Lee See Chin

Lee See Chin's lifetime spans important changes in the Chinese immigrant's experience in America. Born in China in 1905, Lee Shee Chin was 17 when she married Lloyd Chin and arrived in the United States. The couple lived briefly in Chicago and moved to Muncie in 1923, where they resided until their deaths in 1954 and 1945 respectively. During this time legislation loosened, allowing more immigrants to arrive from China, and new work opportunities signalled a slow acceptance of Asian-Americans.

This video was researched and created by Kenny Deetz, Nadia Dobrzeniecki, Parker Harrington, Kyle Lowden, and Zachary Palmer.

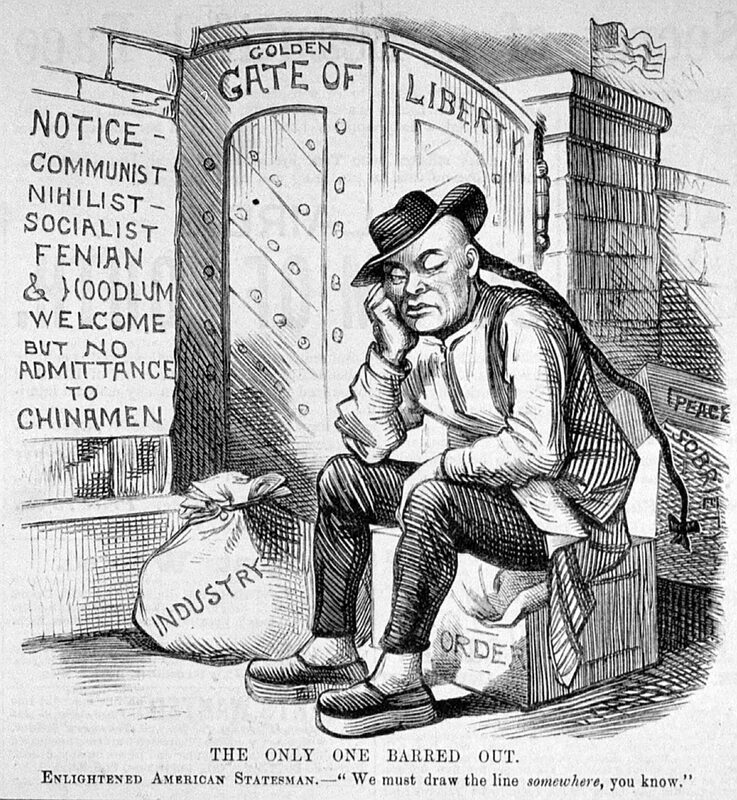

From the 1850s, Chinese men traveled to the United States to work in low-skilled positions building the railways, mining for gold, farming, and in the garment industry. A series of treaties signed between China and the USA in 1858 and 1868 eased immigration and allowed more than 300,000 Asian people to enter the country before 1882. Undoubtedly, the period of 1870 to 1920 marked rise of Asian immigration to the United States, but the low-cost labor provided by Asian immigrants prompted a backlash from native-born Americans and other non-Asian immigrant groups. The cartoon below illustrates the popular vision of Asian immigrants in around 1882: a male worker, wearing a queue/braid, and without a wife or family.

The cartoon above shows the situation in 1882, when the American government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which stemmed the tide of immigrants. This legislation prohibited "skilled and unskilled" Chinese immigrants from entering the United States or applying for citizenship. Congress renewed the act in 1892 and then extended it indefinitely, until 1943 when all exclusion acts were repealed.

Unlike the millions of European immigrants arriving at that time, only a small number of Chinese merchants received permission to emigrate, and later bring their wives. The cost of travel and the limited work opportunities for Chinese women meant that in 1855, women made up only 2% of the Chinese population in the United States, and in 1890 this had only risen to 4.8%.

