Julia Sparr Coffin

Many of the Town On Fire videos have explored examples of immigration or migration to Muncie. In the late nineteenth century, Muncie and the Midwest generally benefitted from the arrival of millions of people seeking work. While most immigrants to the Midwest were Europeans, thousands of White migrants and hundreds of Black migrants journeyed to Muncie seeking work. The Nuns of St. Lawrence School came from Canada, across the Midwest, and Europe. Mabel Keuchmann Snider's parents came to Muncie from Germany. Isabelle Prince Leon's husband came from Lorraine, France. Carrie Gillenwaters and her family migrated from Kentucky, while Maggie Morin and her husband came from Ohio.

Fewer people came from Asia, especially after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. Most Chinese men who did travel to work in the United States lived in larger cities than Muncie or on the West coast. Only in 1923 did Lee See Chin, who immigrated with her husband from China, arrive Muncie. Yet decades before her arrival, Munsonians were already thinking about women in China. Julia Sparr Coffin's work as a Methodist missionary and pharmacist in the southeastern city of Fuzhou encouraged the city to think more about about distant places.

This biography video was researched and created by Olivia Baskerville, Isaiah Martin, Joseph Martindale, and Rhian Mehlbauer.

In the 1870s and 1880s in Muncie's newspapers, China appeared most often as tableware, alongside glass and cutlery. Munsonians knew of China, but considered Chinese immigration to be a problem for California. Chicago and Indianapolis both had small Chinese communities before 1900, but no from Asia lived in Muncie until a Chinese laundry opened around 1904.

Julia Sparr's decision in 1879 to join the Women's Foreign Missionary Society of the Methodist Church turned Muncie's attention definitively towards China. Founded in 1869, the Society raised money to send women to serve in already established Methodist missions. The Society had a particular interest in Asia and in women with medical training.

Above: The Muncie Morning News (November 5, 1879).

Above: The Muncie Morning News (May 7, 1879).

Above: The Muncie Morning News (March 31, 1884).

Above: The Muncie Morning News (December 21, 1894).

Through the 1870s and 1880s, other Methodist denominations followed the Episcopal model, establishing their own missionary societies. The expansion of communications routes in this period meant that more people could travel as missionaries, and publicize their experiences once they returned home.

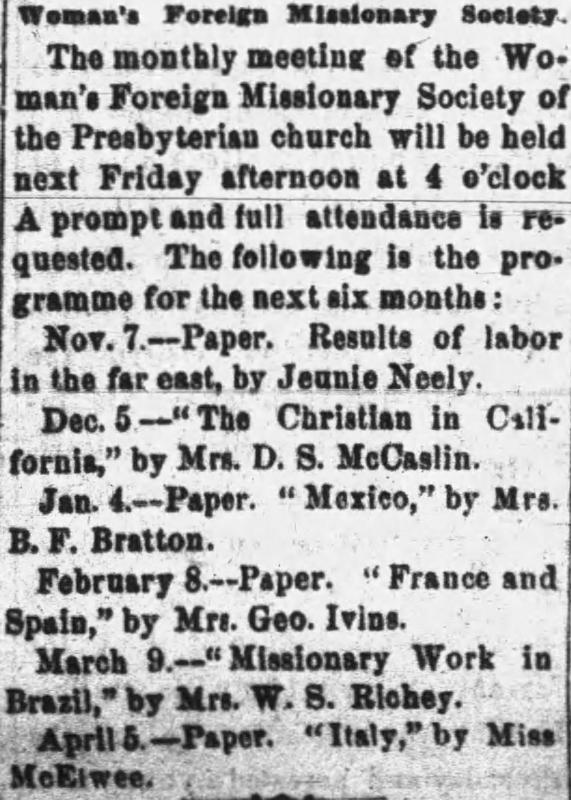

Muncie hosted missionary society chapters in both the Methodist and Presbyterian churches. Like other church groups, they attracted mostly female members. The newspaper article (right) lists the monthly schedule of discussions for the Presbyterian society 1879-80. Most women who joined these societies had no intention of leaving home. Nevertheless, they supported their goals through fundraising and attended their public lectures.

