Ruby Leota McCray

Ruby Leota Browner McCray was born in 1893 in Indianapolis. Before 1915 she and her siblings had moved to Muncie. There she married Ebenezer (Ebbie) McCray and gave birth to a son, Fred. The couple filed for divorce in late 1915. Soon after her divorce, Ruby Leota McCray had a relationship with Frank Bass, first as his housekeeper and then as his common-law wife. Following his death and her imprisonment, in 1926 she married Silas McMath. As local newspapers reported, their union also ended in divorce.

In her relationships, Ruby was hardly different from many other women at this time. Demographers have argued that in the early twentieth century the US census over-reported widowhood among African-American women. Analyzing data from the 1910 decennial census, Preston, Lim and Morgan found that "marital turnover was faster than can be explained by actual widowhood or formal divorce" and that "marriage was more fluid" for African-American women. These conclusions help us understand aspects of Ruby Leota Browner McCray's life, but more research into Muncie's divorce rate (and the black and white divorce rate) in this period would offer greater local context about women's work and economic stability.

This fluidity of intimate relationships surely had an economic impact on Ruby Leota McCray's working life. There is no evidence that she was a skilled worker. City directories list her as Ebenezer McCray's wife (without an occupation) and in 1921 she described herself as initially employed by Bass as a housekeeper. While running a household involved a portfolio of essential skills, they were undervalued and poorly paid when contracted out. Ruby's transition from Frank Bass' housekeeper to common-law wife is one example of the perils that women might face.

This biographical video was researched and created by Nathan Earle, Chase Eggeman, and Grant A. Wilson.

Black and Blue: Ruby Leota McCray and the Struggles of Black Women in Muncie's Red-light District

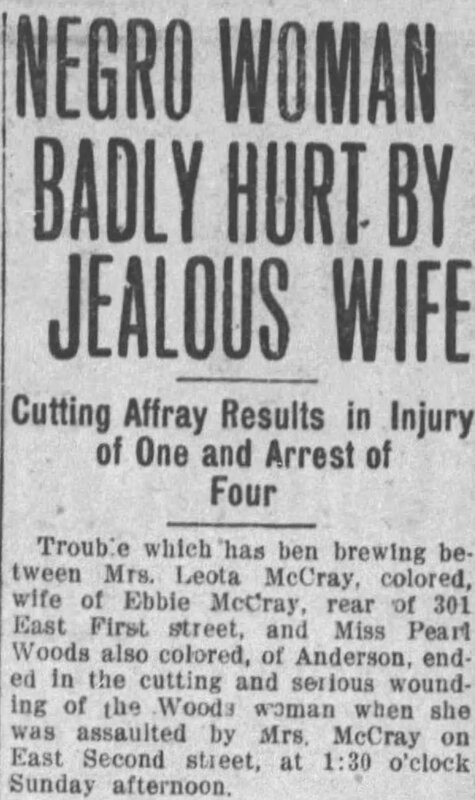

Indeed, as this video indicates, Ruby encountered violence as both victim and perpetrator. The newspaper article (left) reports her attacking a woman who had drawn her first husband's attention, only months before they sought a divorce.

As the Carrie Gillenwaters project in Town On Fire 2020 reported, in the 1870-1920 period newspapers reported many violent incidents related to African American women. Paradoxically, there were long-lived stereotypes describing black women as victims of abuse at the hands of violent black men and as over-bearing and violent themselves. As the biography video (above) notes, stereotypes about black men being violent and sexually brutish supported white fears of black violence, and could reinforce lies that resulted in unjust black deaths.

One of the challenges of narrating Ruby Leota McCray's life is related to using these same newspapers as a central source. The old editor's saying "If it bleeds, it leads" results in having many records of violent altercations, arrests, and fines, and fewer reports of proud achievements celebrated by the community. (Newspapers also listed applications for marriage licenses and divorces.) Dangerously, this imbalance in sources can lead historians to wonder if violent episodes or shifting domestic arrangements characterized an entire life. That situation requires historians to read silences and test hypotheses with whatever sources that remain.

In considering Ruby Leota McCray's six-year connection to Frank Bass, the question arose of whether she worked only as a housekeeper or participated in his illegal activities. Without evidence, we cannot assume that she did. However, by building a picture of her community, we can infer her larger knowledge of illegal liquor sales in the years that she lived in Muncie. This exercise also tests the connection between race, gender, and this type of illegal work.

