservatory in New York City. Mabel trained with English concert pianist, composer, and teacher Sebastian Bach Mills. His concerts in New York helped to popularize piano concerti by Beethoven, Schumann, Liszt, and Chopin. On Mabel's return to Muncie in 1892, she and her sister Abbie gave a variety of public concerts, both locally and further afield. The two sisters, a pianist and a violinist, formed a professional company with Eugene W. Douglass, an actor and elocutionist, who worked at the Metropolitan School of Music in Indianapolis. This partnership took the women far beyond the traditional model of parlour-based amateur performance seen in the illustration below.

In the nineteenth century, playing the piano was considered a feminine past time as it was associated with beauty, the home, and leisure. A white-collar or middle-class father might hope to purchase a piano and pay for lessons for his daughters, as a sign of his economic achievement and their social status. He might encourage his daughters to learn to sing and accompany each other on the piano as "elegant accomplishments," in the words of Mrs. Lanfear, the author of Letters to Young Ladies on their Entrance into the World (1824). Such skills would not help the women run a household, but they might attract admirers of similar class, wealth and culture, as the print below suggests.

Paid public performances threatened to transcend the respectable amateur model that was expected of middle-class women. Most nineteenth-century depictions of women playing the piano include other women singing, a few male spectators, or children. Very few women became professional pianists or made a living from public concerts. For all but a select few women, like Clara Schumann, the nineteenth-century stage was the opposite of respectability. Generally, once women married, "elegant accomplishments" like playing the piano would be laid aside until they could be taught to one's own children.

Sadly, this appears to have been Mabel Keuchmann and her sisters' experience. Muncie's clubs, like the Matinee Musicale and the Women's Club, offered some public performace opportunities, but they were hardly on the same scale as Mabel's New York training had prepared her for. Contemporaries applauded women's musical skill in local venues and at amateur benefit concerts, but there were few professional opportunities for most musical women beyond teaching.

To hear more about the historian’s process and the methodologies used to research and create historical narratives, check out the discussion with Fuller, Bender, Harris, and Kovacevic below.

Although women's education and legal equality expanded from the nineteenth through the twentieth centuries, being a wife and mother remained at the core of the public expectation of women. Paradoxically, the ideology of maternalism allowed women from privileged social and economic backgrounds to leverage their positions as mothers to implement wide-reaching social programs in their cities. Click on Mrs. M.C. Smith to consider how maternalism brought opportunities for some female leaders to work outside the home.