Sallie Harris Herrmann

Sallie Harris Herrmann was born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1860 to Polish and Prussian immigrants. In 1876 she married another Prussian immigrant, Leopold Herrman. Her Jewish faith is an important aspect of her life as a white-collar business owner and clubwoman. Not only was nineteenth-century Muncie a city of racial and ethnic diversity, but it also reflected the religious diversity (albeit on a smaller scale) that was found in larger cities like Chicago and Indianapolis.

This video was researched and created by Russell Baas, Maggie Jones, Shelby King, and Tim Slatton.

Through the nineteenth century Jewish immigration to the United States of America increased dramatically as persecution in Eastern Europe rose. Louisville had attracted Jewish migrants from the very late 1700s, and in 1880 Louisville's Jewish population numbered around 2,500 people. Sallie's family joined a community populated by entrepreneurs, and industrial and commercial laborers, which mirrored the character of other Midwestern Jewish communities. In 1895 the Big Four Railway connected Louisville with Indianapolis and other cities boasting larger Jewish communities. From Louisville Sallie could travel to Cincinnati, which had a Jewish population of 15,000 in 1900, and to Chicago, which had a Jewish population that grew from 10,000 to 225,000 between 1880 and 1930.

The railway map below shows how Sallie and other travelers could move between big cities like Chicago, medium cities like Louisville and Cincinnati, and small cities like Muncie, with ease in the 1880s and 1890s CE. The red dots on the map identify (west to east) Saint Louis, Chicago, Indianapolis, Louisville, Muncie, and Cincinnati.