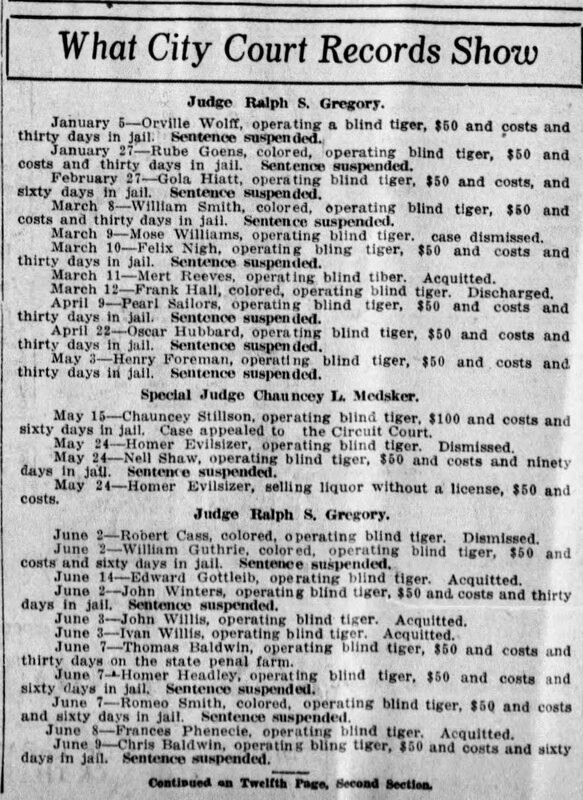

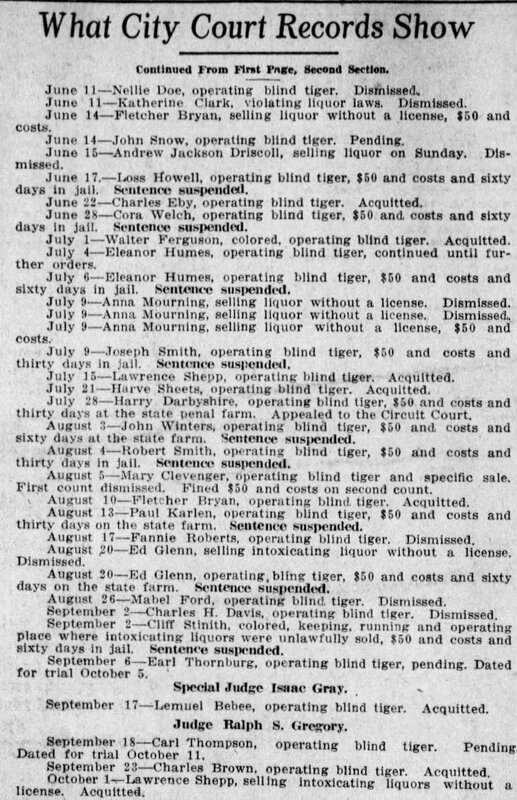

Below are two newspaper clippings listing people arrested for illegal liquor provision in Muncie from January 1st to October 1st, 1915. By checking the 1913-14 city directory for each name, the person's race, and household address, it became clear that in Ruby lived in a neighborhood full of opportunities to purchase alcohol illegally from both black and white sellers.

"What City Court Records Show," The Star Press (October 3, 1915).

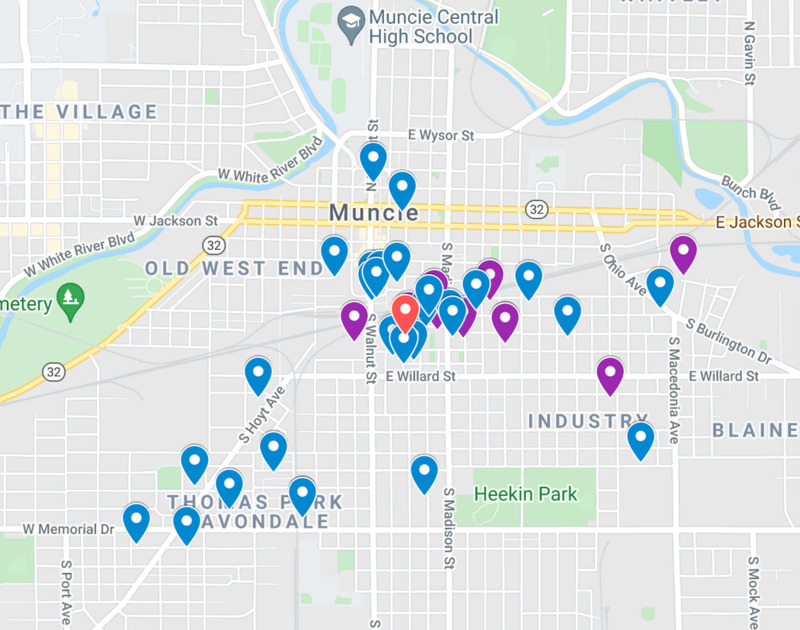

Map showing households (or locations of arrest) for 45 out of 60 arrests (made January 1st to October 1st, 1915. Purple pins are black households. Blue pins are white households. Red pin is Ruby Leota McCray's home. (Some households were arrested twice in this period.)

In 1915, according to that year's city directory, Muncie's population was approximately 33,975 people, with 4.4% black and 95.6% white. The city's racial composition suggests that black people were over-represented in this list of arrests, with around 21.7% of arrests in this list (13-14 out of 60 arrests). Given how many arrests there were in this short period in Ruby's neighborhood, it seems impossible that she not have some knowledge of the local activity. Also, given how close together black and white households were and how many arrests there were from each racial group, it was clearly not a segregated community or a racially-exclusive crime. But so far, there is no evidence that Ruby worked in any of Frank Bass' illegal operations.

While this test brings us a bit closer to understanding Ruby's neighborhood, it also complicates our understanding of Muncie's past. Illegal alcohol was a booming business that involved women (15 arrests or 25%) as well as men, and black as well as white workers, but it extracted a great price. Fines, jail time, social disruption, and violence cluster around this group. There is still a great deal to learn about how this type of work affected Monsonians, and tests like these prevent drawing unfounded conclusions.

To hear more about the historian’s process and the methodologies used to research and create historical narratives, check out the discussion with Earle, Eggeman, and Wilson below.

Black and Blue: Ruby Leota McCray and the Struggles of Black Women: Methodology Video

Click on Conclusion to reflect on what these six lives tell us about working women in Muncie from 1870 to 1920.