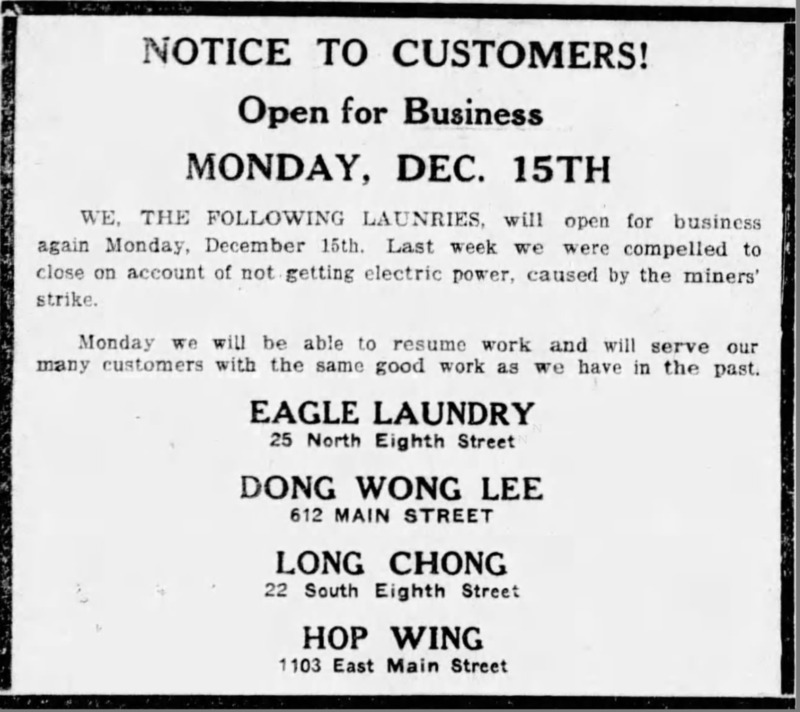

For Midwesterners, between 1870 and 1920, Asian workers were most often seen in what became known as "Chinese" laundries. In 1874-5 Chicago had 18 Chinese laundries and 2 of Indianapolis' 4 laundries were under Chinese management. As the video biography explains, these were businesses that could incorporate family members and offered some protection from anti-Asian prejudice and exploitation.

The advertisement shown here (left) advertises four Chinese laundries in Richmond, Indiana. In 1919, Richmond had c.26,000 residents, which suggests that as the population grew small cities attracted a more diverse mix of residents and were willing to support more migrant-owned businesses.

In the sketch below, it is tricky to discern whether the second figure from the left is male or female. In the 1870s Chinese men who intended to return to China were expected to maintain their queue/braid, as a sign of loyalty to the Manchu Qing emperor. While the viewer cannot see a braid on that figure, it does not indicate a woman with absolute certainty. If that figure is a woman working in a laundry, likely depicted alongside her husband, she would be a rare example of female from the 1870s.

In time the slowly growing Asian-American population shifted from the laundry business to running restaurants offering both Asian and American food. This development signals a growing community that needed an inexpensive source of prepared food that doubled as a social center. Much like in laundries, in family-run restaurants, women could work either in the kitchen with other staff or in the dining area with customers, allowing some flexibility.

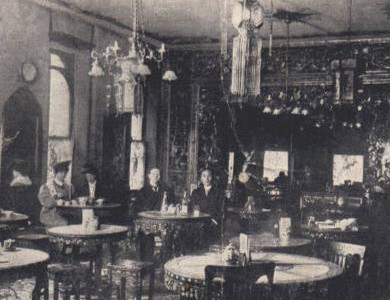

However, in the early 1900s in larger cities like Chicago, eating at upscale Chinese restaurants became a fashionable and exotic outing. To encourage non-Chinese customers, many restaurants served both Chinese and American dishes. Below are photographs of sample restaurants in Chicago and Indianapolis. The continued increase in Chinese restaurants through the twentieth century reflects the spread of Asian-Americans across the country and the acceptance of Chinese cuisine and culture in American society.

To hear more about the historian's process and the methodologies used to research and create historical narratives, check out the discussion with Deetz, Dobrzeniecki, Harrington, Lowden and Palmer below.

Click on Sallie Harris Herrman to learn how she strove to establish herself as a businesswoman and a social organizer in Muncie. Although Sallie was not an immigrant, nineteenth-century newspapers described the arrival and increase of Jewish immigrants in a way that combined Jewish citizens and immigrants together.