The daughters of Reverend James Sparr were no mere observers. In the 1840s their father had been a traveling pastor in northern Indiana. By 1870 he had married and settled in Muncie, where he built cisterns, in addition to preaching. Julia and her sisters Belle and Emma all participated in the Methodist society. Although Julia was the only woman to become a missionary, her sisters and mother Rachael were active Women's Foreign Missionary Society members.

From 1879 to 1884 when Julia was in China, while her family supported the Society's work in Muncie. In May 1879 a newspaper article announced that 21-year-old Belle had been to Indianapolis to attend a missionary convention. A few months later, Belle made a presentation at a monthly society meeting. In March 1881, Belle gave a paper at the Missionary Tea, hosted by Mrs Hasty with twenty-five other women. She spoke about "Bulgaria and Its Religions" and the newspaper called her one of Muncie's leading literary characters. While her sister Julia was away, Belle maintained the family's position in Muncie's missionary society.

After completing medical school, Julia Sparr accepted a missionary-doctor position in Fuzhou, the capital of China's Fujian province. At Fuzhou, she worked alongside another female doctor, Sigourney Trask, who had arrived in 1875. Trask oversaw the building of a hospital in Fuzhou, which served women of all classes. When Julia Sparr arrived in 1879, she took over the dispensary that served out-patients. In 1884 after five years in Fuzhou, she returned to Muncie to marry Auguste Coffin, a tea merchant. They quickly returned to China, but not before she shared her knowledge of China with 450 people at the Methodist Sunday school. A week later she gave another lecture after services the Simpson Chapel.

Sadly, when Julia Sparr left Muncie, so did much of the city's first-hand knowledge of China. Although Sparr and Trask had often used an interpreter to communicate with patients, their experiences living and working in Fuzhou were vastly different from life in Muncie. After her wedding, Sparr returned to China with Coffin where they lived until 1890. Several years later in 1894, Sparr gave another lecture at Muncie's Methodist Episcopal Church, entitled "The Middle Kingdom and Homeward."

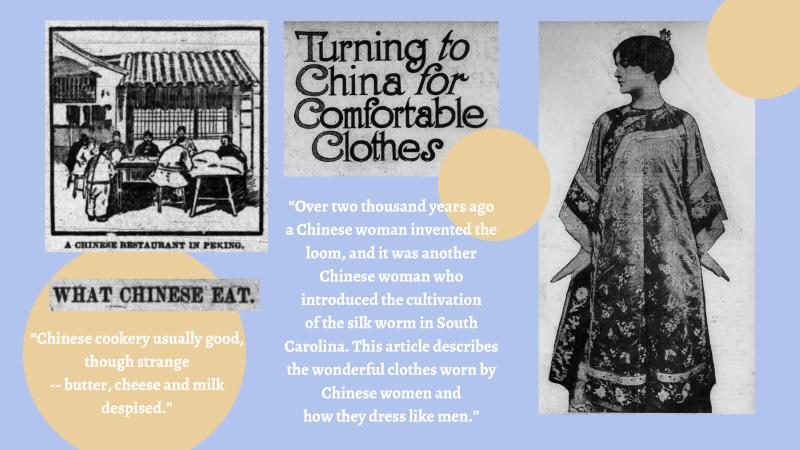

After 1894, Muncie chiefly learned about China through newspaper articles reprinted from larger city newspapers. As Asian immigrant communities increased in size across the United States, readers encountered more articles about Chinese culture and practices. As the excerpts below show, American enthusiasm for learning about China did not entirely replace its xenophobia.

To find out about the research behind this project and the twists and turns that it took, watch this methodology video created by Olivia Baskerville, Isaiah Martin, Joseph Martindale, and Rhian Mehlbauer.

While little was reported in Muncie's newspapers about Julia Sparr's medical practice in Fuzhou, click on Ellen Taylor to explore an abortion case that made headlines.