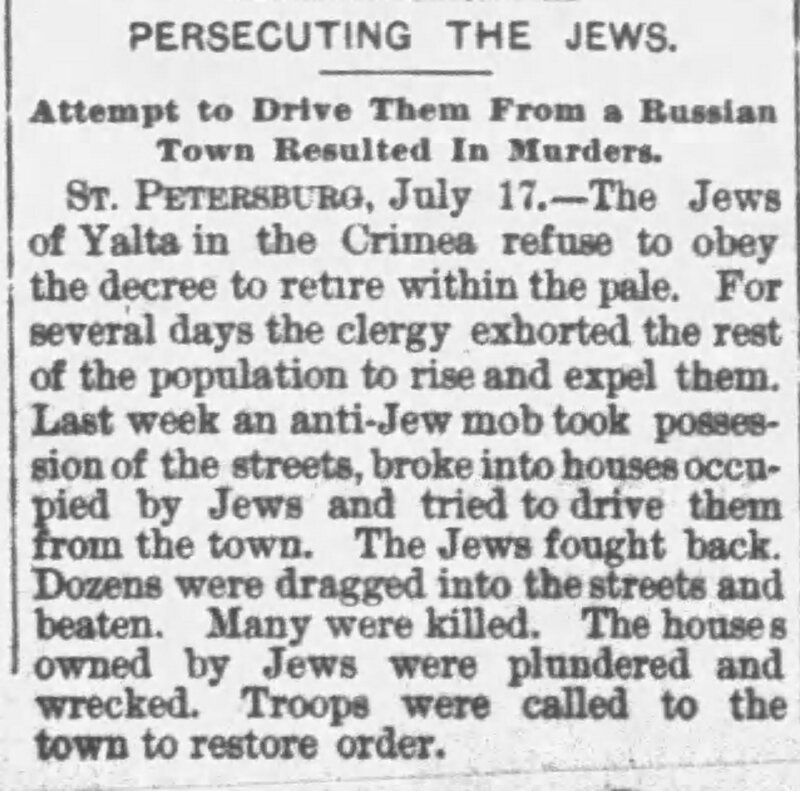

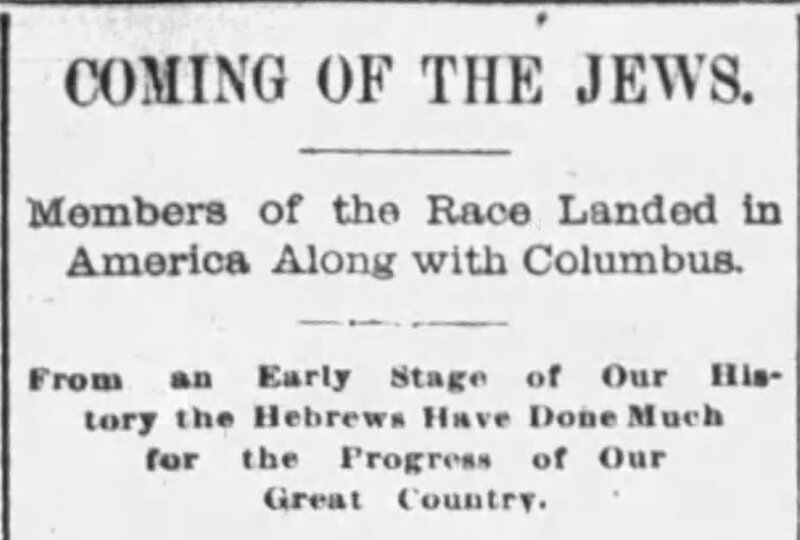

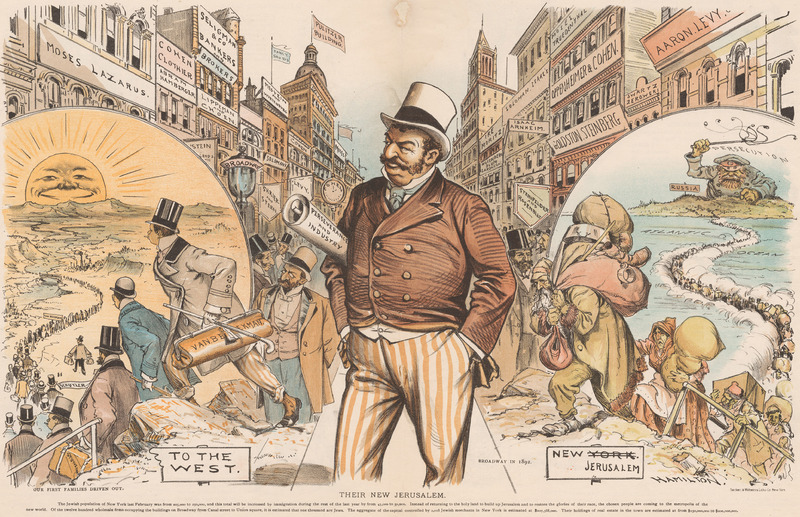

In the late nineteenth century, Jews in Eastern Europe and Russia were increasingly under threat. American newspapers printed both skeptical and sympathetic accounts of this violence, at the same time that cartoons appeared characterizing Jewish immigrants as hardworking, successful, and invidious. These sources present an ambivalent relationship between Christian newspapers (and their readers) and American Jewish communities. Many newspaper articles described the perceived links between American and global Jewish communities, repeating old stereotypes that depicted Jews variously as a vulnerable group and as a great immigrant success story. The cartoon below illustrates the stereotypical perception of transformation that living in New York had on Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe and Russia. Notably, the cartoon depicts Jewish success as displacing older, well-established Christian families.

Grant E. Hamilton, "Their New Jerusalem," Judge Magazine (1892).

"The Jewish population of New York last February was from 225,000 to 250,000, and this total will be increased by immigration during the rest of the last year by from 45,000 to 50,000. Instead of returning to the holy land to build up Jerusalem and to build up the glories of their race, the chosen people are coming to the metropolis of the new world. ..."

In 1890, Sallie and her husband Leopold moved to Muncie and opened a millinery and fancy goods shop, where she also apprenticed hairdressers. Whereas Louisville would see five more synagogues founded before 1905, Muncie's Jewish congregation was substantially smaller. Because it never numbered more than 200 people (in a population of 15-20,000 people), it struggled to build a synagogue and employ a full-time, resident rabbi. As president of the Jewish Ladies Aid Society in the late 1890s, Sallie's work often focused on fundraising through social events.

Notwithstanding some social prejudice, Muncie’s Christian population seems to have been interested in its Jewish neighbors, and once again the newspapers offered guidance. The articles below show what information newspaper readers encountered about Jews and Judaism, alongside notices about the events organized by the Jewish Ladies Aid Society.

While the newspaper articles above suggest a public interest in learning about the Jewish community and its history, they also portray Jews as a race or a group set apart from the rest of American society. Depicting American Jewish communities as a monolith or as an encroaching global network moved it closer to the worst stereotypes of this period. In practice, diversity was difficult, even as different racial and religious groups learned more about each other.

To hear more about the historian’s process and the methodologies used to research and create historical narratives, check out the discussion with Baas, Jones, King, and Slatton below.

Click on Mabel Keuchmann Snider to think about a different sort of working women. In the late nineteenth century when German composers were popular, music allowed Mabel to keep in touch with her immigrant parents' German roots. As a concert pianist, Mabel's skilled work was more socially admired than a milliner or hairdresser, even as it paid less money. Indeed, earning money from public performances was problematic for white-collar women.